The war in Ukraine is now creeping deep into the fiscal affairs of Europe’s governments. Lithuania is the latest example, as reported by The Baltic Times:

The Lithuanian Finance Ministry on Tuesday [May 21st] proposed increasing the corporate tax rate by one percentage point, hiking excise duty on fuel, and introducing a tax on some insurance contracts as part of measures to raise additional funds for defense.

I am not going to comment on the defense policy priorities in Lithuania. Sharing borders with the Russian enclave of Kaliningrad and the Russian ally Belarus, the government in Vilnius may very well see it as existentially important to beef up its military.

My concern here is strictly with their proposed method for funding their expansion. The proposed tax hikes come at a very delicate point in time for the Lithuanian economy.

There are different reports on the exact nature of the proposed increase in the corporate income tax. According to Baltic Times, it would raise the general corporate income-tax rate from 15% to 16%. At the same time, Lithuanian news site LRT gives the impression that the hike only applies to small businesses and would raise their rate from 5% to 6%.

These two tax hikes are not mutually exclusive—on the contrary, they make sense within a two-tiered corporate tax system. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that the proposal is to raise the corporate income tax across the entire income spectrum.

There is also a proposal for an extension of a so-called windfall tax on banks. Here is how Reuters described the tax a year ago:

a temporary windfall tax on bank profits, aiming to raise an estimated 510 million euros ($538.7 million) over a two-year period. Banking profits have risen sharply on the back of higher interest rates to combat soaring inflation

This definition of the tax means that it is supposed to end when interest rates come down and the banks no longer make “windfall” profits. As the LRT reports, this no longer seems likely:

To ensure extra defence funds for 2025, the [finance] ministry suggests extending the so-called solidarity levy, a tax on windfall profits in banking, for a year.

In effect, the tax now takes on a new form. It is no longer a “solidarity levy” aimed at redistributing exceptional banking profits through the Lithuanian welfare state. It now becomes a means to fund the country’s expansion of its military capabilities.

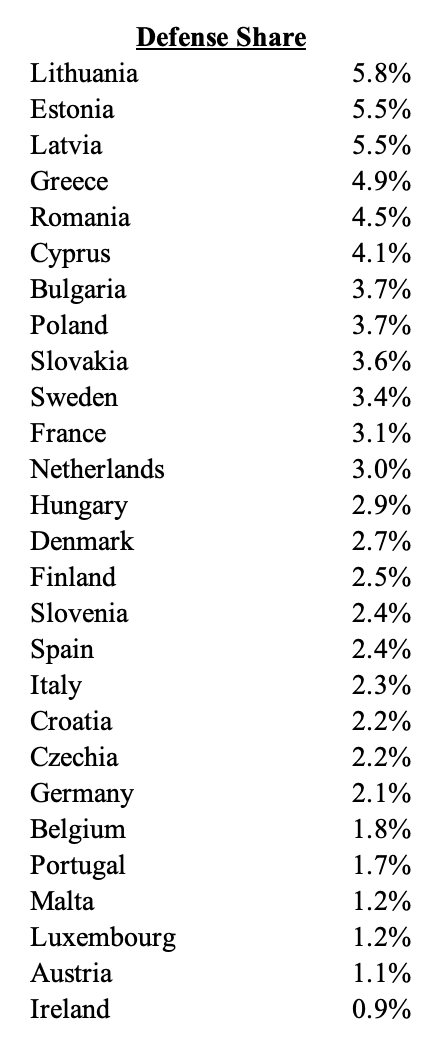

As mentioned, there may be good reasons for Lithuania to further beef up its military. At the same time, it is worth noting that Lithuania already leads the European Union in terms of defense spending as a share of total government outlays. While NATO measures member-state defense spending as a share of GDP, the ratio of defense spending to total government spending is a better tool for explaining policy priorities at the national level.

As Table 1 shows, the three Baltic states top the list of European countries in terms of prioritizing defense in their government budgets:

