In Part I of this article, I showed how economic growth has slowly declined in all major industrialized economies. I did my review based on 20 countries from around the world, including Australia and Japan, but the GDP growth problem is most pervasive in Europe.

The 20-country sample includes 16 from Europe: Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom.

These countries were selected based on the long-term availability of GDP data, which the United Nations produces of increasingly good quality. It is clear that economic growth has fallen in these countries:

Since this period excludes the artificial economic shutdown in 2020, we are looking at numbers that are entirely organic: they represent the actual growth rates in economic activity in these countries. The stunning decline begs us to explain where it comes from.

You would think that economists would flock to this question. If we can understand why our economies are stagnating, we can implement reforms that once again unleash their growth potential. With higher growth, people have better personal finances, they have better jobs and career opportunities, and they get better returns on investing in their skills and education. We as a society have more resources to put toward complex challenges like health care, education, retirement security, and public safety. There will be more money to invest in technological progress, the upkeep of our infrastructure, and the production of energy.

If we choose not to solve the problem of economic stagnation, we can look forward to a life much like that which people endured under the Soviet empire. We can expect each new generation to grow up to a slightly less prosperous life than what we have enjoyed; we can expect increasingly tense political battles over the allocation of increasingly scarce resources between pressing societal needs.

Only a fool who believes that economic growth destroys the environment could possibly wish for our economy to move backward instead of forward. Therefore, since this is an economic problem, it is essential for us economists to solve it.

Sadly, the economics literature has made only scant attempts at doing that. The closest our profession has gotten to a solution is to define something we call “The Great Moderation.” This is a theory about why the major economies in the world went through a phase of historically low GDP growth, but also why that period was comparatively free of sharp swings in economic activity.

Depending on your source, the Great Moderation is said to have covered the 1990s and 2000s, or to have begun already with the 1980s. Both views put an end to the period when the Great Recession breaks out in 2008.

Since there seems to be more agreement on the 1980s as the start of the period, that is the period I will refer to here.

According to the Great Moderation narrative (it is not nearly developed enough to be called a theory), the core feature of the period was a high degree of economic stability and therefore a high degree of economic predictability. It is easy to find references to the Great Moderation in these very terms; one good example is Charles Bean, Deputy Governor for Monetary Policy at the Bank of England, who in his 2010 Joseph Schumpeter Lecture at the annual meeting of the European Economic Association referred to the Great Moderation as “characterised by an unusually high degree of macroeconomic stability, with steady growth and low and stable inflation in most of the advanced economies.” (“The Great Moderation, The Great Panic, and The Great Contraction” Journal of the European Economic Association (April-May 2010).

It was, Bean explains, a “widespread and prolonged experience of stable growth and low inflation” that “resulted in an overly optimistic assessment” of the economic present and future. He gets support for this view from Ben Bernanke, former chairman of the Federal Reserve (“A Century of U.S. Central Banking”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, Fall 2013).

Both these two central bankers are correct insofar as overall macroeconomic stability is concerned, but they fail to mention that in the early 1990s (Denmark suffered a protracted recession in the late 1980s), Europe was rocked by a recession that in some countries had far-reaching repercussions. The British pound came under hard pressure from global currency speculators, which led to a short but serious recession. The Swedish economy fell into a depression-like recession where almost one in five workers was unemployed at one point and GDP contracted three years in a row.

With these exceptions acknowledged, it remains true that the period from the 1980s through the 2000s was, in a sense, a period of macroeconomic stability. The question is why this was so, and why the period ended abruptly in 2008.

Economists have not been able to explain where the Great Moderation came from; we will look at some attempts to do so in a moment. First, though, a few words on what brought the period to an end. In his aforementioned article, Bernanke makes a common-sense but nevertheless relevant point about the role of human psychology:

One cannot look back at the Great Moderation today without asking whether the sustained economic stability of the period somehow promoted the excessive risk-taking that followed. The idea that this long period of relative calm lulled investors, financial firms, and financial regulators into paying insufficient attention to risks that were accumulating must have some truth in it.

This view is shared by Brookings Institution economist Donald Kohn. In a reference to Hyman Minsky, one of the world’s foremost experts on economic stability, Kohn suggests that the fundamental factor that brought the Great Moderation to an end “was complacency mixed with hubris.”

