On May 1st, 2004, the European Union underwent its largest expansion to date. The union grew from 15 countries to 25 when Cyprus, Czechia, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia became members.

Since then, three more countries have joined, while Britain has left the union. The most recent new member, Croatia, entered the EU in 2013.

The expansion in 2004 was one of the most significant moments in the history of European integration. It involved seven countries that during the Cold War were part of the Soviet bloc, and Slovenia, which had gained independence from communist Yugoslavia. It was significant also because of its size: it was a daunting effort to expand the number of EU member states by two-thirds—and to do it practically overnight.

When these ‘2004 states’ began moving toward membership, it was commonly argued that EU accession would benefit their economies. By being integrated into a common market, the understanding was that the 2004 states would see GDP grow, their standard of living improve, and foreign direct investment increase.

Looking back on the past 20 years, was it worth the while to join the European Union?

From an economic viewpoint, the answer is the classic economist’s aphorism: ‘It depends.’ The best way to describe the experience of the 2004 states is that the EU membership was no autopilot to growth and prosperity—if anything, it gave them an opportunity to do well. Whether they did or not was then up to the government of each individual country.

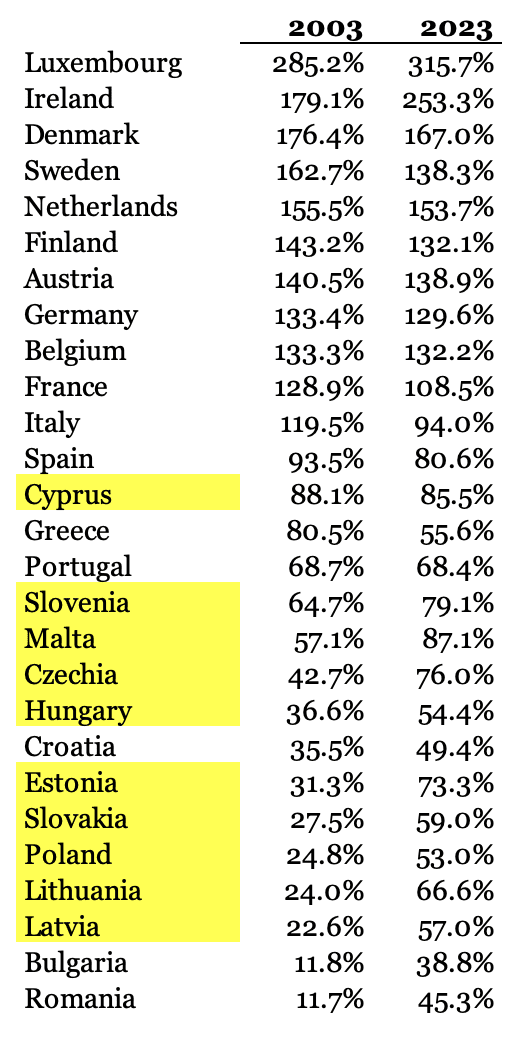

In economic comparisons between countries, it is common to use gross domestic product, GDP, per capita as a measurement of how prosperous a country is. Table 1 reports this metric, but not in absolute terms. Each individual member state is compared to the average for the current 27 EU member states. Cyprus, e.g., had a GDP per capita in 2003 that was 88.1% of the EU-27 average; in 2023, it had fallen to 85.5% of the same average.

Table 1

All GDP per capita numbers are calculated in euros. While this makes the statistical comparison transparent and simple, it also adds a skewed element to the numbers. Of the ten countries that entered the EU in 2004, only seven have thus far joined the euro zone. The remaining 2004 states—Czechia, Hungary, and Poland—together with the other EU states that maintain their own currencies, are at least hypothetically at a disadvantage. While the Polish zloty has remained essentially pegged to the euro since the common currency’s introduction in 1999, the Czech koruna strengthened toward the euro until 2009, when its exchange rate vs. the euro stabilized.

For both these countries, the GDP-per-capita comparison to other EU states is not dramatically affected by the exchange rate between their local currencies and the euro. The situation is different for Hungary, which has experienced a slow but consistent currency depreciation since 2010. This puts Hungary at an artificial disadvantage in a same-currency comparison: when we ‘translate’ national Hungarian GDP numbers to euros and the forint gets weaker over time, the ‘translation’ makes it look like the country’s economy is weaker than it actually is.

In reality, the Hungarian economy is a powerhouse. As one of Europe’s absolutely best, it attracts major volumes of foreign direct investment and produces highly respectable numbers in practically every macroeconomic category.

In other words, the comparison in Table 1 is not entirely fair. We could make the same comparison in national currencies, but we would just have the same problem as in Table 1, only flipped on its head. A better way to assess whether or not the 2004 states have benefited from their EU membership, is to look at traditional macroeconomic performance numbers. Foremost among them is real GDP growth.

