Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni

Photo: Elekes Andor, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

As the EU approaches its June parliamentary election, opinion polls point to strongly growing support for EU-skeptic parties. Therefore, logic would suggest that the political top brass in Brussels should be extra careful not to behave in ways that drive even more voters into the arms of those parties.

Unfortunately, logic is in short supply in the European capital. On April 3rd, Euractiv.com reported that the European Commission is readying actions against at least one member state in a move that would be certain to raise the temperature on the EU-skeptic side of the political aisle:

During a Wednesday hearing on the reform of European economic governance, Italian Economy Minister Giancarlo Giorgetti (Lega/ID) said the European Commission will recommend the Council of the EU to open an excessive deficit procedure against Italy, along with several other countries.

According to Euractiv, this move by the Commission is based on “the Stability and Growth Pact” which, the publication suggests, was “introduced following the pandemic.”

This is factually incorrect. The Stability and Growth Pact has been part of the constitution of the European Union ever since its first draft was ratified in Maastricht in 1992. This is a detail, but an important one: it means that the SGP has been used before by the EU against its member states, and that its application in the past is a good source of information on what we may expect this time.

As of April 8th, the European Commission had not made any official announcements regarding new excessive deficit procedures. Therefore, it is not immediately possible to verify if Italy is the only country targeted, and if not, what other countries are included. Other media reports on the matter deliver largely the same story, which means that we can at least look at Italy as the target of new deficit procedures. However, given the mention that other countries may be included, there is little doubt that we will have reasons to return to this issue in the near future.

The timing of the Commission’s excessive deficit procedure against Italy is mysterious, to say the least. To see why, let us delve into the formal reason why they would go ahead with this procedure.

