Europe and America need to rein in their government deficits. They need to stop spending borrowed money. There is no option, yet it is hard to find a politician who will do anything about it.

Many of them actually like budget deficits. They would be hard-pressed to admit as much in public, but the reason why they like to spend borrowed money is that it allows them to dole out more money without having to raise taxes.

The aversion to higher taxes is not as strong in Europe as it is in America, but there is no doubt that Europeans are growing weary of paying through the nose for their governments. The question that voters and taxpayers on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean still have not addressed is what should happen to government spending.

People seem to prefer to reap the benefits from a generous government, even as they themselves are not willing to pay more to secure those benefits.

Until voters and taxpayers align their preference for government benefits with their preference against higher taxes, both European and American politicians will continue to run budget deficits. They will do this despite knowing that it is an unsustainable fiscal practice: underlying the preference for deficits is the explicit or implicit notion that the cost of growing public debt will not come due until at some distant future point in time.

Based on my own experience from many years working in American politics, I can certify that even in personal conversational settings, it is near impossible to find politicians who pay more than lip service to the U.S. government’s deficit problem.

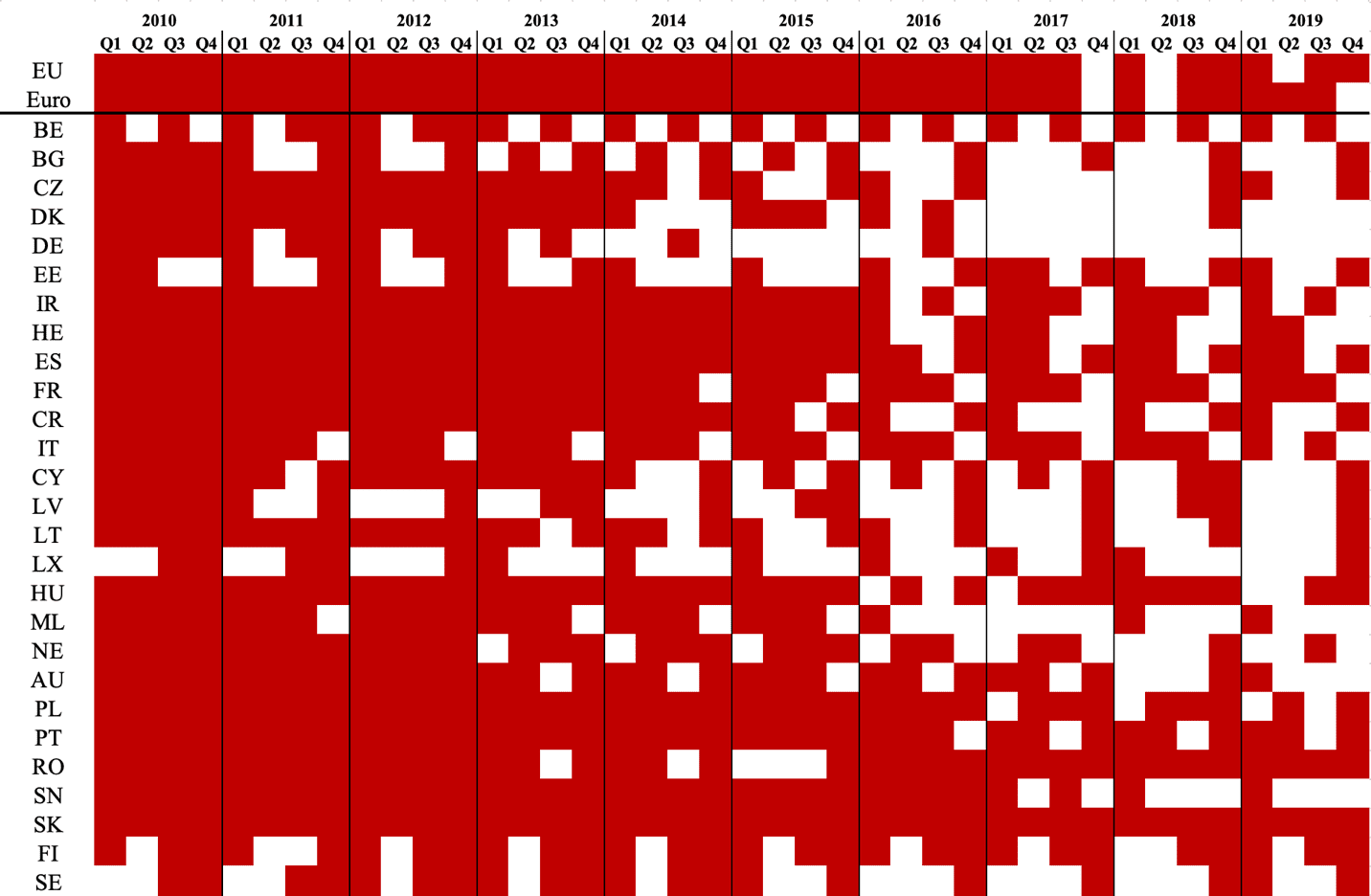

The situation in Europe is not much better. A good way to see this is to look at just how widespread the deficit-spending practice actually is. Figures 1a and 1b report budget deficits in all 27 EU member states, on a quarter-by-quarter basis. Red rectangles mark deficits; white rectangles mark budget surpluses.

Figure 1a starts in 2010, a year dominated by the recovery from the Great Recession of 2008 and 2009. Expectably, almost all EU states ran budget deficits every single quarter of that year. Belgium is an interesting exception, with deficits in the first and third quarters but surpluses in quarters 2 and 4:

