With inflation coming down globally, analysts, pundits, and even some politicians are showing impatience with central banks that refuse to cut interest rates.

That impatience will continue to simmer for some time. For now, the leading central banks in Europe and North America have decided to take a wait-and-see approach to rate cuts. The exception is Hungary’s Magyar Nemzeti Bank which earlier this week lowered its policy-setting rate from 10.75% to a flat 10%.

In a show of independence, the MNB demonstrated why Hungary has made the right decision in not joining the euro zone. The country’s monetary authority can tailor its policy strictly to the needs of the Hungarian economy.

In addition to exercising its independence, the MNB also responded to the sharp drop in inflation in Hungary. After leading Europe with inflation rates north of 20%, Hungary is now in the European mainstream with a rate of 5.5%; without further disturbances, the country could reach price stability in the second quarter this year.

As mentioned, not all central banks are ready to cut their rates. There is a general worry that inflation will either remain elevated or rebound again. The Bank of Canada, BoC, held its policy meeting on January 24th and decided to keep its lead Bank Rate unchanged at 5.25%. This was a good decision, given that Canada’s GDP grew by a paltry inflation-adjusted 1.8% in the first quarter of 2023, by 1.2% in Q2, 0.5% in Q3, and by 1% in Q4.

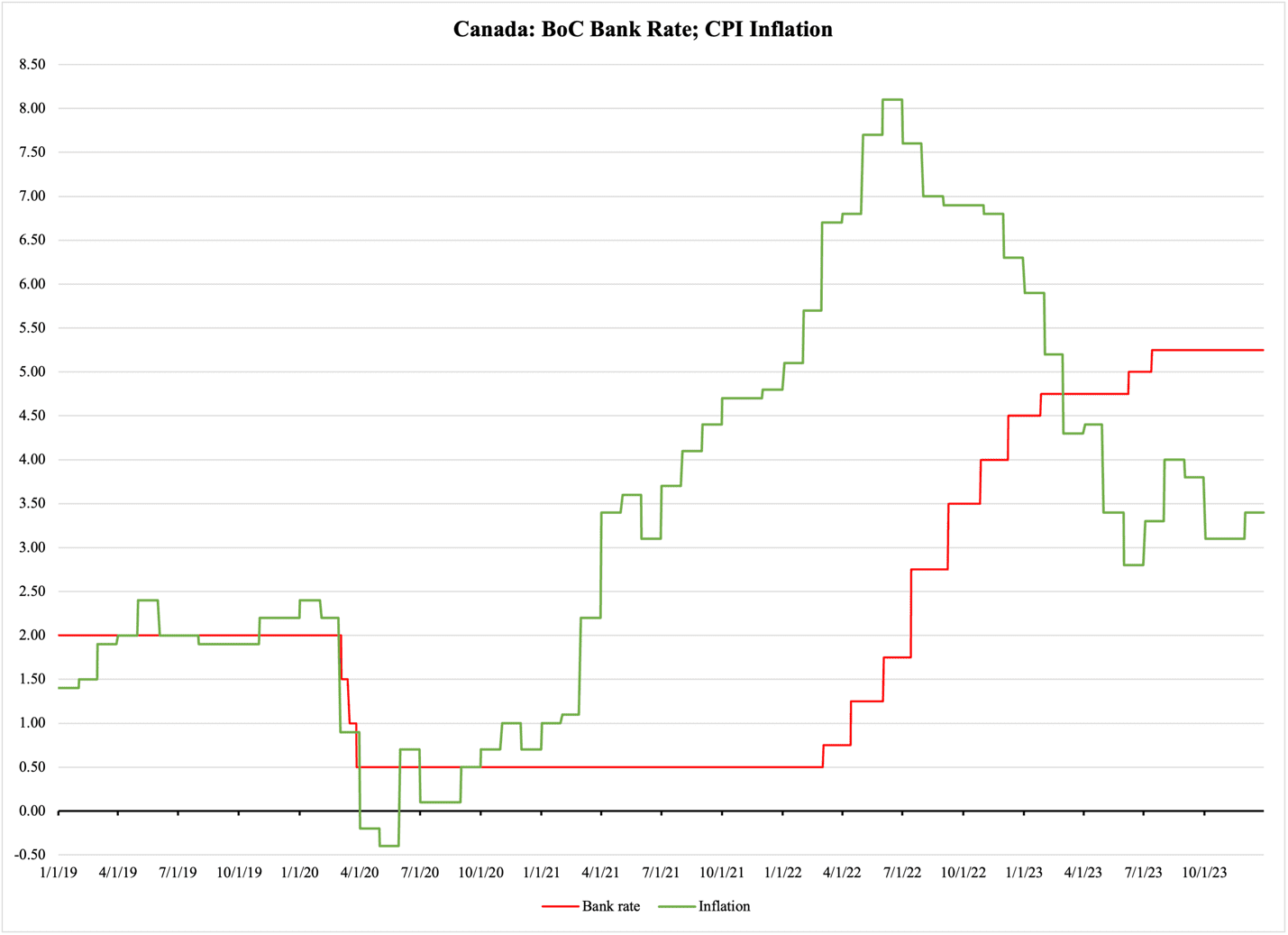

According to the BoC’s policy statement, the Canadian economy “will likely remain close to zero [growth] through the first quarter of 2024.” At the same time, Canada is still dealing with high inflation. Figure 1 compares the BoC’s “Total CPI” inflation measure with their policy-setting Bank Rate:

Figure 1

The BoC willfully participated in the international monetary stimulus during the pandemic in 2020. It irresponsibly maintained its policy rate at 0.5% into early 2022, when inflation topped 8%; only then did it shift to a more monetarily conservative policy regime. When it did, inflation came down fairly quickly, but it has been stalled in the 3-4% range since last summer.

It is worth noting that the persistence of inflation coincides with the Bank of Canada ending its rate hikes and sticking to 5.25%. They likely did this in response to the weak performance of the Canadian economy, which explains the bank’s wait-and-see approach. However, that policy stance is not sustainable over the long term. It is a temporary compromise between the need for lower rates to get the economy going and higher rates to kill off inflation.

The recovery they are hoping for later this year will not happen if inflation and interest rates remain elevated; at the same time, the only way to bring the interest rate down is to curb inflation—which may require temporarily higher interest rates.

A day after the Canadian central bank’s wait-and-see decision on its interest rate, the European Central Bank likewise decided to wait and see:

The Governing Council today decided to keep the three key ECB interest rates unchanged. … Aside from an energy-related upward base effect on heading inflation, the declining trend in underlying inflation has continued, and the past interest rate increases keep being transmitted forcefully into financing conditions. Tight financing conditions are dampening demand, and this is helping push down inflation.

At a 4.5% average, the ECB’s three interest rates are high enough to have the sought-after dampening effect on macroeconomic activity, but not high enough to have any significant effect on inflation, should it rebound. There is no immediate sign of that; the euro-zone inflation rate fell from 4.3% to 2.9% in October, marking the first month of sub-3% inflation since July 2021. After dropping to 2.4% in November, the inflation rate returned to 2.9% in December.

It is unlikely that inflation will again rise above 3%; the main question for the ECB is whether or not they can reach their 2% inflation target without raising rates. While this may be necessary in Canada, I do not see the same need in the euro zone. As noted above, the Canadian economy is already at a standstill, while the euro zone is on its way into a recession.

The only reason that the ECB should raise rates at this time is to curb attempts by member states to let their budget deficits expand in the hopes that the central bank would return to buying sovereign debt with newly printed money.

On January 31st, it was America’s time to wait and see. The Federal Reserve’s Open Market Committee, FOMC, went against the public calls for a rate cut. They kept their federal funds rate unchanged at a target rate of 5.33% (which technically is the average of its policy range of 5.25-5.5%) and motivated it accordingly:

Recent indicators suggest that economic activity has been expanding at a solid pace. Job gains have moderated since early last year but remain strong, and the unemployment rate has remained low. Inflation has eased over the past year but remains elevated.

With hints of a recession emerging, it is likely that the Fed will cut its rate at its meeting on March 19th. I hope they don’t, because that would encourage Congress to continue recklessly using budget deficits as their prime revenue source. However, the fiscal balance is not a policy priority for the Federal Reserve.

If the Fed does cut its funds rate in March, the Bank of England is likely to follow suit. On February 1st they joined the wait-and-see club of central banks: their Monetary Policy Committee decided “by a majority of 6-3 to maintain Bank Rate at 5.25%.”

The only reason for the Bank of England not to follow the Fed in a rate cut would be that British inflation remains elevated. Per the report from the Monetary Policy Committee meeting, of the three that voted against keeping the Bank Rate unchanged, two wanted to actually raise the rate. These were prudent votes, given that Britain does not seem to be able to get inflation under control.

The Swedish Riksbank, announcing its most recent policy decision on February 1st, also took a wait-and-see approach to monetary policy:

The Riksbank’s rate increases have contributed to a fall in the earlier high inflation. However, when energy prices are excluded, inflation is still too high and there is a risk of setbacks. The Executive Board has decided to leave the repo rate unchanged at 4 percent.

They go on to claim that “contractionary monetary policy is still needed” so long as inflation is not “close to the target” that the central bank has set. Technically, maintaining the policy-setting interest rate unchanged is not a contractionary policy measure—it is neither contractionary nor expansionary.

That point aside, though, it is worth noting that while the ECB is satisfied with inflation falling despite a spike in energy prices, the same prices play the opposite role in the Swedish economy. This is yet another example of why it is essential for countries to maintain their monetary independence: if Sweden had joined the euro, the monetary policy that benefits the euro zone as a whole—or just its largest members—is not the policy that would benefit the Swedish economy.

The fact that they happen to be the same at this point is more of a sign of how they follow the Federal Reserve than anything else. With that said, as Hungary demonstrates, monetary independence can be a useful tool for a country’s economic-policy makers. This is something to think about for those in Sweden who want the country to join the euro.