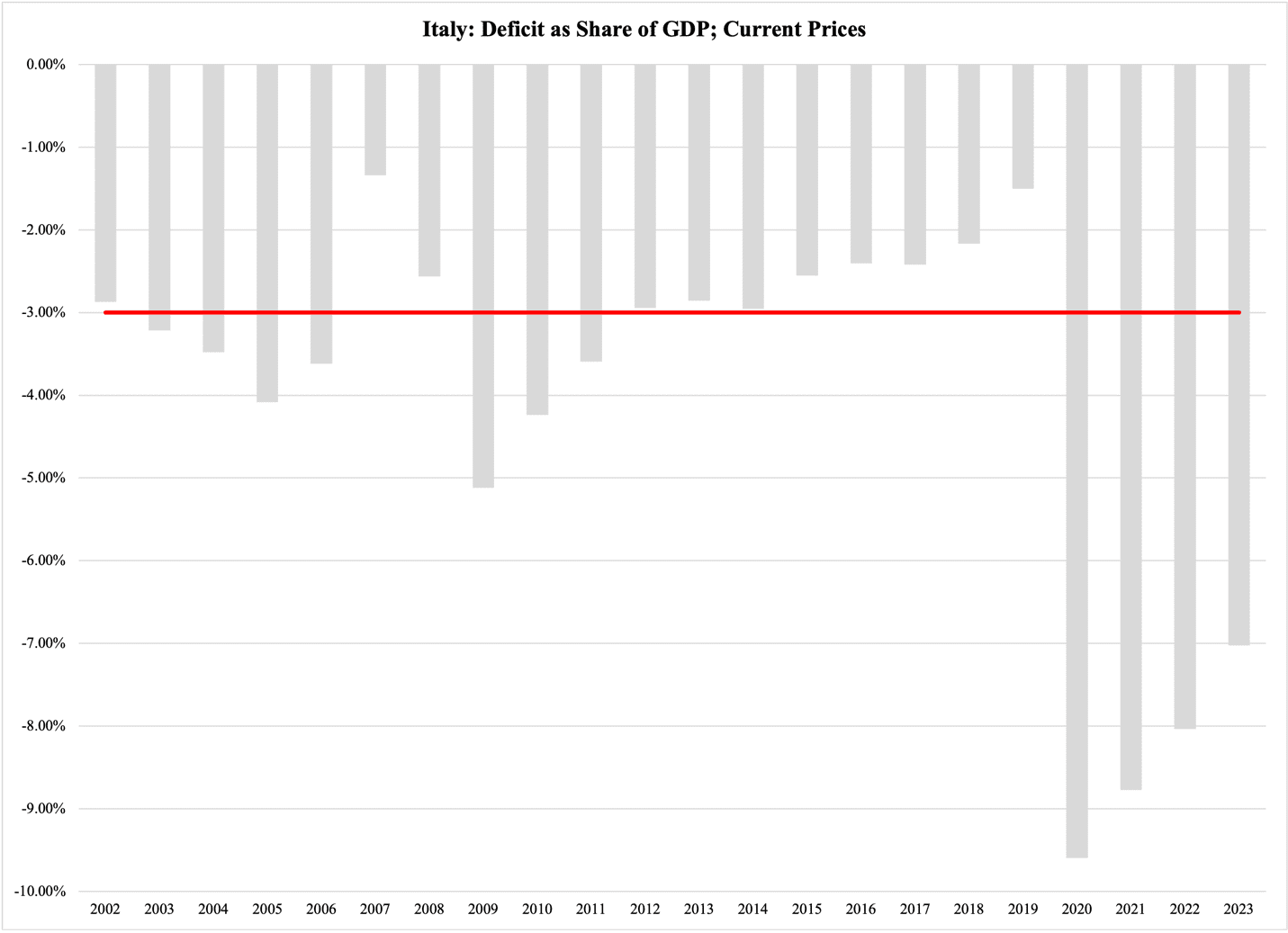

Italy has a fiscal deficit in its consolidated government that exceeds 3% of GDP. The Stability and Growth Pact bans member states from running budget deficits in excess of this threshold. Strictly speaking, the Commission can start this invasive procedure already after one year’s breach of the 3% rule, but in practice, the breach happens over an extended period of time before the Commission reacts.

From a strictly formal viewpoint, Italy is an easy target for the Commission. The country has had a deficit in its consolidated government finances every year since at least 2002. However, from 2012 through 2019, those deficits were below the 3% threshold, and they got smaller over time. Curiously, back in 2018, the European Commission also announced a deficit-procedure inquiry against Italy. Back then, it did not yield much in terms of policy substance; hopefully, that will happen this time as well.

The artificial economic shutdown during the 2020 pandemic drastically increased the deficit to 9.6% of GDP in 2020 but, after the economy opened up, the deficit fell to 8.8% in 2021 and 8.4% in 2022. Eurostat has not yet published a full year’s worth of public finance data for 2023, but according to the Italian government’s own statistics bureau, Istat, its net borrowing need for 2023 amounts to 7.2% of GDP.

This last number is important, as it shows a downward trend in the Italian government’s budget shortfall. We should keep in mind that Istat reports net borrowing, which is marginally different from a budget deficit. This number, 8.6% of GDP for 2022, was a smidge higher than the Eurostat number for the same year. However, since the difference is only 0.2 percentage points, we disregard it here and assume, simply, that the deficit as reported under Eurostat’s definition will be equal to Istat’s net borrowing.

If we add a 7.2% GDP deficit for last year, we have a steady downward trend in the Italian budget shortfall:

Figure 1

This trend raises the question of why the European Commission has decided to take action based on the Stability and Growth Pact. If we extrapolate the trend, the Italian government should be below 3% of GDP by the end of 2026. That does not mean Italy will balance its public finances, but the Commission is only interested in seeing the deficit decline below the 3% threshold. Therefore, its exhibition of impatience is curious at best, worrisome at worst.