Figure 1a

Source of raw data: Eurostat

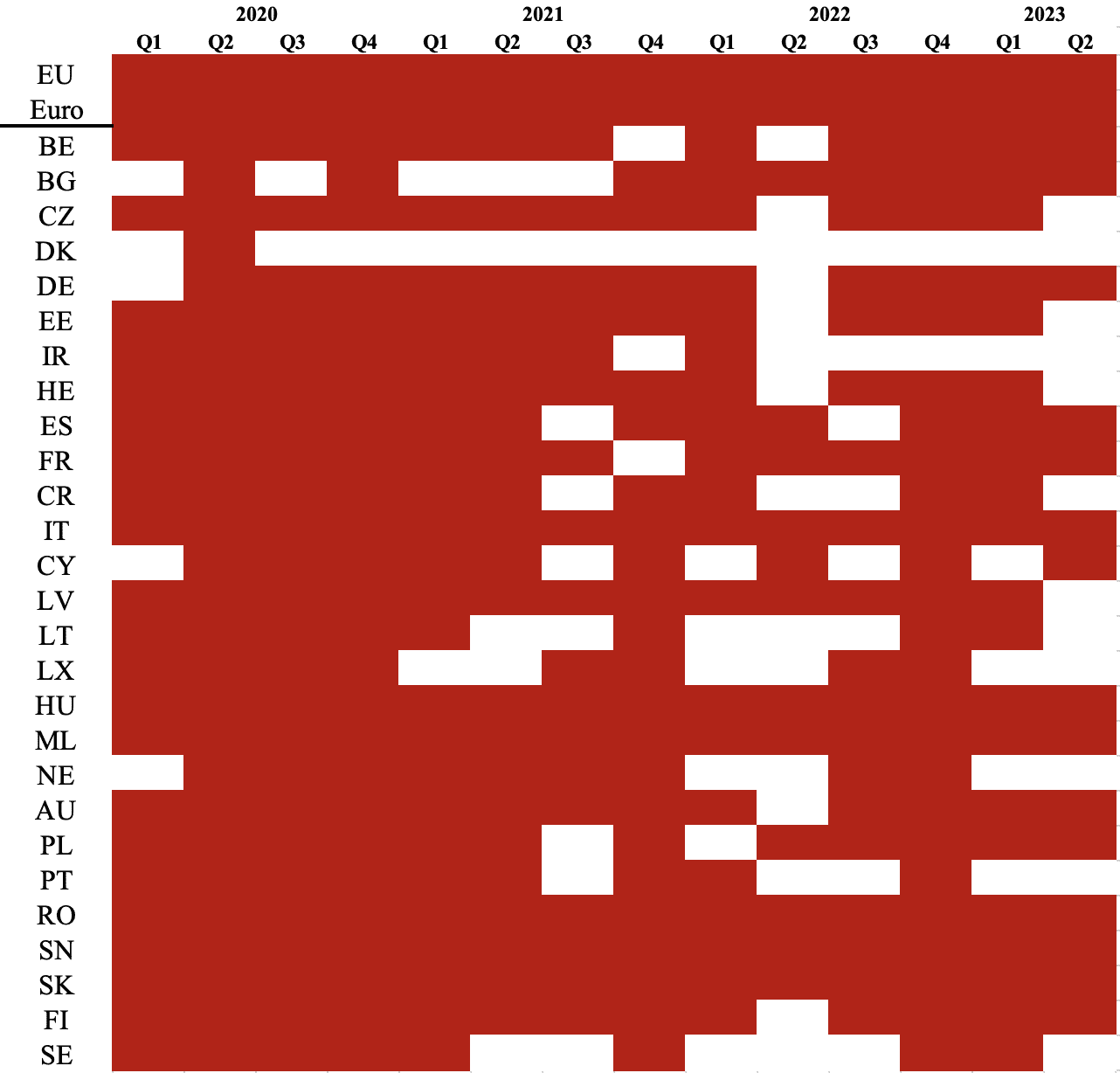

Figure 1b continues from 2020 through the first half of 2023:

Figure 1b

Source of raw data: Eurostat

Colloquially, there is a lot of red in Figures 1a and 1b. The first figure captures an interesting but hardly surprising deficit trend: in 2010 and the next couple of years, deficits are rampant across the EU. As the decade unfolds, the white squares slowly gradually replace the red ones, but the trend of improving government finances never gets strong enough to sustainably balance government budgets across the EU.

