A political fight is emerging in Germany over how to fund the rapid expansion of the nation’s defense budget. This fight coincides conspicuously with my two articles this week, where I analyzed the tensions around member-state fiscal commitments to NATO’s military capabilities. I pointed to the problems that America faces in writing a blank check to fund NATO. I also explained the trade-off between national defense and funding the welfare state.

The German debate goes straight to the core of the defense-funding issue that I have pointed to: the ideological choice between the military and the welfare state. Deutsche Welle, DW, reports:

German government defense experts have calculated that instead of the €52 billion currently earmarked for defense in the federal budget, more than double that amount—€108 billion—will be needed. … The budget for Labor and Social Affairs has been discussed as a likely place to make cuts to balance out defense spending.

As of 2021, the consolidated German public sector, which includes federal, state, and municipal governments as well as the social insurance funds, used 67.4% of all its money on the welfare state. It allocated 2.2% of the same resources to its military.

The latter number is a little bit below the 2.4% EU average, while the former exceeds the EU average of 66.3%. In other words, Germany is more slanted toward the welfare state than the EU as a whole, which makes the budget fight that DW reports on even more difficult than it will be in other countries.

On the German political scene, the social democrats have already come out strongly in defense of the welfare state. According to DW, Kevin Kühnert, the general secretary of the German social democrats, explains that Prime Minister Olaf Scholz, a social democrat, “has been misunderstood” by reporters who claim that Scholz wanted to prioritize the military over the welfare state:

In an interview with public broadcaster ARD, Kühnert said that social security and the territorial security of Germany, the EU and NATO belong together like “two inseparable sides of the same coin.”

To be clear, this fiscal debate is concerned solely with the budget of Germany’s federal government. While the states—the Länder—in Germany are independent jurisdictions, they are in practice deeply intertwined with the federal government. Responsibilities for social benefits and other government services are distributed between the federal and the state governments. A similar distribution model defines the allocation of tax revenue as well as the distribution of federal funds among the states and their programs.

The structural complexity of the German welfare state makes it difficult to reform its programs. Even if those changes are done at the federal level, they will reverberate through the states, either by reinforcing the ideological defense of existing programs at their level, or in the form of demands for compensatory spending increases. Or both.

Due in no small part to the institutional similarity between Germany and the United States, the unfolding ideological fight over Germany’s defense funding is a precursor to an American debate over the same issue. Perhaps without realizing it, Donald Trump precipitated that debate by explaining that there is a cap on how much money America can spend on its military. It did not take long, namely, for his most vocal opponent, former Congresswoman Liz Cheney, to express her view.

By refusing to make fiscal choices as part of her argument for a U.S. blank-check NATO commitment, Cheney effectively sides with the German social democrats and their ‘both matters’ approach. The next question for her and for all American politicians who share her view is whether or not they are willing to ask America’s taxpayers to fill NATO’s funding gap. If America is going to militarily guarantee the safety of its NATO allies on a ‘no matter what’ basis, and if those who advocate this doctrine are not willing to seek compensatory cuts in other spending programs, then their only option is higher taxes. More debt is out of the question.

The next problem is that higher federal taxes would be heavily concentrated to a small group of taxpayers. To see just how concentrated this bid for higher taxes would be, let us dive into some tax and income data from the Internal Revenue Service.

About 80% of all federal tax revenue comes from taxes on personal income. Those taxes are split about evenly between personal income taxes and social security taxes, but there is nothing even about how the tax burden itself is distributed. In 2021, the latest year for which the Internal Revenue Service publishes data on federal tax payments, taxpayers who made up to $100,000 per year paid 11.9% of all personal federal taxes.

This means, of course, that taxpayers who made more than $100,000 per year paid 88.1% of all those taxes. The 0.8% of all taxpayers who earned more than $500,000 paid 51.2% of all personal federal taxes. Meanwhile, the 53% who made less than $50,000 were responsible for 2.9% of all taxes paid. Any increase in federal income taxes will most likely distribute the additional tax burden along the same pattern.

But is this not fair? If we have to raise income taxes, should we not do that on those who can pay the most?

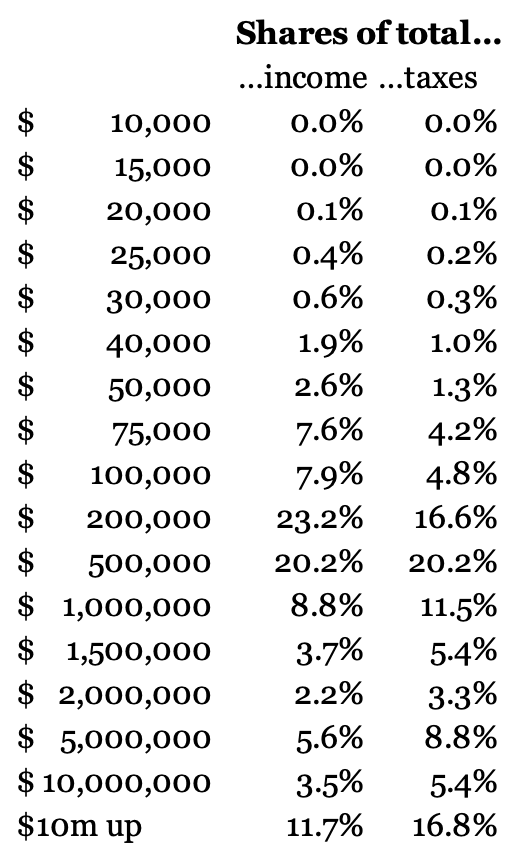

The plain answer is ‘no’: even though the half-percent of people with more than $1 million in taxable income do indeed make a lot of money, their tax burden is already heavily unfair. To see why, consider the numbers in Table 1 below:

The left column reports the share of total taxable income that each income group makes; e.g., those who make between $50,000 and $75,000 per year earn 7.6% of total taxable income;

The right column reports the share of total personal federal taxes that are paid by each income group; e.g., those with an income of $50-75,000 per year paid 4.2% of all personal federal taxes.

