The European Central Bank is holding its next policy meeting on June 6th, and speculations are already abundant on whether or not the bank will cut its interest rates at that meeting.

A lot speaks in favor of a rate cut, especially statements like this one, reported by EUBusiness.com on May 20th:

Martins Kazaks, a policy maker at the European Central Bank (ECB), stated this morning that it is “most likely” the bank will begin its rate-cutting cycle in June.

The EUBusiness article also explained that there “seems to be a consensus” at the ECB around the prediction that inflation is on its way down to 2%. This is the inflation rate which the ECB and many other central banks consider a prudent balance point.

A look at inflation data suggests that this return to 2% is more wishful thinking than anything else. As a preamble to those numbers, EUBusiness quotes Isabel Schnabel, a member of the ECB’s policy-setting council. She expresses caution over “cutting rates prematurely” and thereby causing a rebound in inflation.

I do hope that the ECB takes Schnabel’s words seriously. Although euro zone inflation has come down substantially from its peak at 10.6% in October 2022, there are indications that it has bottomed out before it reaches 2%. In April 2023, the euro zone inflation rate was 7%; it ticked down to 2.8% in January, 2.6% in February, and 2.4% in March.

The April 2024 inflation rate was also 2.4%. That in itself is not a sign that inflation has stalled, but there are plenty of signs from around the euro zone that inflation will fall no further. Most important among those signs is the inflation rebound in Belgium and the Netherlands:

Belgium is not the only country where inflation has bounced back above 4%. Croatia, the most recent member of the euro zone, suffered from 12.5-13% inflation from July 2022 through January 2023—the month they joined the currency area. Since then, inflation has come down, but sluggishly: after reaching 8% in July 2023 it crept below 5% as recently as in January. Since then, it has been averaging 4.8%, with no signs of abating further.

Austria and Spain are still at 3.4% inflation, Estonia at 3.1%, and Luxembourg, Poland, and Slovenia are all at 3%. Of these, only Slovenia shows a downward trend.