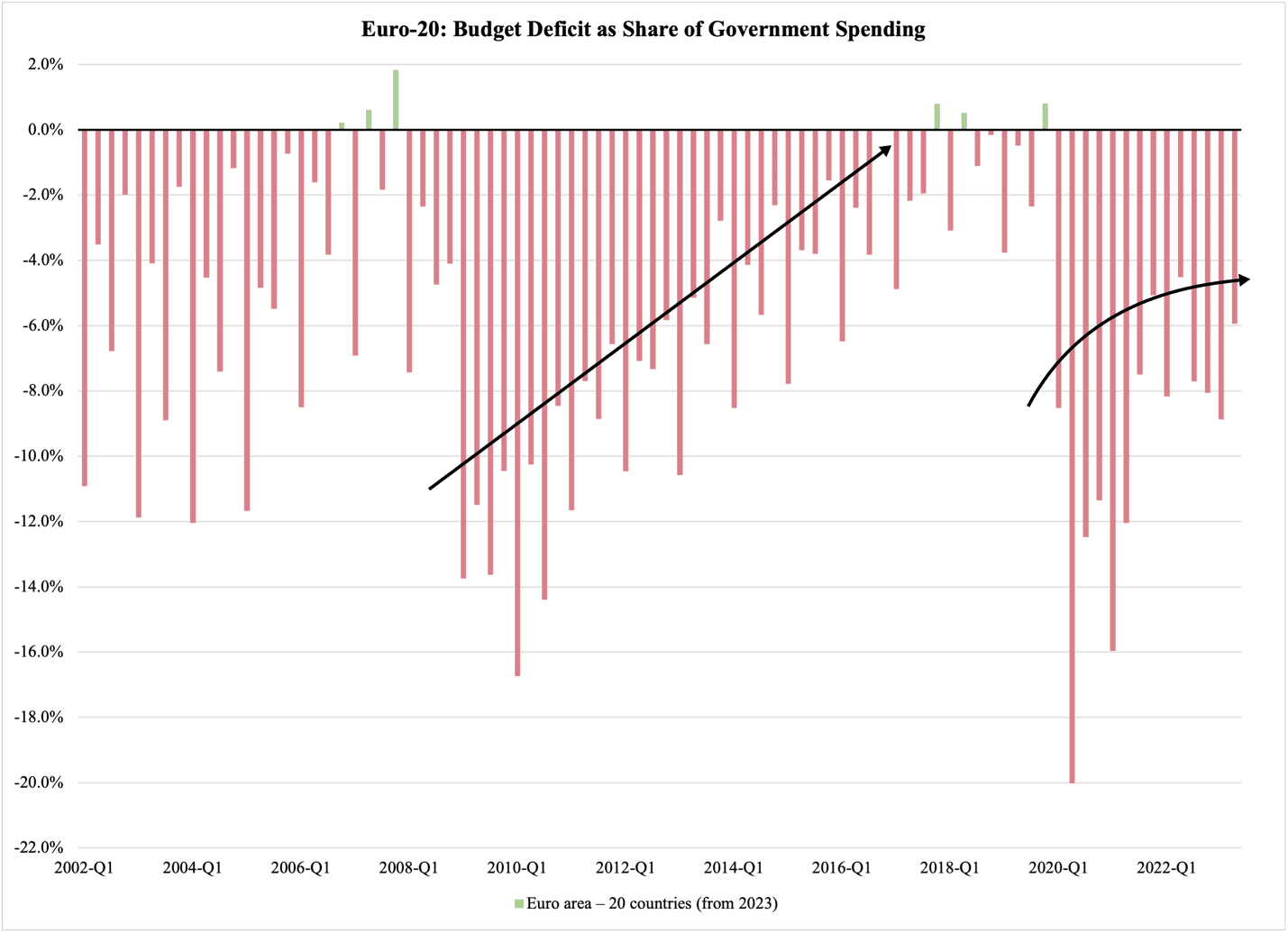

When the pandemic hit in 2020 and governments all over Europe executed forced economic shutdowns, budget deficits once again skyrocketed. Just like a decade earlier, governments around the EU experienced considerable difficulties in returning to budget balance. This time, though, as can be seen in Figure 2, the trend of improvement was even weaker. The columns in Figure 2, which are red for deficits, illustrate the budget balance as percent of total government spending:

Figure 2

Source of raw data: Eurostat

The straight arrow shows how the average budget deficit for the euro zone shrinks as the 2010-19 decade unfolds. The currency area eventually reaches a point of almost-balance in government finances just before the pandemic-related economic shutdown opened new holes in public finances.

The curved arrow illustrates the sluggish recovery from the pandemic; the widespread presence of red in Figure 1b translates into a sustained budget deficit for the euro zone as a whole. Unlike the preceding decade, though, that average deficit is persistent; as Figure 1b suggests, numerous EU member states—inside or outside the euro zone—are unable to produce more than, at best, the occasional quarter with a budget surplus.

This creates a major problem, of course, when government indebtedness reaches that critical boiling point when investors in sovereign debt no longer have full faith in the governments they lend money to. Unfortunately, there is nary a whiff of conversation in the European Union about this problem. The reason for this might have to do with the experience from last time the euro zone faced an acute debt crisis. Back then, the ECB was complicit in forcing destructive austerity policies upon Greece; nobody wants to relive that experience, yet nobody wants to learn from it.

Americans are showing more interest in measures to bring budget deficits under control. Mike Johnson, the new speaker of the House of Representatives, has repeatedly made commitments to fiscal conservatism. Most recently, in an interview with Larry Kudlow on CNBC, he explained:

The Treasury Department this week said we’re going to have to borrow over $1.5 trillion additionally just to keep the government in operation for the next two quarters. This is an unsustainable track.

This expression of interest in curbing the growth of government debt is refreshing, and it might even inspire some Europeans to look more closely at what Speaker Johnson can accomplish.

I would encourage them to look more closely indeed, but I would also advise Europe’s fiscal policy makers to look carefully at exactly how the House of Representatives would address the debt-and-deficit problem. The reason is simple: the only method that has been proposed is one that has already been tried—and failed.

The idea gaining traction in the House is to appoint a bipartisan commission to discuss the problem with the government debt, and to propose solutions. This is not a new idea, nor is it one that has much of a promise to it. Barack Obama appointed a debt commission early in his first term as president, with bold ambitions and pale accomplishments.

The problem with the so-called Simpson-Bowles commission—named after its two most prominent members—is that it focused on closing the budget gap, not eliminating the causes of the gap. To see what this means, let us take a look at three ideas from the commission report.