Table 1

As the table shows, most income groups pay a smaller share of total taxes than their income share would merit. This distribution is primarily the result of a tax code that steeply raises the tax rate as the taxpayer’s income rises.

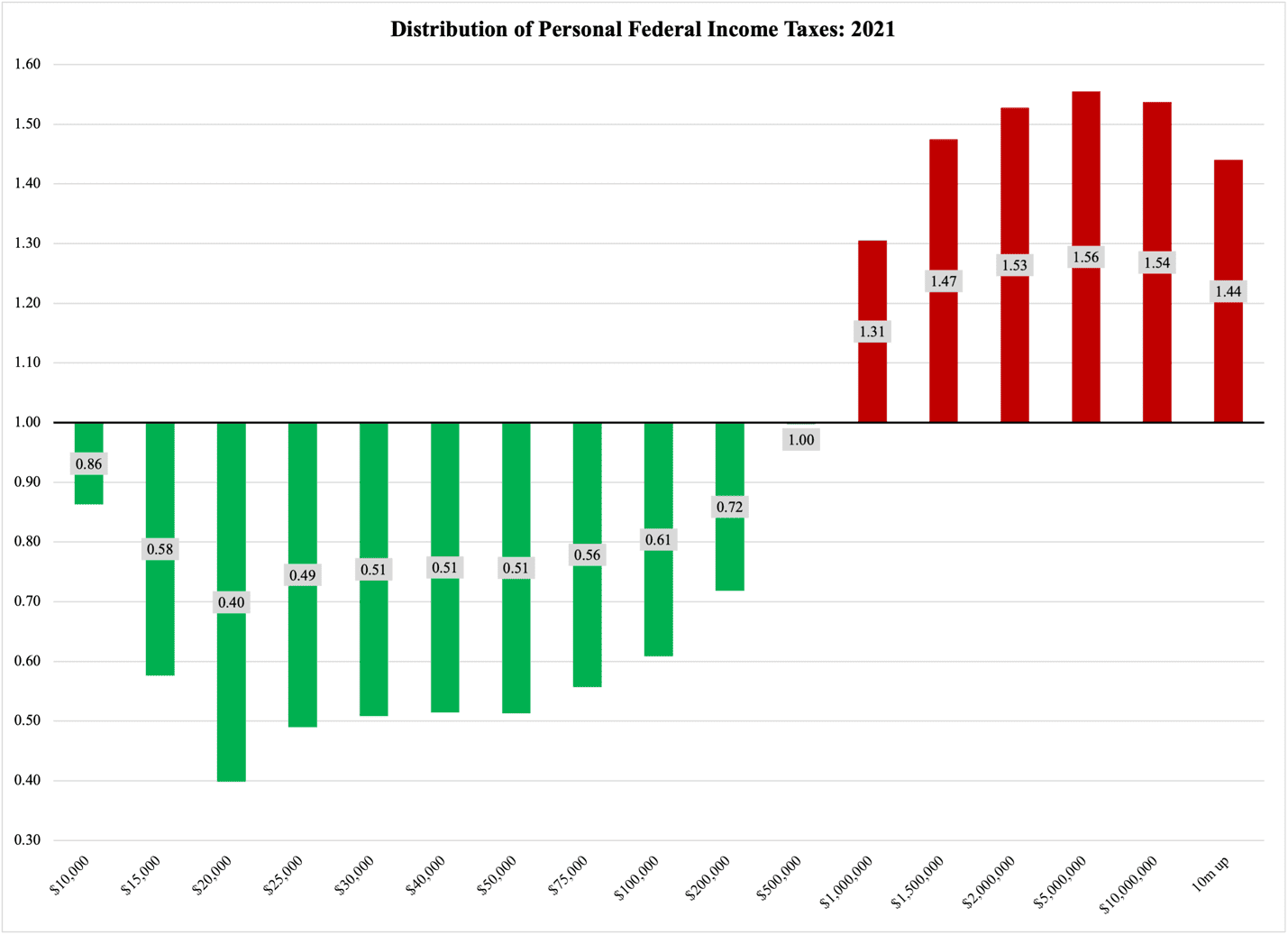

If we divide the tax share by the income share, we get a good picture of the ‘fairness’ of the federal tax code. Figure 1 shows that households making more than $500,000 per year already pay more taxes than their incomes merit: taxpayers with $500,000 to $1,000,000 in annual income $1.31 in taxes for every $1.00 that would be a fair tax burden. In short: they are overtaxed by 31%.

By contrast, taxpayers making $75-100,000 per year pay only 61 cents for every $1.00 they should pay under a fair tax system:

Figure 1

In short,

The distributional pattern of the federal tax burden is openly ideological: it says that those with high incomes have an ideological responsibility to pay for the federal government. Two-thirds of the federal government’s expenses go toward the welfare state; its benefits, in turn, go to those who have incomes low enough to fall into the ‘green’ columns above. Therefore, America’s ‘rich’ subsidize America’s ‘poor.’

The funding of the U.S. military follows the same pattern. Given that personal federal taxes provide 80% of total federal tax revenue, anyone proposing higher taxes to pay for, at least, the $91 billion that would close the currently estimated NATO funding gap, would have to ask the top-0.8% of America’s income earners to pay about $37.3 billion more in income taxes.

As much as the blank-check NATO funding argument is understandable from a military and security perspective, we cannot simply ignore the fiscal realities of government finances. The current debate in Germany is a stellar example of this, and a lesson to be learned for America’s political leaders, regardless of which side of this issue they are on.