There is a growing consensus among economists that the U.S. economy is now heading into a recession. Despite this, the Federal Reserve held out at its latest policy meeting at the end of July and decided to keep its policy-setting funds rate unchanged at 5.33%

One day after the Fed announced its decision, the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee, MPC, voted to cut its bank rate from 5.25% to 5%. The decision was narrow, with five MPC members favoring the cut and four opposing it, but it was a rate cut all the same.

The Bank of England is not the anomaly here. It is following a trend of central bank rate cuts. The Swedish Riksbank cut its policy rate from 4% to 3.75% back in May. In June, The Swiss National Bank made a 0.25-percentage point cut and the Danish central bank lowered its leading policy rates from 3.6% to 3.35%. On July 24th, Hungary’s Magyar Nemzeti Bank reduced its policy rate from 7% to 6.75%.

While the smaller central banks around the euro zone are cutting their rates, the European Central Bank decided back in July to keep its three policy-setting rates unchanged. The general reaction was one of surprise, given that the EU economy is standing still and beaming out signals that it is going absolutely nowhere, except into a recession.

The problem for the ECB is that it is reluctant to act when the European economy needs it to act—unless the U.S. central bank, the Federal Reserve, is moving in the same direction. This dependency on the Fed has evolved gradually over the ECB’s 25-year history, and it shows no signs of abating.

With that said, we can expect both the Federal Reserve and the ECB to make cuts in September. The Fed meets September 17th-18th, while the ECB’s Governing Council holds its next meeting on September 12th. The ECB will make its cuts in anticipation of the Fed lowering its funds rate a few days later.

While the Fed is unlikely to take any other central bank into account when making its decisions, it is under market pressure to make a funds-rate cut in September. This is vividly visible in the market for U.S. Treasury securities; in the past week, yields have fallen on almost all of the different bills, notes, and bonds that the Treasury sells. The declines were most pronounced on Treasury notes, which mature in 2-7 years; from Monday, July 29th, to Monday, August 5th, yields, or interest rates, on

We saw a similar trend in yields on euro-denominated sovereign debt; due to a lag in the reporting of yields on euro-denominated debt, we compare Thursday, July 25th, to Thursday, August 1st:

There have been some tendencies of falling yields on both U.S. and euro zone debt since earlier in July, but the trend became much more pronounced in the past week. With such consistent market pressure, a central bank can only hold out for so long before it gives in and does what the market is demanding, namely cut its policy rates.

One reason for the downward trend in Treasury yields is that money has been trickling out of the stock markets. With rising recession worries, investors do what they always do when it is time to raise the shields against risk: they shift from equity markets with overpriced assets to government debt. As demand for Treasury securities increases, the prices on them go up, and, by logical necessity, the yield goes down.

So far, the decline in yields has been primarily concentrated to the debt instruments that we here in America refer to as ‘notes’, i.e., the mid-range maturities. This is likely to exacerbate an oddity that we have seen in both debt markets, namely inverted yields on government debt in both the euro zone and in America.