1. Caps and growth restrictions on discretionary spending.

This category, which accounted for 26% of total federal spending in 2022, is a heterogenous category of outlays that really only have one thing in common: they are not ‘mandatory’ outlays. Counted under this label is spending on government procurement, transfers of funds from the federal government to the states, and wages and salaries for federal employees. Among the items proposed here was a cap on the growth of spending “to half the projected inflation rate through 2020.”

This proposal is a classic example of how fiscal conservatives, in their eagerness to limit government spending, treat the symptom of the deficit instead of its cause. As one example, approximately 10% of non-defense discretionary spending goes to income-security programs. These programs provide benefits to the poor and to certain low-income groups; when spending on these programs grows more slowly than inflation does, the value of the benefits erodes.

By eroding the value of these benefits, the government defaults on promises it has made to take care of its poorest and most vulnerable citizens. Government does nothing in return to improve the opportunities for these individuals to compensate for the benefits erosion. Therefore, its promise default effectively pushes the burden of government promises over to the private sector—without the private sector being given better tools to provide for those in need.

To avoid this type of responsibility shifting, a cash limit on welfare spending must be part of a package of positive and negative reforms. While the negative reform would be a real reduction of the value of the benefits, the positive reform would be one that: a) facilitated for charities to fill the holes left empty by government, or b) improved help to those in need of a job, or more jobs training, to get this.

The 1990s welfare reform that President Clinton, a Democrat, passed in cooperation with a Republican-led Congress, was a good example of how positive and negative reforms can be balanced against each other. Since then, Congress has gradually eroded the standards of that reform, but it is nevertheless a good role model for reforms to welfare-state benefits programs.

It is worth noting that the Clinton-era welfare reform was designed to reduce government spending, not to close the budget deficit—because there was no budget deficit during President Clinton’s second term in office.

2. Establish a long-term total health-care budget with a firm cap on spending growth.

Turning to so-called mandatory spending, the Simpson-Bowles commission proposes a cap on government health care spending at the growth rate in current price GDP plus one percentage point. If GDP, including inflation, grows at 2.5%, health care spending can grow by 3.5% that year.

Technically, the commission proposes a five-year moving average for GDP growth, but the fiscal impact is the same as if we use one year at a time. Like the proposal for capping discretionary spending, this limit on health care outlays applies ‘cash limits’ to a spending program without proposing any reforms to the promises made in that program.

Users of health care in many European countries are well aware of what this means. Those who depend on the British National Health Service or any kind of health care in Sweden know that such cash limits translate into long waiting lists, rationed health care, inaccessibility, and—where legal—increased prioritization of euthanasia.

The idea is, again, to maintain the government programs and thereby keep promising everything that these programs already pledge to provide people with. Then, to deliver on all those promises, the federal government would cap the growth rate of its budget—regardless of the growth rate of health care spending.

A quick review of U.S. health care spending, both government and private, in comparison with GDP growth, suggests harsh repercussions from the Simpson-Bowles cash limits idea. Assuming that today’s health care programs had existed in 1964, and the cash limit had been applied that year, then already after ten years government outlays for health care would have been 23% below its actual historic numbers.

Who should have been denied health care under those circumstances? Again, a reform to reduce spending, i.e., to improve private provision and funding of health care, would tackle the cause of the budget deficit, instead of the symptom.

2. Maintain or increase progressivity in the tax code.

The Simpson-Bowles report suggests that although

reducing the deficit will require shared sacrifice, those of us who are best off will need to contribute the most. Tax reform must continue to protect those who are the most vulnerable, and eliminate tax loopholes favoring those who need help the least.

This is a classic example of a proposal that goes into a bipartisan agreement purely to satisfy ideological preferences among the people on the left. Any increase in the progressivity of an income tax system will discourage people from pursuing higher incomes and more skilled jobs. Workers will be less inclined to invest in education and career development, and fewer will want to take the risks associated with starting a new business.

When this idea is coupled with a proposal to tax income from capital gains and stock dividends at the same rate as work-based income, the commission clearly takes a left-of-center stance on taxes. There are numerous reasons why higher taxes on equity-based income is a bad idea—we can return to them in a separate article—but the overarching problem is precisely this: the output is a mix of ideological ideas, not workable economic solutions.

Taking these three proposals together, we get the picture of a debt commission that was focused on band-aiding the symptom, not treating the underlying illness. Let us hope that both European and American politicians do better in the future.