It caused quite a stir in the media last week when the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, BLS, adjusted its jobs report for 2023 through November. As Fox Business reports, the BLS “quietly erased 439,000 jobs” which means that “the job market is not as healthy as the government suggests.”

This adjustment is a big deal, but not as big as some in the media appear to want to make it. Statistical agencies regularly revise so-called preliminary numbers, which is completely natural. When, e.g., the BLS produces its preliminary jobs report for a month, it has a very limited set of new data available. In order to be able to produce the report, they plug in whatever new numbers they have into an estimation model.

The purpose of the model is to, so to speak, fill in the blanks. A comprehensive analysis of jobs data for any given month requires the processing of an enormous amount of data. By the time the preliminary jobs report is published, most of the data for the comprehensive report is still on its way into the analytical process. Therefore, in order to deliver early, preliminary reports, the BLS replaces the facts they have not obtained yet, with estimated numbers that they derive from their estimation model.

We can also refer to these numbers as ‘hypothesized data.’ There is nothing strange about using such data, but for every hypothesized number that replaces empirical data in an economic analysis, the outcome of that analysis moves another step away from reality. As empirical data trickle in, the statistical agency makes revisions—and when those revisions become big enough, they publish them.

Just like the BLS did.

If that was all there was to the latest jobs report, there would really not be much of a story. However, there was another aspect to the adjustment this time. Fox Business again:

Since the government wiped out 439,000 jobs after the fact, the total percentage of jobs created by the government last year is even higher. Increased government hiring has been driving the jobs numbers higher.

This is an important point, and there is plenty of backup for it in the BLS sectoral data on employment. As Figure 1 shows, a sharp shift in jobs creation took place last year. Before the 2020 pandemic disruption, the private sector (green) was creating jobs at three times the annual rate compared to government (red). However, when the economy returned to normal again, government suddenly accelerated its jobs creation, and did so to the point where tax-paid jobs grew faster than tax-paying jobs:

Figure 1

In 2014-2019, the number of jobs in the private sector grew by 1.9% per year, while government jobs increased by 0.6% per year. These were, so to speak, the normal numbers. However, in 2023, almost two years out from the disruptive effects of the pandemic, jobs creation was anything but normal. In January and February, the private sector expanded its payrolls by 3.6% and 3.1%, respectively, then their jobs creation slowed down markedly. In November and December, private-sector employment grew by less than 1.7% on an annual basis.

By contrast, federal, state, and local governments accelerated their jobs creation significantly, from 1.75% in January to 3.1% in December. In June, government overtook the private sector, expanding employment by 2.7%, compared to 2.4% on the private side. Since then, government has added jobs at a higher pace every month than the tax-paying sector has.

On average, governments in the United States expanded their payrolls by 2.5% in 2023, compared to 2022. This rate is almost five times higher than the 2014-2019 average.

Where have those jobs shown up? Judging from the news stories that have touched upon the subject, one can easily get the impression that the federal government has been on a hiring spree. According to the BLS numbers, the federal government did indeed hire quite a few people in 2023, with its payroll expanding by more than 2% over the previous year for seven consecutive months (June through December). However, in actual numbers, the federal government has only added 61,000 jobs in 2023, for a total of 2,930,000 employees.

The states were far more prolific, hiring 155,000 new employees last year. Not only did this represent a 3% annual increase, the highest at the state level since 1977, but the expansion accelerated. In January, the states increased their jobs by 1.2% year over year; in March the rate was 2.4%; in June it reached 3%, only to finish the year in December at 5.2%.

This practice of hiring more people faster was not copied by local governments, but they nevertheless expanded payroll steadily at 2.4% in 2023.

