Last week, Congress reached a spending deal that will avoid a shutdown of federal government agencies. The news, which made the top of the news cycle, included a passage about how this deal complies with a previous agreement to curb growth in the U.S. government’s debt.

We have good reasons to be skeptical about any news that alludes to any limitations of the federal government’s borrowing. The deficit hole in the federal budget is now of such proportions that Congress cannot address it unless it puts all other issues aside for an extended period of time.

In short: only the declaration of a fiscal national emergency, suspending the normal functions of our government, would make a difference here. We should be thankful that no branch of the federal government has such emergency powers, but we should also be able to expect that in lieu of such powers, Congress would step in and assume responsibility for its own finances.

Such initiatives are sorely needed. From October 1st, when the U.S. government started its 2024 fiscal year, to the last day of December, the government’s debt increased by $559.3 billion.

A quarter of the fiscal year has already passed (the fiscal year being the year for which Congress budgets annually), and this brisk pace of debt growth shows no signs of slowing down. If nothing radical happens, when we close the books on the whole of FY 2024 on September 30th, the debt will have grown by well over $2 trillion.

Only a few short years ago, it was sensational if the debt even grew by $1 trillion per year.

In the 2023 fiscal year, from October 2022 through September 2023, the federal debt grew by more than $2.2 trillion, or $2,238.4 billion to be exact. If we make the simple assumption that the $559.3 billion for the first quarter of FY 2024 reflects the pace at which the debt will continue to grow throughout the rest of the fiscal year, then the total tally will be $2,237.2 billion.

This number is big enough as it is, but the story gets worse. The federal government spends almost $1.6 trillion per quarter. Suppose the most recent figure, the $1,594.5 billion in July-September, i.e., the third quarter of last year, was also the level of spending in the fourth quarter.

Since the fourth quarter of the calendar year 2023 is also the first quarter of the 2024 fiscal year, we can now simply divide the $559.3 billion in new debt with the federal government’s outlays.

What do we find? Congress is borrowing 35 cents of every dollar it spends.

As if that number was not scary enough, a breakdown of the federal government’s revenue sources tells us that borrowed money is now their single largest income source.

Let us go back to the third quarter of 2023, i.e., the period July-September. This was also the fourth and last quarter of the 2023 fiscal year. During that quarter, the federal government borrowed $835 billion. Its tax revenue sources were as follows:

With $559.3 billion borrowed in the period October through December, there is a good chance that the same will be true also for the most recent quarter. It is also likely that this will continue into 2024: as I explained on December 29th, we should not expect much effort from Congress to address this runaway debt crisis. The most they will accomplish, I said, is to try “to remove the debt crisis from the election cycle” by appointing an essentially meaningless debt commission.

They might not even get around to that. Going back to the news about the recent spending deal to avoid a government shutdown, NBC reports that “a deal Sunday on how much the U.S. government will spend in the new year” keeps federal government agencies open until January 19th.

With some more effort, Congress can keep the U.S. government operating a few more weeks after that.

The broader picture emerging from this is quite grim: while the government of the United States is now relying on new debt to provide about 35 percent of its revenue, and borrowed money is its largest source of revenue, all that Congress can muster is a deal to spend money a few weeks at a time.

With this fiscal attention span in Congress, it is impossible to see how they could ever dedicate any kind of productive attention to the budget deficit. On the contrary, it seems as though no bad news can get through to them, not even the much-announced threshold for annual debt costs that the U.S. government passed in the fall. On November 7th, Bloomberg.com reported that this cost had reached $1 trillion.

My own debt-cost model puts that threshold at November 13th, but regardless of the exact date, it is a fact that Congress now must pay out at least $1 trillion annually just to honor their debt obligations. This also means that almost half of the money they borrow goes right back to their creditors in the form of interest payments.