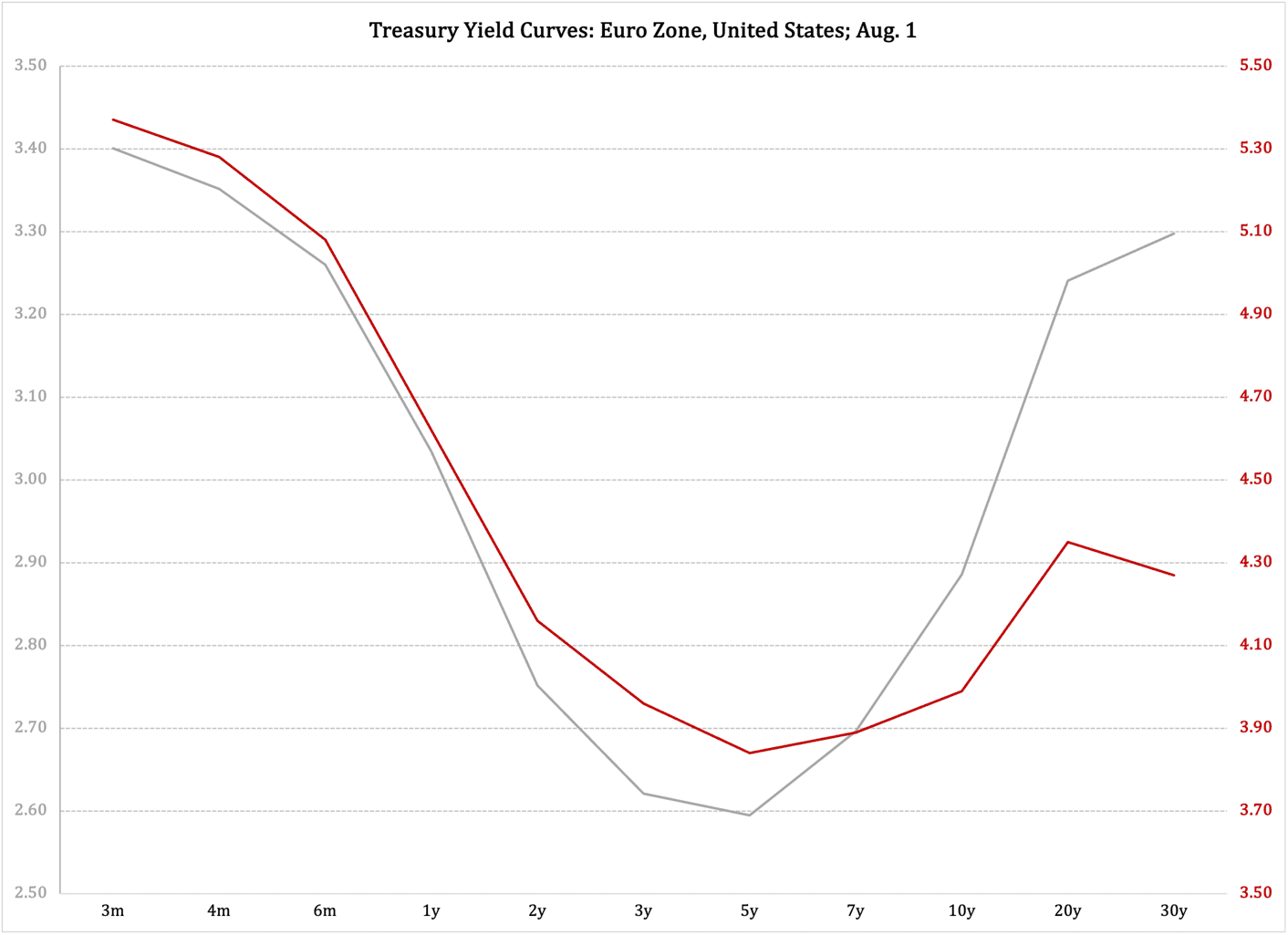

An inverted yield curve is, plain and simple, a curve where shorter maturities pay more than longer maturities. This goes against market logic, since an investor who gives up his money for a longer period of time should be compensated for the higher risk that is associated with a longer commitment. But neither euro- nor U.S. dollar-denominated government debt follows this basic logic—and instead compensates investors as follows:

Figure 1

While the U.S. yield curve (red) ‘ends’ in a small upward kink and modestly higher yields on the 20- and 30-year bonds, the euro-zone yield curve (gray) is an almost perfect V. This is even more absurd than a simple inverted curve: a euro zone investor can spend the same 3.3% yield on a 6-month and a 30-year government security and get the same annual return.

Meanwhile, if he were to drop the same amount of money into a five-year security, his return would only be 2.6%.

As long as it pays more to make short-term investments in government debt than it does to make long-term investment plans, the entire system of financial markets will have a short-sighted bias. If I can roll over, say, €1 billion on one-month Treasury bills and get €36 million in return per year, then I would be a fool if I instead chose to invest my €1 billion in five-year Treasury securities and only get €26 million per year.

Over the course of five years, my short-sightedness makes me an extra €50 million.

Both the American and the European economies would benefit from getting back to ‘normal’ yield curves. Hopefully, the downward pressure on yields from the debt markets will help that transition happen. If it does, the allocation of risk capital in the economy will be more sound, there will be less speculation, and consumer credit—essential for an economic recovery—will gradually become more affordable.