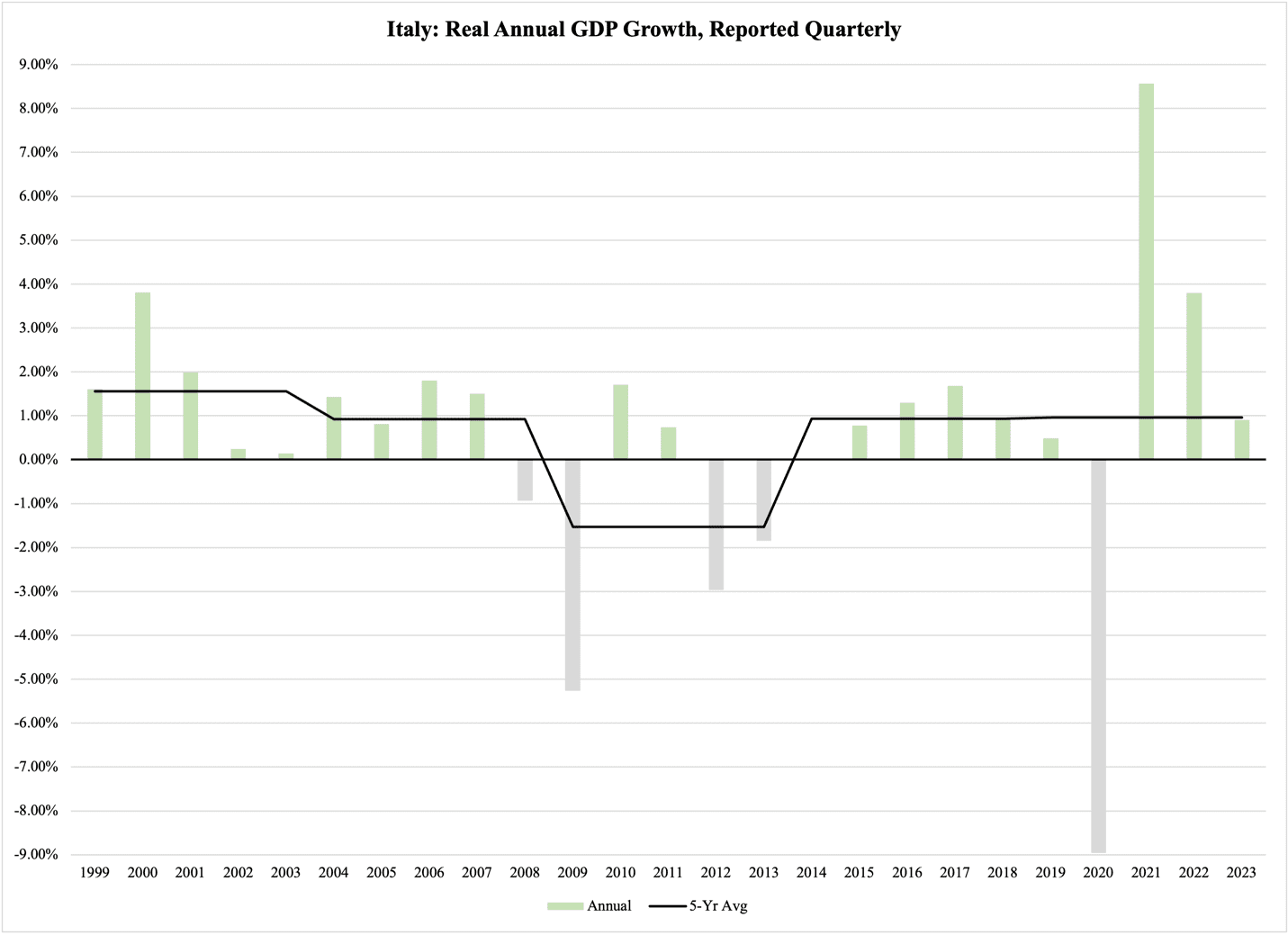

Another reason for the Commission to not go ahead with the excessive deficit procedure is that it comes at a very bad time. Europe as a whole is in the first stage of a recession that will probably be both deep and long, and the Italian economy is no exception. So far, unemployment has remained steady at around 7.6%, with 22.6% among young workers, but in terms of GDP growth, the Italians have little to brag about and a lot to wish for. As Figure 2 shows, the real expansion of the Italian economy stopped at 0.9% in 2023:

Figure 2

To make matters worse, the long-term growth trend is tepid at best. The black function in Figure 2 above reports the average growth rate for five-year periods:

Over the past five years, 2019-2023, the average ticked up to 0.96%.

Low GDP growth is never good, but it is a terrible ingredient in an economy that is being subjected to the EU’s excessive deficit procedure. As Europe learned so painfully during the Great Recession 15 years ago, the enforcement of the Stability and Growth Pact means higher taxes and lower government spending. In combination, these policy measures take more money away from the private sector and give less back, which, bluntly speaking, translates into lower economic growth and higher unemployment.

If Italy were to have a decline in GDP growth, especially at this time, the result would be catastrophic for the country. It has sustained a brittle state of economic stability with an economy expanding at not even 1% per year, on average; the only major cost has been perennial budget deficits. There is no doubt that this deficit must come to an end, but an excessive deficit procedure is not the right way to close the fiscal gap. On the contrary, just like in Greece, it will depress the economy, explode the budget deficit, and, at the very best, achieve a balanced budget after an arduous process that will make Italy a much poorer country than it is today.