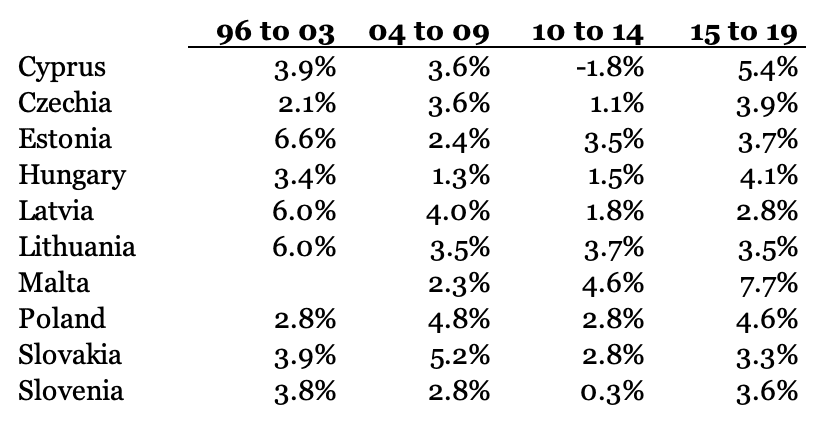

Table 2 reports the average annual growth rates in GDP (in national currencies) for the 2004 states. The numbers are divided into four periods:

The numbers are quite interesting:

Table 2

Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania had their strongest economic growth period prior to joining the EU. This observation tends to invite comments about how the former Soviet satellites had a lot of catching up to do; investments in modernized infrastructure, productive capital, and a top-trained workforce necessarily led to a growth spurt.

This is a good observation, but it does not explain the other numbers in Table 2. Czechia and Poland have had two stronger periods since joining the EU, while the Hungarian economy accelerated notably after the Great Recession, when a Fidesz government under Viktor Orbán could start putting its long-term economic growth strategy to work.

Overall—with acknowledged exceptions—it looks as though the 2004 states actually suffered to some degree from their EU memberships. There is a grain of truth in this, and it is tied to the fiscal policy that a prospective EU member has to commit to. In order to keep their budget deficits below 3% of GDP and their government debt at no more than 60% of GDP, many member states—not just these ten—have had to raise taxes and cut government spending. Inevitably, such policy measures depress GDP growth.

The focus on fiscal compliance with the EU’s stability and growth pact (or whatever it will be called going forward) has not been universal. The Fidesz government had somewhat different economic priorities during the 2010s than its predecessor governments had in the preceding decade. While tolerating moderate budget deficits, they focused on policies that helped the domestic private sector grow, and—as mentioned—invited large foreign direct investments. These two policy measures have been part of a broad, deliberate policy strategy: the Hungarian economy averaged 4.1% real GDP growth in 2015-2019.

In many ways, Poland followed the Hungarian example in the last decade, while others in this group of EU member states did not fare so well.

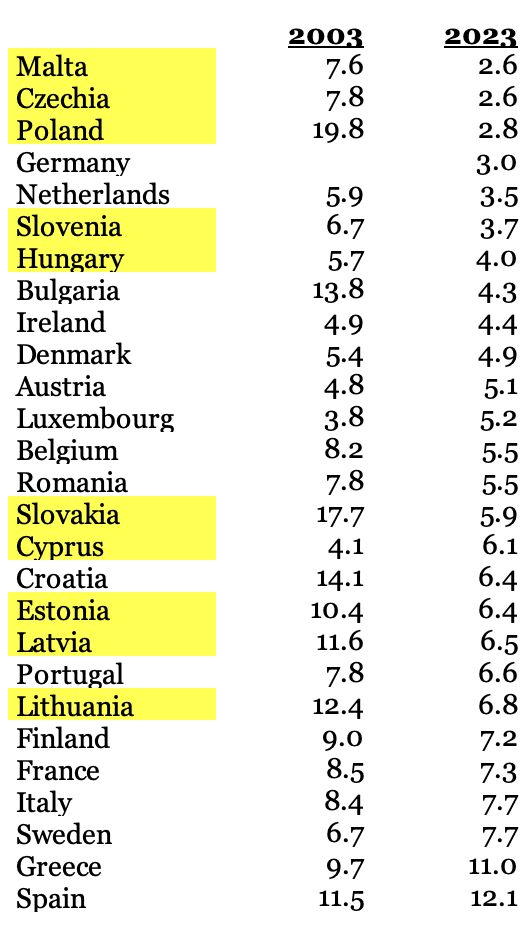

We can see a similar pattern in unemployment numbers: EU membership is a success story if the country’s government wants it to be. Table 3 reports the average total unemployment rates in all current EU member states inDecember 2003 and the same month in 2023. With the member states sorted by 2023 figures, we see the 2004 accession countries splitting into two groups:

Table 3

The high-performing 2004 states have not only brought their long-term unemployment rates down significantly but also managed to keep them below 5%. The weaker 2004 economies are struggling with unemployment rates in the 6-7% range.

In fairness, most EU member states have brought down their jobless rates over the past 20 years. However, given the relatively weak economic conditions of the 2004 states upon EU accession, it is commendable—to say the least—that some of them have risen to economic leadership in Europe.