The European Central Bank’s cut to its policy rates last week will help the euro zone economy navigate the next year a bit more easily. If this rate cut and the one in June will be the only cuts the ECB makes to stimulate the European economy, there is a good chance that we will see a euro zone on the rebound a year from now.

If, on the other hand, the ECB cuts rates more than they already have, there is a fair chance that inflation may return long before the euro zone economy is back to growth and full employment.

I am not the only one urging the ECB to be cautious. According to Reuters, ECB Governing Council Member Peter Kazimir

should almost certainly wait until December before cutting interest rates again to be certain it is not making a policy mistake

The mistake, of course, would be to reignite inflation on a euro-zone-wide level.

With these broad strokes in mind, it is nevertheless important to keep in mind that neither Europe as a whole nor the euro zone itself are coherent economic areas. They are composed of 20 (euro zone) or 27 (EU) member states, among which the economic landscape varies quite a bit. Therefore, to get a better understanding of where Europe is today economically, we need to delve into nation-specific numbers and the information they reveal.

Since Eurostat has just recently completed its full national accounts database for the second quarter of this year, let us see what those numbers tell us.

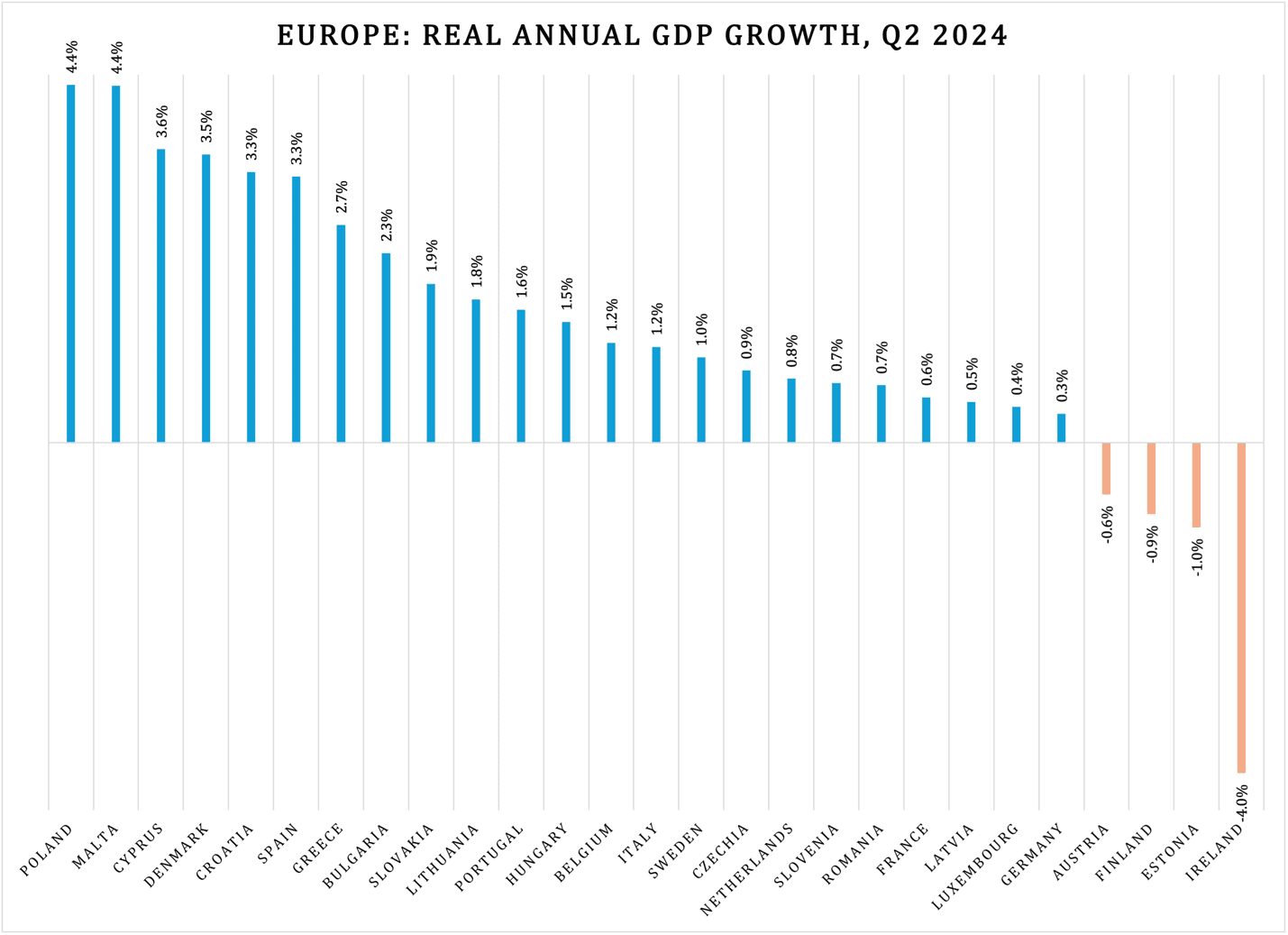

Starting with Figure 1, we get the annual growth rates in inflation-adjusted GDP from all the EU members. The differences are stark, with two countries above 4% and another four countries in the 3-4% range—while, at the same time, four countries have a shrinking economy and another eight saw less than 1% growth in the second quarter:

Figure 1

The wide variety of growth rates is in itself nothing strange; what is telling, though, is that the total European Union economy grew by only 1.0% in real terms, and that the growth rate was even lower, 0.8%, for the euro zone. There is a purely statistical explanation for this: the EU and euro zone average growth rates are weighed down by the lousy performance of the French and German economies. These are the two largest economies in the EU and therefore carry a lot of weight in the statistical average that estimates the EU and euro zone GDP numbers.

At the same time, the poor performance of the French and German economies has meaningful economic implications for the whole of Europe. In both countries, domestic spending seems to have been frozen in time:

