Two years ago, in an analysis of the post-Brexit British economy, I concluded:

So far, Brexit has been a British success story. If it continues to be, it is likely to inspire other countries to consider their own secession from the European Union.

The success was economic: the British economy just kept going after Brexit. The doomsday stories about what would happen after Britain regained her independence, fell flat to the ground. With a successful exit from the European Union, Britain could look forward to a bright economic future, free of regulations and other constraints and burdens imposed by EU membership.

Sadly, the Brits have squandered the great opportunity that Brexit offered. Two years after my analysis and four years after Brexit, the British economy is nowhere near the powerhouse it could have been. The recent GDP numbers show an economy in stagnation, with unemployment creeping upward and inflation persistent at way too high levels.

It is important to note that while Brexit has brought no gains, it has also not inflicted any significant losses on Britain. However, the general absence of negative news is not exactly impressive, given what a major change Brexit brought and what opportunities it opened.

The most important economic variable in assessing Britain after Brexit is gross domestic product, GDP. The OECD has published GDP numbers for 3.5 years, or 14 quarters, since Brexit went into effect; we count the first quarter of 2020 as a ‘pre-Brexit’ quarter. From the second quarter of 2020 through the third quarter of 2023, the British economy grew by an inflation-adjusted 1.25% per year on average. During the pandemic and its recovery in 2020 and 2021, GDP grew by an average of 1% per year.

In the last 14 quarters when the British economy was part of the EU, the average annual growth rate was 1.65%.

This does not mean that Brexit caused a decline in growth. Britain is not the only country that has seen slower economic growth after the pandemic. However, these numbers show that the Brits have not used Brexit to solve a self-inflicted, structural economic problem that keeps their economy virtually stagnant.

In the four most recent quarters, British GDP has grown by

With an average of 0.4% per year for this period, the British economy trails 15 EU member states for economic growth. Among them are Spain (3%), Greece (2.6%), Ireland (1.2%), Italy (0.9%), and France (0.6%).