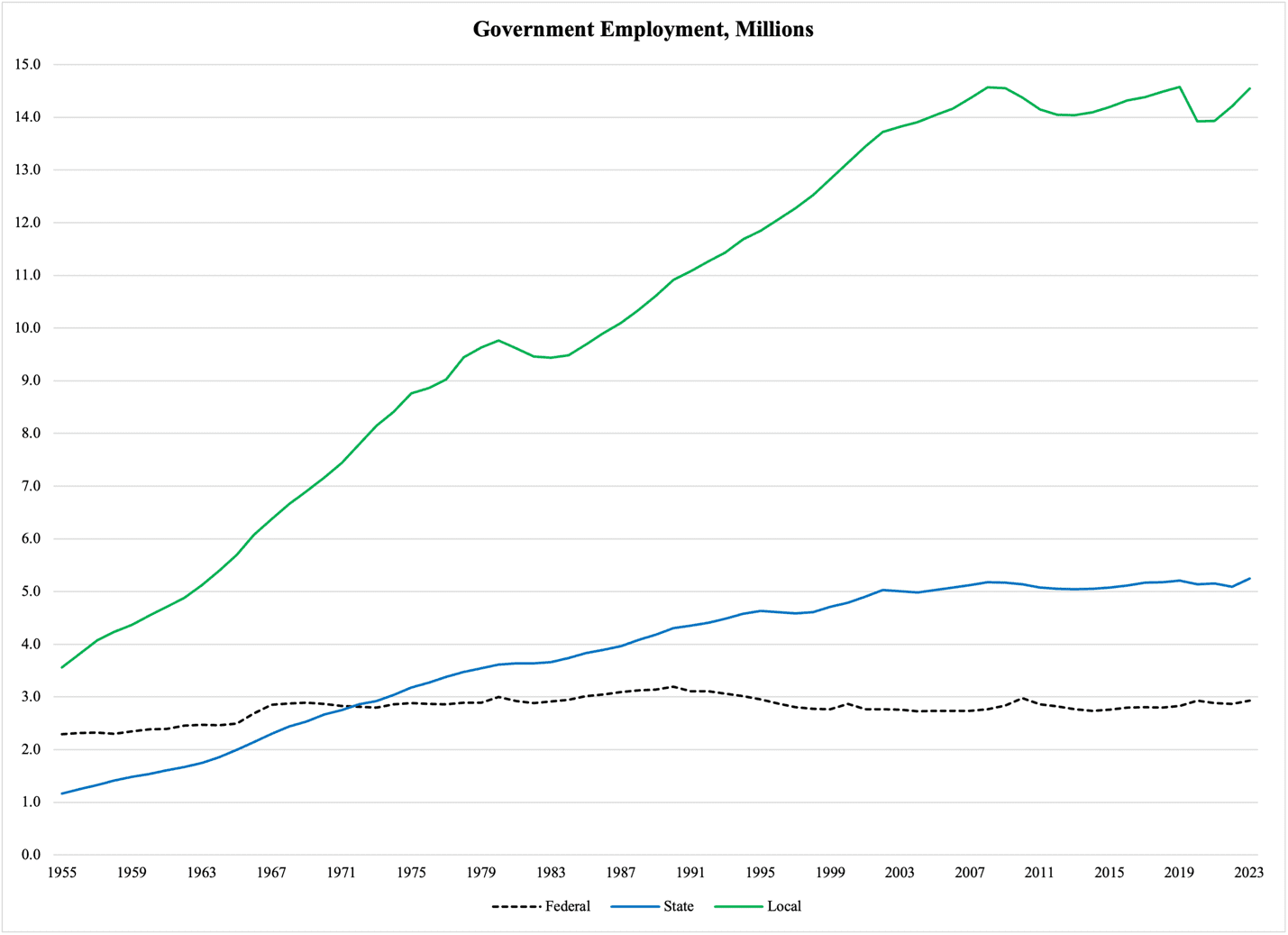

Historically, local governments have been driving the growth in government payroll. As reported in Figure 2, over the 50 years from 1955 to 2005, counties, cities, towns, school districts, and other local government jurisdictions (green function) quadrupled their number of employees, from 3.5 million to 14 million. Over the same period of time, states (blue) quintupled their payrolls, but at smaller numbers: from 1.1 million in 1955 to 5 million in 2005.

The federal government (dashed line) expanded its payroll by 19%, a small number by comparison:

Figure 2

The 2023 hiring spree by governments all over America is indeed conspicuous, and if it continues into 2024, it could start putting some noticeable stress on some state and local government budgets. So far, though, it has not changed the balance between the private sector and government. In 2023, 14.6% of all employed Americans worked for one government or another; with the exception of 2022 when that number was 14.5%, this is the lowest government share of total employment since 1957.

Put differently: in 2022 and 2023 there were 170 government workers per 1,000 private-sector workers, the lowest ratio since 1956 (accounting for rounding errors). In the 1970s, this government-to-private payroll ratio exceeded 224, which means that in terms of the number of employees, the private sector has outgrown government over the past 50 years.

That does not mean government overall has gotten cheaper, but it helps us put the latest, somewhat sensationalized jobs numbers in perspective.