Stanford University economist John Taylor expresses a similar view, though with the finger pointing not at the financial industry but at the Federal Reserve (“Macroeconomic Lessons from the Great Deviation” NBER Macroeconomics Annual, January 2011). Taylor explains that the Federal Reserve contributed to the demise of the Great Moderation by irresponsibly lowering its federal funds rate

below the level implied by monetary principles that had been followed for the previous 20 years. … The deviation was larger than any other during the Great Moderation—on the order of magnitude seen in an unstable decade before the Great Moderation.

For a more detailed insight into Taylor’s economic thinking, see his recent interview with economist Vance Ginn on the Let People Prosper show.

The idea that the Great Moderation lured influential decision-makers into unwise risk taking is shared by the aforementioned British central banker Charles Bean. His analysis, which is technical in nature, explains that “a variety of distorted incentives” and “the opaque structure of some” products on some asset markets conspired with “the high degree of interconnectedness between financial institutions.” Once there was a big enough disturbance in one part of the economy, it spread far wider and more rapidly across the economy than it would have done historically.

If we ignore the fact that Bean, Taylor, and Bernanke do not note that GDP growth was actually declining throughout the Great Moderation, their explanation of the phenomenon itself, including its demise, is perfectly reasonable. They certainly make a lot more sense than contributions based strictly on econometrics, the academically favored flavor of economics. Despite impressive technical prowess, practitioners of econometrics have failed utterly at explaining the Great Moderation.

A pertinent example is offered by European University Institute economist Fabio Canova. In “What Explains the Great Moderation in the U.S.? A Structural Analysis” (Journal of the European Economic Association, June, 2009), he elaborates in great detail on how he can manipulate his econometric model back and forth while reaching absolutely no useful conclusions on why the Great Moderation happened.

In a similar fashion, Wen-Shwo Fang, a Taiwanese economist, and Stephen Miller of the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, spend 20 pages in the Southern Economic Journal’s January 2008 issue, trying to analyze “The Great Moderation and the Relationship between Output Growth and Its Volatility.” They end in an “apparent inconclusiveness,” unable to offer any kind of explanation of the Great Moderation phenomenon.

But all hope is not lost. The three economists Domenico Giannone, Lucrezia Reichlin, and Michele Lenza, are at least able to point in the right direction. In their article “Explaining the Great Moderation: It’s Not the Shocks” (The Journal of the European Economic Association, Apr.-May, 2008), they conclude that the Great Moderation must have its origin in some kind of structural change to the economy.

Although they offer no hypothesis on what the structural change might be, they are correct in that a shift in the institutional structure of the economy took place during the Great Moderation period. That structural change is the growth of government.

I have covered the relationship between economic stagnation and the growth of government in numerous articles; my benchmark reference remains my book Industrial Poverty from ten years ago, where I define the period called the Great Moderation as a period of a slow, agonizing drift into economic stagnation. I also point to the terrible consequences that this drift into an economic quagmire has for public finances—and all the services that government has promised people through the welfare state.