Consumer spending is nothing fancy. It is, plain and simple, the outlays that private households have. The large majority of household outlays go toward housing, food, clothing, and transportation, but it includes everything else, from haircuts and privately paid health care to fine dining and buying a Piaget watch.

When consumer spending grows as slowly as it does in France and Germany, it is a sign that household budgets are tight and they try to concentrate their outlays as much as they can on necessities. In short, a virtual standstill in household outlays is a sign that people in general are pessimistic about the near future.

Not all consumers in Europe are pessimistic. In Romania, they increased their spending in the second quarter by an annual, inflation-adjusted 9.5%. That was the highest rate in Europe, followed by five others above 4%: Croatia (6.1%), Cyprus (5.1%), Poland (4.5%), Hungary (4.2%), and Malta (4.1%).

Strong real growth in household spending is the best thing that can happen to an economy. About two-thirds of that spending goes toward services and often pays for jobs in the local economy and by a very large margin supports the national economy. Consumer spending manifests regularity in human activity. If we wanted to take it one step further, we could explain consumer spending as the economic backbone of our society. It necessitates regular, peaceful, and mutually gainful interaction between citizens who are otherwise total strangers; it puts money into millions of pockets, helping parents feed their kids and build a future for their families.

There is always a share of consumer spending that benefits other countries. When a European buys a new computer, there is almost zero chance it was built in his country; a sizable part of the energy that Europe’s households consume has a foreign origin, and so on. However, on average, consumer spending is split 2:1 between services and goods. The items we traditionally associate with imports account for—by rough estimate across Europe’s economies—10-15% of total consumer spending.

In other words, it is good for the current and future economic strength of a country that its households are on solid financial footing and optimistic enough to spend a lot of money. This means that the governments of Romania, Croatia, Cyprus, Poland, Hungary, and Malta should be proud of having designed fiscal policies that have helped make their households more prosperous.