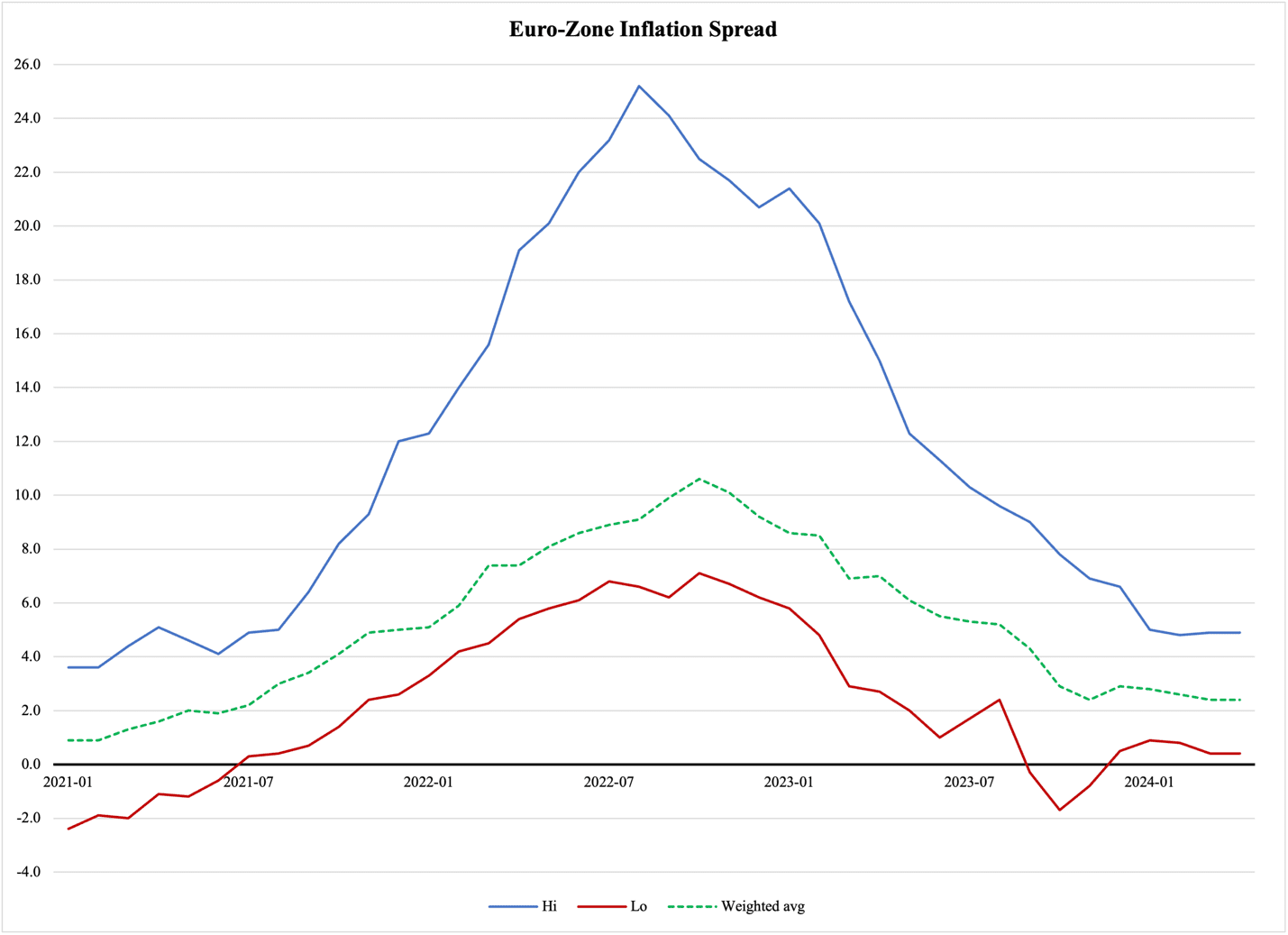

The variety of inflationary trends and rates is a major problem for the ECB. To see just how big it is, consider Figure 1, which reports the highest (blue) and the lowest (red) inflation rates among all euro zone members since 2021. The dashed green line represents the weighted average inflation rate for the euro zone as a whole:

Figure 1

When making monetary policy, the European Central Bank is inevitably drawn to the weighted inflation average for the currency area. This means that when tightening the money supply to end an eruption of monetary inflation, the size and pace of their policy moves will be suitable for the countries at the lower end of the inflation spectrum. The ones with higher inflation rates will, at least to some degree, be left to fend for themselves.

In terms of cutting interest rates in June, the ECB will once again have to choose between a policy close to the mainstream and paying due attention to the exceptions. With two economies experiencing a rebound in inflation and six economies exhibiting price hikes at more than 3% per year, the ECB faces the risk that it helps reignite inflation, even if limited to peripheries of the currency area.

The greatest substantive risk is that interest rates go negative while the activity level is high in the high-inflation countries. Looking at Belgium and the Netherlands, where inflation is rebounding, unemployment in March was 5.5% and 3.7% respectively. These levels are stable, suggesting that both the Belgian and the Dutch economies could be ripe for stronger economic activity.

A rate cut from the ECB will certainly help with this, but it can also in short order bring back inflation. This is certainly a risk in the Netherlands, where unemployment did not exceed 5.5% even at the depth of the pandemic-related economic shutdown.

Other euro zone countries are at the opposite end of the scale. Finland has seen its unemployment rise from an average of 6.8% last fall to 9% in March. The three Baltic states are doing almost as poorly: Estonian unemployment is 7.9%, up from just over 6% in the fall; in Latvia, the jobless rate has gone from 6.3% to 7.1% in six months; in Lithuania, it has risen from 6.1% to 8.2% in the same period.

At 3.4%, unemployment in Germany is a bit less than half of what it is in France. Meanwhile, Greece and Spain represent the real outliers, with 10.5% and 12.2%, respectively—and the rate is rising in Spain.

The best one can say about the eurozone economy is that it is a mosaic of economic differences. That may make for an interesting object to study for us economists, but it does not help the ECB in making its policy decision. While under political pressure to cut rates, the central bank of the euro zone is faced with an impossible task:

Unfortunately, given the statements from ECB officials about a coming interest rate cut, it is likely going to happen. With that said, for the reasons discussed here I would expect it to be more symbolic in nature than driven by policy substance. Such a move will help preserve the macroeconomic status quo for currency area members, but it will not help anyone in particular make any significant economic progress.

The question of an ECB rate cut is not only an illustration of why the euro itself is a less-than-spectacular invention; it is also a reminder for euro-aspiring countries like Bulgaria and Sweden to think twice before giving up their national currencies.