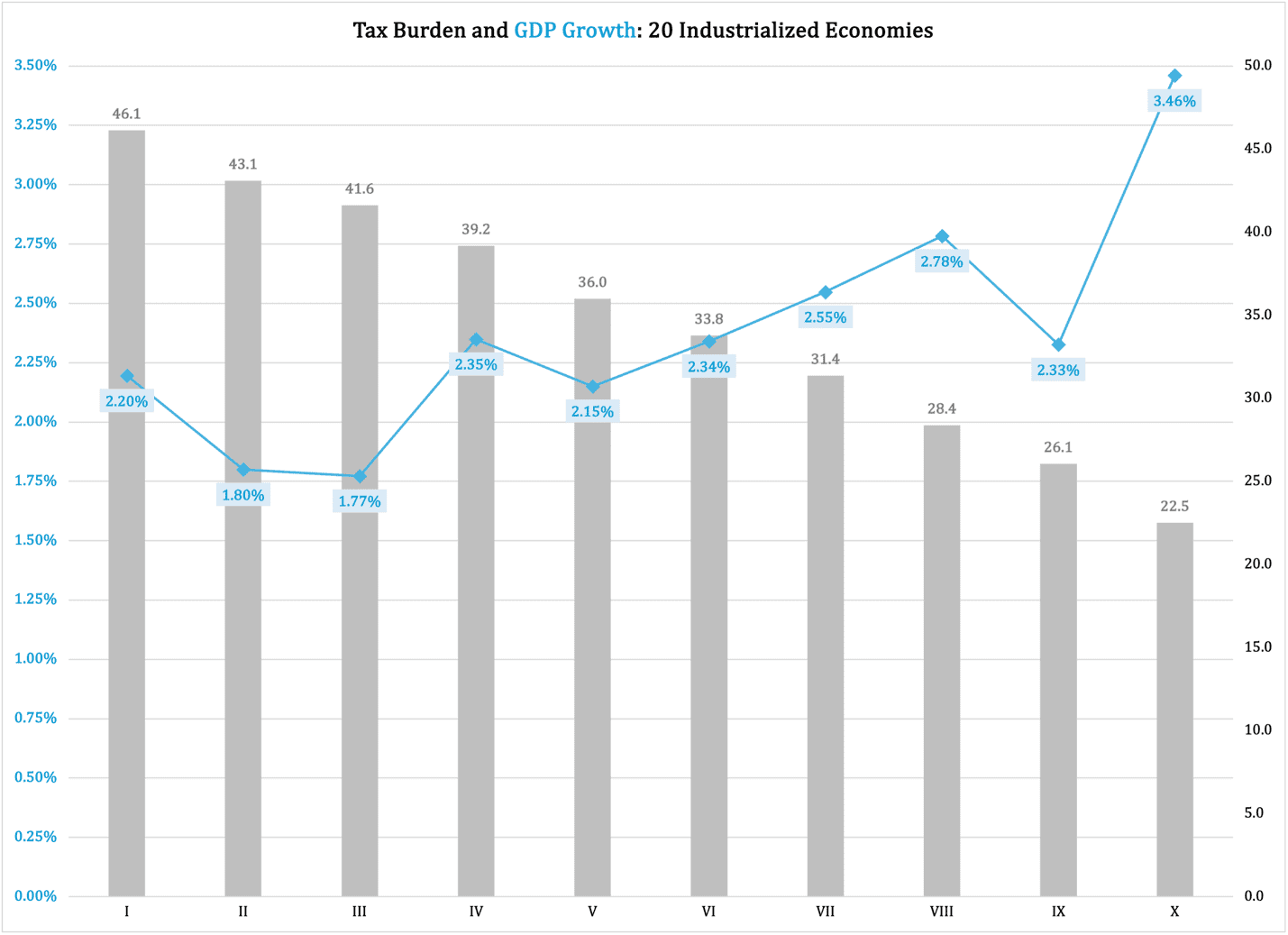

The key point here is that growth in government causes economic stagnation. Generally speaking, there is a tipping point where the government size weighs so heavily on the economy that GDP growth is permanently lowered. To illustrate this point, let us add one variable to the GDP growth numbers from the aforementioned 20 industrialized economies. That variable is the tax burden, specifically the total amount of taxes collected in an economy, divided by the GDP of that economy.

In 1971, only one of these 20 countries had a tax burden above 40% of GDP (Denmark at 41.4%). A total of nine countries had a tax burden below 30%, five of which were below 20%. Half a century later, eight of them exceed 40%, with the top three being Denmark at 47.4%, France at 45.2%, and Austria at 43.3% (narrowly beating Finland and Sweden). By contrast, only four countries maintained a tax burden below 30%, and not a single one was below 20%.

In 50 years, the unweighted tax burden for these 20 economies slowly drifted upward from 29.2% to 37.4%. The bulk of the increase happened in the 1970s and early 1980s, whereafter the negative effects of these tax burdens gradually spread through these economies.

Figure 1 reports the result of a comprehensive comparison of GDP growth and the tax burden in these 20 economies. To avoid the distortionary effects of the 2020 economic shutdown, the cutoff year is 2019. This gives us a total of 1,020 pairs of observations of tax burden and GDP growth, which we then sort into deciles (each with 102 pairs of observations). The result is compelling:

Figure 1

It is nearly impossible for an economy with a 40+% tax burden to achieve even 2% growth; the average growth rate under a tax burden in that range is 1.9%. When the tax burden is 30-40%, the average growth rate is 2.4%, while it closes in on 2.9% when the tax burden falls below 30%.

Let us remember that these are 20 countries, not the full roster of industrialized economies. The selection was based on the availability of high-quality GDP growth data, which again limited the selection. Nevertheless, the numbers in Figure 1 do not lie:

a) There was no Great Moderation—it was the Great Stagnation;

b) If we want to return Europe to high economic growth, the only path forward is to structurally reduce the size of government.