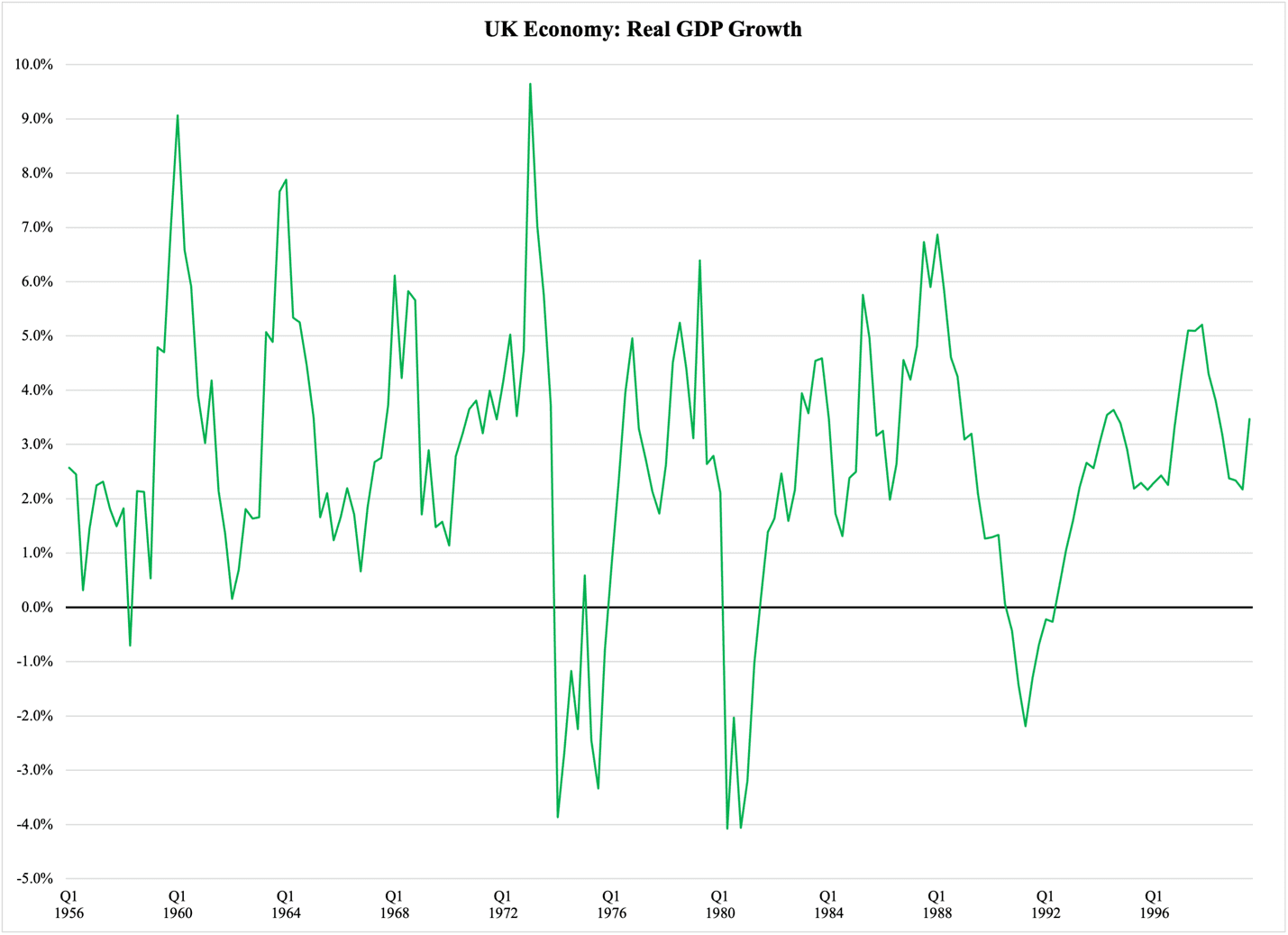

As mentioned, the reason for this slow growth is self-inflicted, but before we look at it in more detail, first let us review the recent history of GDP growth in Britain. Figure 1a reports real annual growth rates (observations are quarterly, hence the sharp swings) from 1956 through 1999. In the 44 years covered, it was common to see GDP grow at 3% or more; correspondingly, growth rates below 2% were unusual and confined to recessions.

Figure 1a

In other words, during this period, the Brits enjoyed at least the same expansion of economic opportunities and their standard of living as people in other European countries.