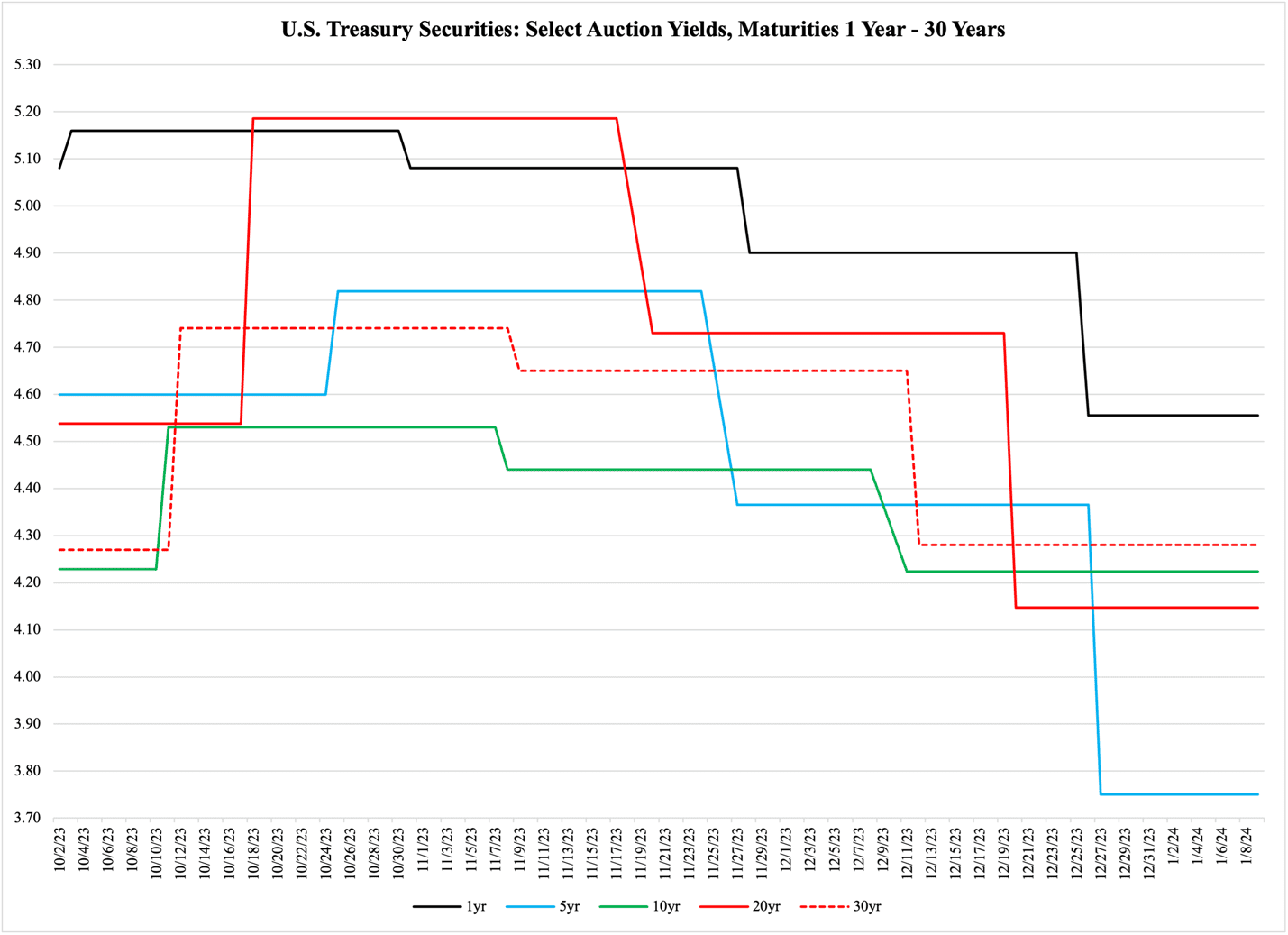

The only good news here is that interest rates have been falling recently. With any luck, the upward pressure on the debt cost will ease as we move further into 2024. As Figure 1 reports, interest rates on new U.S. debt, a.k.a., auction yields, have been falling in the past several weeks, at least for the Treasury securities that are auctioned monthly. Figure 1 offers a sample:

Figure 1

Yields on shorter-term debt, which is auctioned weekly, have not been falling much (the exception being the 26-week bill). This tells us that the decline in long-term yield is not the result of investor confidence in the U.S. government’s ability to manage its finances. Instead, the decline at auctions for longer-term debt is the result of an inflow of investor money to secure good yields.

It is widely expected that the Federal Reserve will cut its interest rates later in the new year. With those cuts, yields on U.S. debt would decline as well; by buying long-term debt now, investors can secure a 4-5% annual return for years to come.

Since yields remain high on short-term debt, the market for U.S. Treasury securities maintains a so-called inverted yield curve: it pays more for investors to own short-term debt than long-term debt. When inflation is high, this phenomenon is normally a sign of inflationary expectations. However, the fact that the inverted curve remains even as inflation has come down to manageable levels indicates that investors distrust the U.S. government over the short term. While they expect long-term debt obligations to be safe, they are worried about what will happen to the U.S. debt market over the shorter term.

With new debt being the primary revenue source for the federal government, investors have good reasons to worry.