The European economy has ground to a halt. In the fourth quarter of 2023, the gross domestic product for the EU as a whole increased by a meager 0.1% over the fourth quarter of 2022. The euro zone’s GDP did not grow at all: it stood still.

Using Eurostat’s ‘raw’ inflation-adjusted data, we also find that this was the third quarter in a row when both the EU and the euro zone had a growth rate below 1%. Several countries now meet the technical definition of a recession, namely two consecutive quarters with a shrinking, ‘negative growth’ GDP: Austria, Czechia, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Ireland, Luxembourg, Netherlands, and Sweden.

It was not very difficult to predict this recession; while America bounced back quickly from the pandemic-related economic shutdown, it took Europe well into 2022 to recover lost economic activity. Then came the ECB’s necessary but still painful monetary tightening, which forced the euro zone to cope with both rising interest rates and lingering high inflation.

As expected when a central bank tightens the money supply, inflation has come down: in February it stood at 2.8% in the EU while the euro countries averaged 2.6%. However, this has not yet led to a drop in interest rates, something that seems to be stirring impatience among analysts and commentators. Just as there is pressure mounting on the Federal Reserve to cut its federal funds rate, there is growing ‘speculation’ about when the ECB will cut its policy-setting rates. On March 18th, EUBusiness.com reported:

In Europe the ECB could be seen as the first Central Bank to start cutting rates from June. Expectations are for the Euro to move lower in the coming weeks as markets increase expectations for additional interest rate cuts through the rest of 2024.

In other words, the underlying message is that if the ECB does not cut interest rates, the euro will be punished by the currency market. The central bank is unlikely to pay attention to the exchange rate—they are a lot more concerned with how this unfolding recession is going to affect public finances across the euro zone. If they lower their interest rates too quickly, it will be cheaper for governments to grow their deficits than to restrict them.

On the other hand, if the ECB keeps its three key interest rates elevated, it will have a dampening effect on real-sector economic activity. This dampening effect is not so much linked to corporate capital formation—business investments—as it keeps a lid on private consumption. Economists prefer to mention the former as the private sector’s premier interest-dependent variable, but corporations have other ways of funding investments that are more or less independent of market-driven interest rates.

The main influence of interest rates is on consumer spending, where everything from revolving credit card debt to installment-based mortgages and car loans ultimately responds to changes in the central bank’s monetary policy. If we add a dampening effect on government borrowing, the ECB can indeed hold back real-sector activity by not cutting its interest rates.

The apparent problem with this is that the central bank would then be aggravating the economic downturn that is already throwing a wet blanket over Europe. It is very likely that the ECB will choose to cut interest rates—much in line with the expectations expressed in the aforementioned quote from EUBusiness—but it probably will not happen at their April 11th meeting. That will be the point, though, where they signal a cut at the next meeting on May 6th.

While rate cuts will be helpful for the European economy, it is also important to remember that they are in no way the magic wand that can return GDP growth to high, prosperity-generating levels. During the extended period in the 2010s when both the ECB and the Federal Reserve kept their policy-setting rates very low, neither side of the Atlantic Ocean experienced any spectacular levels of economic growth.

In fact, looking at Europe as a whole, it is close to impossible for the continent to reach a sustained average of 3% real GDP growth. A year’s worth of 2% GDP expansion is almost worth a toast in Yamazaki single malt. Central banks can tip the scale of growth about one percentage point in either direction, which makes a big difference in a stagnant economy but does not allow a country to break free of the chains of overall economic stagnation.