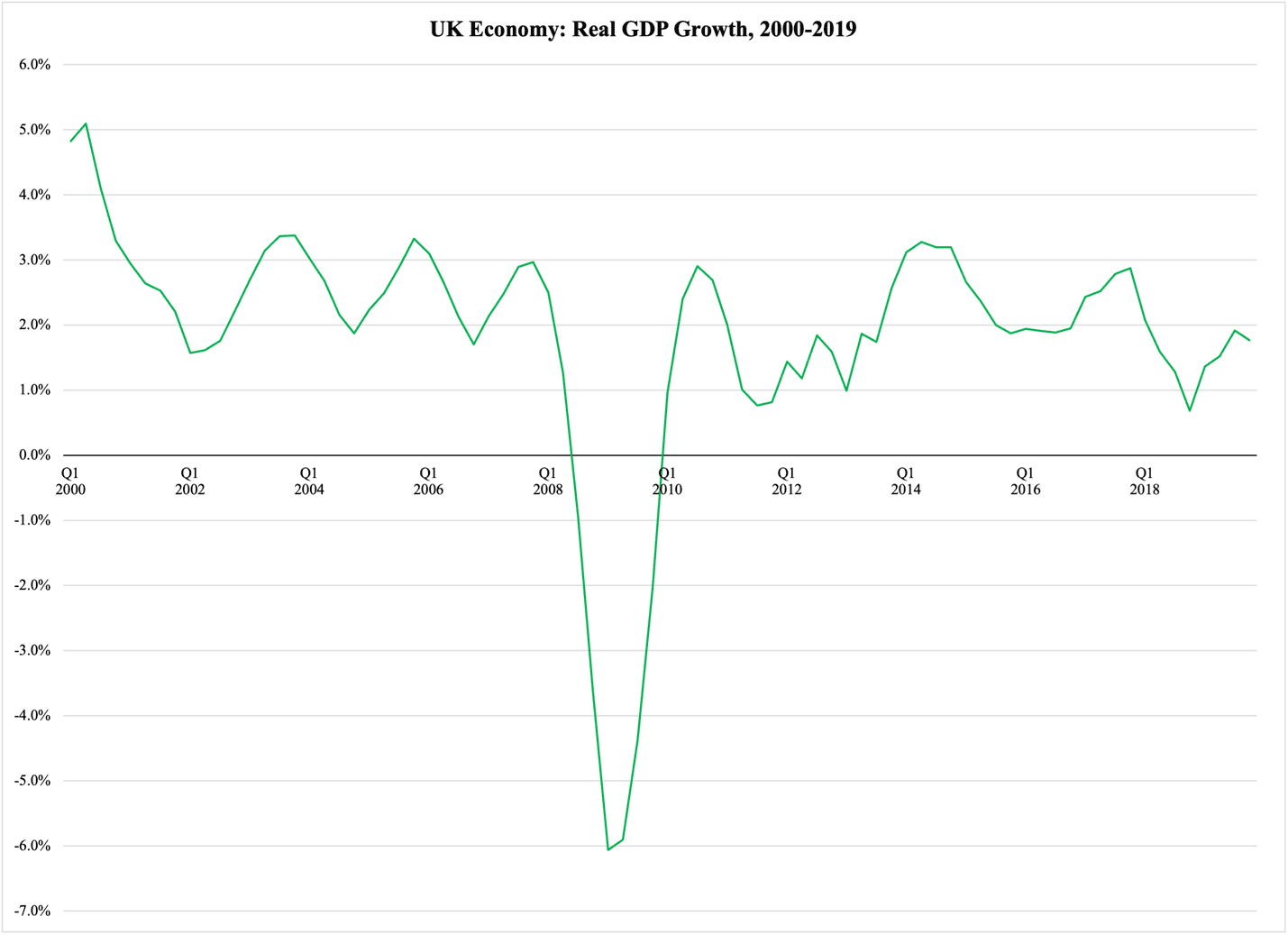

Then something happened. With the start of the new millennium, British GDP slowed down markedly. Figure 1b has the story:

Figure 1b

In the six-year period 2002-2007, British GDP expanded by 2.5% per year. Compare this to the 3.3% average for the six years from 1994 through 1999.

After the brief but serious so-called Great Recession, the economy recovered and stumbled back to growth. The years 2014-2019 were supposed to be a peak period for the business cycle, yet the British GDP only mustered 2.17% per year. This ranked the United Kingdom 20th in the EU at that time, well behind, e.g., Ireland (9.7% per year), Hungary (4.1%), and Spain (2.6%).