Table 1

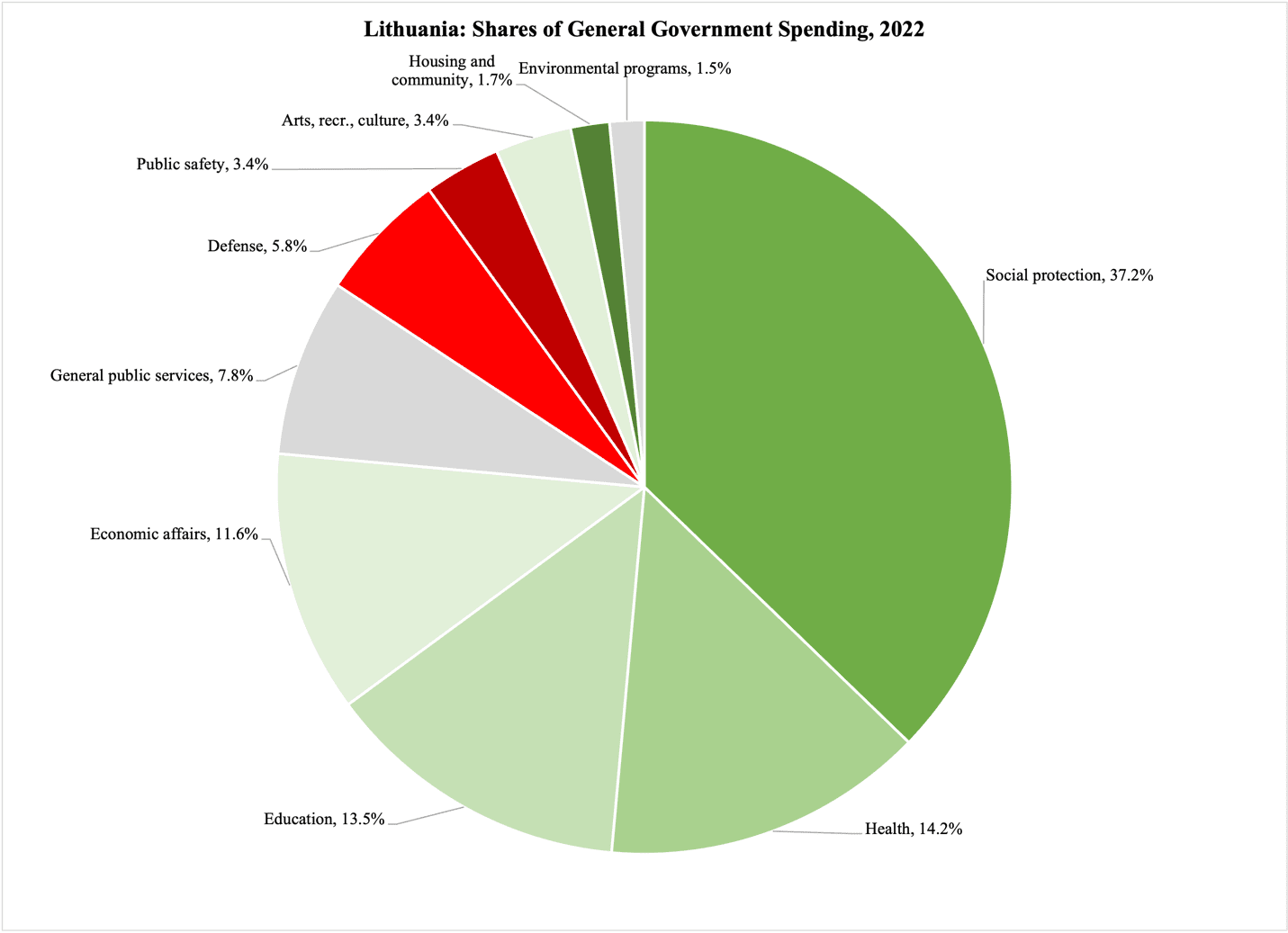

With such a high emphasis on national defense already, the Lithuanian government is going down the tax-hiking route in order to avoid direct policy conflicts with other programs in the budget. Figure 1 explains how consolidated (general) government outlays are distributed in Lithuania:

Figure 1

The ambition to avoid policy conflicts is respectable, but the alternative with higher taxes is not unproblematic either. Higher taxes always take a toll on economic activity, even if the compound effects of those tax hikes do not materialize until a year or two later. However, it is worth keeping in mind that the negative effects of tax hikes tend to set in more quickly than the positive effects of tax cuts. Therefore, the timing of a tax hike is more sensitive than the timing of a tax cut.

In Lithuania’s case, the proposed tax increases are not well-timed. Unemployment has been on the rise recently, from 6.2% in September last year to 9% in January; it fell modestly in February and March to 8.2%, but it is still much higher than the 6-6.5% levels common before the 2020 pandemic.

Youth unemployment is even more problematic, averaging 20.7% so far this year. There is a slight downward trend in the numbers, but it is too weak to be of any consequence to the economy—at least for now.

On the inflation front, Lithuania has made great strides. After a top of 22.5% in September 2023, it now boasts Europe’s lowest inflation rate at 0.4%. This has a stabilizing effect on price-sensitive markets, but it also shows the risks of inflation-inducing taxes. Since Lithuania currently enjoys virtual price stability, it is an attractive economy for investors and entrepreneurs. With the prospect of tax hikes reigniting inflation, this positive outlook could evaporate radically.

To be clear, the risk is not significant that inflation would return as a result of these tax hikes, though any uptick in inflation would be unfortunate. A bigger problem for Lithuania is that the higher taxes are to kick in right when the economy is at the bottom of a business cycle: since the fourth quarter of 2022, the Lithuanian economy has been standing still. The average year-to-year growth rate has actually been negative at -0.3%.

Combined with the elevated unemployment rates, a stagnant economy spells trouble, both for the Lithuanians in general and for their government. When the broadest possible base for their tax revenue, GDP, is not growing at all, government reasonably should not be growing its spending. To add more taxes to a stagnant economy is, frankly, to play with macroeconomic fire.