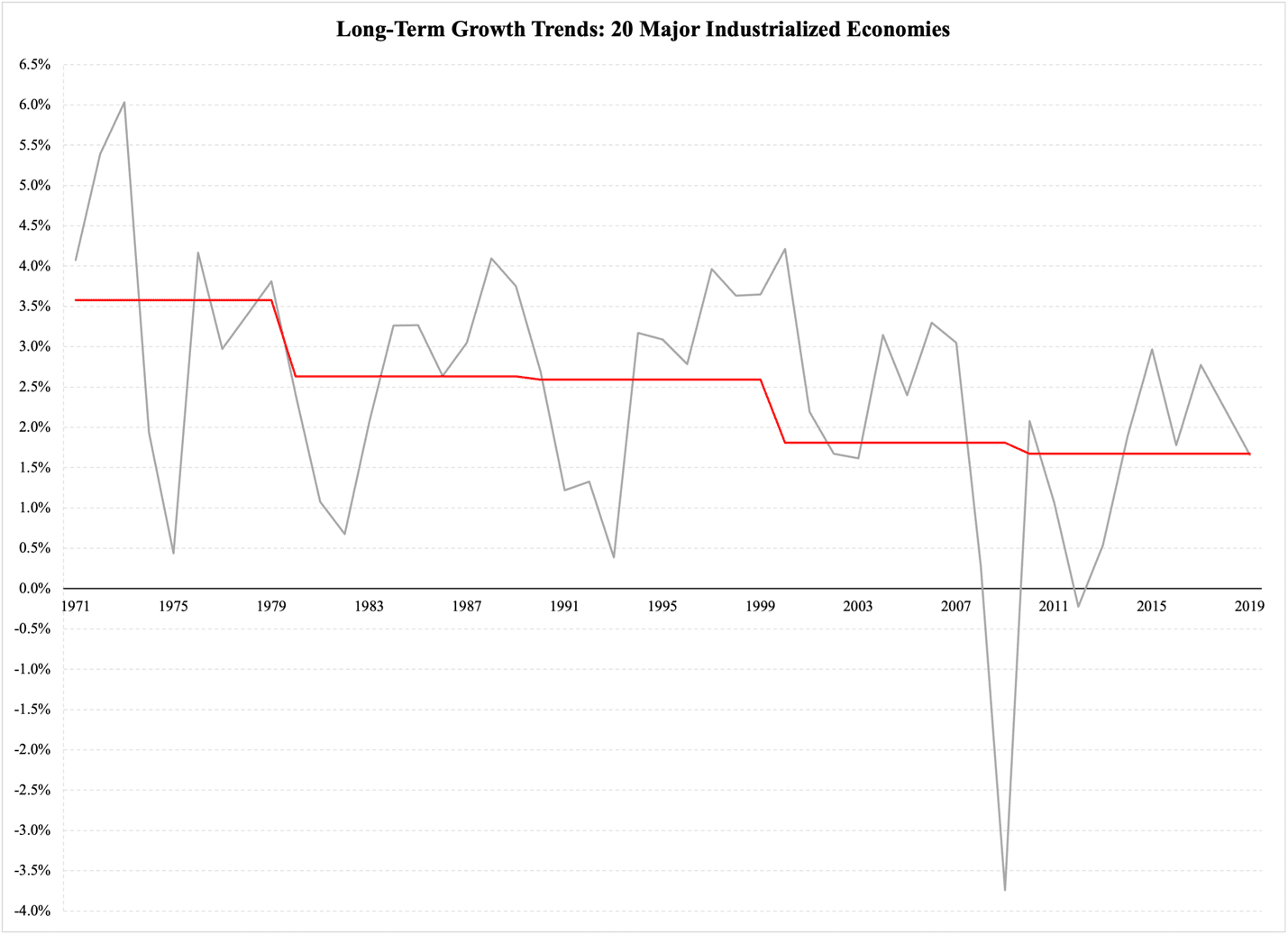

The problem with low economic growth is not new. On the contrary, it is something that industrialized economies generally have experienced since the 1990s, in some cases even longer. Figure 1 reports the unweighted average of real, annual GDP growth rates for 20 representative industrialized economies (see the list of countries below the figure), with black for annual averages and red for decade-long average rates:

Figure 1

There have been many attempts to explain this long-term economic slowdown. One of them, which has almost taken on a life of an urban myth, is that industrialized economies by necessity drift into stagnation because their economies evolve from a manufacturing base to a service base. This Marxist-based argument is easily refutable: if this was the case, the United States—one of the world’s foremost consumers of services—would be at a perennial economic standstill, yet the U.S. consistently outperforms Europe in GDP growth.

Another explanation of the growth downshift in Figure 1 is the so-called Great Moderation hypothesis. It was very popular in economics literature some 10-20 years ago, in part because it offers no substantive reason why GDP growth would slow down at the very point when it did. However, the Great Moderation hypothesis was appreciated among political leaders, as it essentially freed them from responsibility for the economic stagnation that made life more difficult and less prosperous for their citizens.

In Part II of this article, I will examine the Great Moderation hypothesis in detail. I will also present the real reason why modern industrialized economies have not had good growth numbers but have virtually been wading through economic syrup for the past couple of decades.