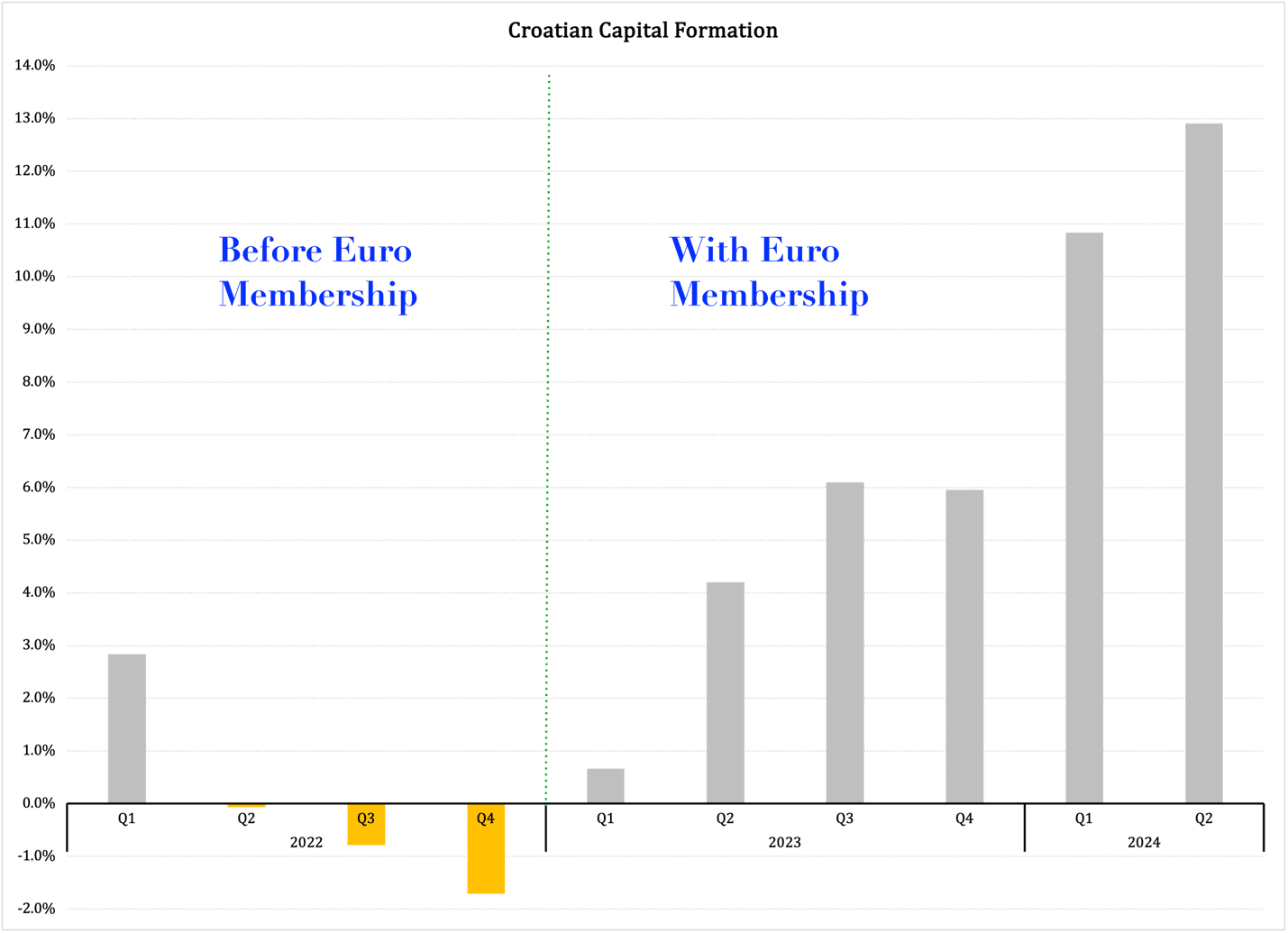

The second most important economic activity is capital formation, a.k.a., business investments. In this category, five countries benefited from 4% or more in real capital-formation growth: Croatia (12.9%), Cyprus (11.1%), Estonia (7.9%), Italy (5.1%), and Greece (4.1%).

Since joining the euro in January 2023, Croatia has experienced an investment boom:

Figure 2

This boom is due entirely to the fact that the Croatian economy, upon entering the euro zone, had a cost advantage relative to established euro members. The so-called terms of trade were simply so beneficial that an investment boom was inevitable.

Croatia should enjoy this boom because it will not last. While foreign direct investment has flooded the country and turned resources from idle to able, this has not yet made any difference in consumer spending. To be fair, over the past couple of years, Croatian households have grown their annual spending at some of the highest rates in Europe, but there has been no identifiable improvement after the euro entry.

This means, bluntly, that foreign direct investors are using Croatia as a facility for the assembly of products for the European market. The investment trend is too young—18 months—to have yet positively affected the Croatian trade balance, but it will. Components will be brought in, screwed together, and shipped off to other parts of the EU. There will be very little value left to add to the Croatian economy.

By comparison, Hungary and Poland have made a wiser choice than Croatia. They have kept their national currencies and therefore been forced to build a different, more long-term oriented strategy for attracting foreign investors. This is paying off now, when, e.g., Hungary is experiencing a decline in capital formation but Hungarian households—as mentioned earlier—can increase their spending by more than 4% per year in real terms. This shows that the foreign investment that has reached Hungary in the past 10-15 years has been of a more substantive economic nature than that which is now pouring into Croatia.