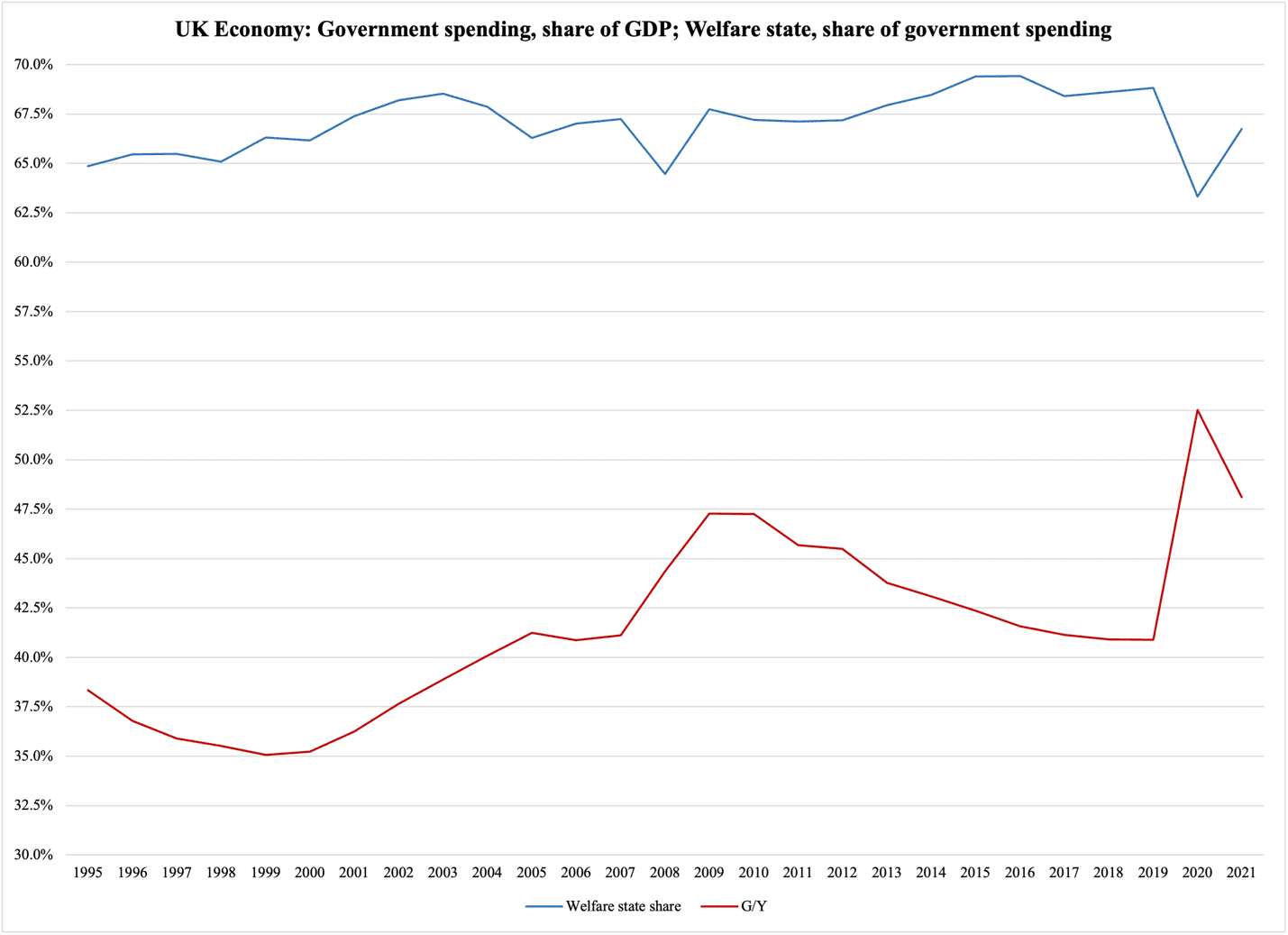

Although most of the EU did better than Britain while she was still a member, the decline in GDP growth is a problem that most European economies have. The reason is found in government spending: Figure 2 reports the outlays by the consolidated British government as share of GDP (red line) and the welfare-state share of those outlays (blue).

Figure 2

In 1995, when the time series in Figure 2 starts, government spending is 38.3% of GDP. It falls through the latter half of the decade, reaching 35.1% in 1999 and 35.2% in 2000. After that, it increases at a comparatively brisk pace until it flattens out in 2005-2007 at around 41%.

This increase is substantial enough to make it credible that government expansion has caused the slowdown of economic growth in Britain. In my book Industrial Poverty (Gower, 2014) I explain in detail (pp. 72-81) how the GDP growth rate of an economy shifts down permanently when government spending exceeds 40% of GDP.

The relationship is statistically compelling, but also logical from the viewpoint of economic theory: as government grows, it removes an increasing share of the economy from the realm of the free market and places it under the planned, non-market regime of government. Since the free market is the superior instrument for allocating resources with efficiency, it is also the superior instrument for economic growth; in a manner of speaking, when we can do more with less, we do a lot more.

Britain hit the critical 40% threshold in 2005-2007. Since then, government spending has remained solidly above that level. It does not help that, as indicated by the blue line in Figure 2, two-thirds of all that government spending goes toward welfare state functions. This means, bluntly, that British households to a high degree depend on government to make ends meet every month—a problem I analyzed in a separate article in October 2022.

Not all growth in government spending goes to the welfare state: during the pandemic, spending on so-called economic affairs—blunt Americans call it ‘corporate welfare’—more than doubled, from £75.3 billion to almost £175.2 billion. This spending has tapered off since then, but it is worth noting that even before the pandemic gave the British government an opportunity to suddenly dole out a lot more money to businesses, total government spending still claimed 41% of GDP.

It is difficult for governments within the EU to reduce the size of government, and Brussels is not making it easier for them. With Brexit, Britain had a golden opportunity to structurally redefine the role government plays in the economy. This opportunity was not lost because of the pandemic—on the contrary, it would have given those who were so inclined more time to piece together a good government reform plan.

That did not happen. Instead, the British government has cemented its role in the economy, to the detriment of the nation’s future prosperity. Currently, Britain is solidly in a state of economic stagnation, and although unemployment remains relatively low (4.2% in the second quarter of last year) the stagnant economy will inevitably kill jobs. Hopefully, this will inspire enough British policymakers to consider the opportunities for structural reform that opened up with Brexit.