One of the principles built into the European Union, the Stability and Growth Pact, was intended to secure sound public finances among the several member states. With clear fiscal rules, the Pact was supposed to cap member-state budget deficits at 3% of GDP and consolidated government debt at no more than 60% of GDP.

If there is one of the EU’s founding principles that has failed, this is it. Of the current 27 member states, only one—Sweden—has never broken either of the two fiscal rules; a clear majority, 17 of them, have broken both rules at least once, and 6 countries have broken both rules more than half the time since 2002.

The worst culprit among them all is France. This is relevant, for one important reason: as our reporter Zoltán Kottász explained on June 17th,

The European Union is ready to punish France if Marine Le Pen’s nationalist-sovereignist National Rally … wins the upcoming French parliamentary elections

The punishment would consist of strict enforcement of the Stability and Growth Pact and the ultimate exaction of a fine as punishment.

Adding details, Politico reports:

France is among a dozen countries that will receive a red flag next week for breaching the bloc’s deficit threshold. This will put them into what’s called an “excessive deficit procedure,” which requires governments to take action to rein their spending

Technically, it is up to the targeted member state how they go about balancing their budget: by cutting spending, raising taxes, or a combination of the two. The main point, though, is that the European Commission appears to have woken up from a long fiscal slumber during which the Stability and Growth Pact was not enforced.

There are two curious details about the fact that the Commission has suddenly decided to enforce the Pact. The first is the timing: the European economy may have dodged a deep recession, but it is stuck in a state of perennial economic stagnation. Strict enforcement of the Stability and Growth Pact would only lead to a tightening of macroeconomic activity; if enforced at the level indicated in the Politico article, it could in fact nudge the EU as a whole into a recession.

Secondly, in his article for The European Conservative, Kottász highlights how the Commission is readying a clampdown on France with explicit reference to the possibility that Rassemblement National wins the two-part parliamentary election. Several sources cited by both Kottász and Politico suggest widespread worry among commentators and analysts that the RN would be even more fiscally frivolous than the current and previous French governments have been.

Given the fiscal track record that France has, it hardly matters whether or not a new government led by Marine LePen would increase the budget deficit. As mentioned, no other country in the European Union has breached the Stability and Growth Pact with more persistence than France.

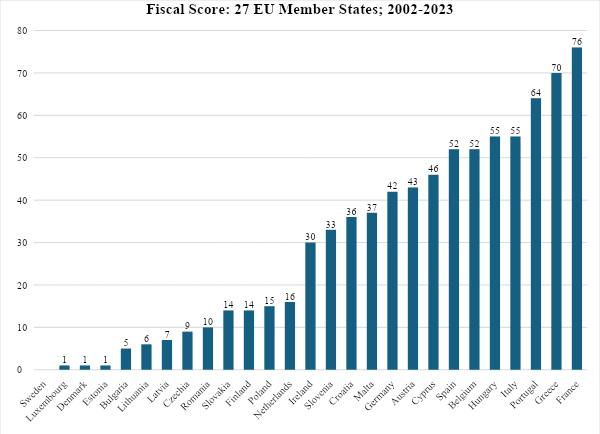

At the same time, disregard for the Stability and Growth Pact has been widespread across the EU for so long that it is practically impossible to imagine a shift among member states to compliance. To measure the degree of disregard or compliance, I developed a simple index of the fiscal status of all the current 27 member states. It covers the period 2002-2023, in other words, 22 years, and consists of three parts:

Suppose Sweden had a debt of 64% of GDP in 2014 and 2015, and a deficit of 5% of GDP in 2015 and 2016. It gets 1 point each for its debt in 2014 and in 2015, for a total of 2 points. It also gets 1 point each for the deficits in 2015 and 2016. The country now has 4 points. In addition, since it broke both rules in 2015, it gets another 2 points, for a total of 6 points.

The idea behind the extra points for breaking both rules is the presumption that if each fiscal rule in the Stability and Growth Pact is meaningful as an instrument for fiscal containment, then breaching both at the same time must be particularly bad from a macroeconomic viewpoint. I would personally (based on my long career as a Ph.D. economist) suggest that these rules are without much macroeconomic merit, but that is not how the EU Commission sees it. They have suddenly come to believe that enforcing them is essential for the economic future of the European Union, and since they see it that way—and show heightened interest in clamping down on France under a future LePen government—my simple index is designed to reflect their reasoning.

Before we get to the results of the indexing, let me add one more detail. I have included all 27 current EU member states, for the entire period 2002-2023. Not all of them were member states for that period, but I have included them anyway: they all aspired to become members, and as such, or as formal candidates for membership, they were forced to align their fiscal policies with the Stability and Growth Pact. Therefore, the Pact has de facto applied to them for the entirety of the period studied.

With that said, Figure 1 has the scores. Only one country, Sweden, has complied with the Pact on both the debt and deficit accounts, every single one of the 22 years. Three other countries have violated it once, either by running an excessive deficit or an excessive debt in one single year.

As for the rest, they are a varying mess of fiscal frivolity, irresponsibility, or downright recklessness:

Figure 1

In addition to Sweden, nine countries have never been in double breach. i.e., violated both the deficit and the debt rule in the same year: Bulgaria, Czechia, Denmark, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Poland, and Romania. All their violations were strictly limited to excessive deficits; at no point did any of these 10 countries exceed the 60% debt threshold.

However, this does not mean that they are all shining jewels of fiscal responsibility: with the exception of Sweden, they all violated the deficit rule at some point. The three worst offenders were Czechia (9 years), Romania (10), and Poland (15).

A majority, 14 countries, have violated the 60% debt limit for at least half of the 22 years covered here. Six of them violated it every single year: Austria, Belgium, France, Greece, Italy, and Portugal. Interestingly, in this group, we also find the two worst offenders on the deficit side: Greece with 16 years of bigger-than-3% deficits, and France with 18.

Other countries with excessive deficits for half or more of the 22-year period are Cyprus, Italy, and Slovakia (11 years), Croatia (12), Hungary and Portugal (14), and Poland (15).

All in all, over the past 20+ years there have been plenty of opportunities for the EU to enforce its Stability and Growth Pact against its member states, but only a very small group of them have actually been on the receiving end of it. Therefore, it is difficult to take the Commission seriously when they are now trying to shift toward actual enforcement of the Pact.

Moreover, if they do indeed want to come across as more concerned about fiscal discipline, they cannot start by singling out a potential future government in one country and declare that they are going to make an example of them. The political ramifications of such behavior notwithstanding, it will not help make Europe more fiscally disciplined.