Europe is already sinking into a recession, with Germany leading the way and Britain following right behind. So far, the U.S. economy has avoided an economic downturn, but that might be changing. According to Federal Reserve Governor Christopher Waller,

growth in real GDP appears to have slowed appreciably in the fourth quarter. The average private-sector forecasts summarized by the Blue Chip survey estimates that real GDP grew 1.5 percent in the final three months of 2023. The Atlanta Fed’s GDP Now model, based on data in hand, currently stands at 2.2 percent.

Governor Waller also points out that “a modest acceleration in job creation” in December should be viewed in the context of downward revisions of job numbers that the Bureau of Labor Statistics did throughout 2023. I made the same point recently. Waller also noted that “data on job openings indicates ongoing moderation” in demand for labor.

In effect, Waller is predicting a recession. Many forecasters did so in 2023 (not Waller, though, as far as I have been able to determine) while I consistently disagreed with them. I just did not see a recession in the economic data. However, things may have changed in the fourth quarter of last year; we will not have official GDP numbers from the Bureau of Economic Analysis until January 25th, but if Governor Waller is correct, there is definitely at least an economic moderation coming.

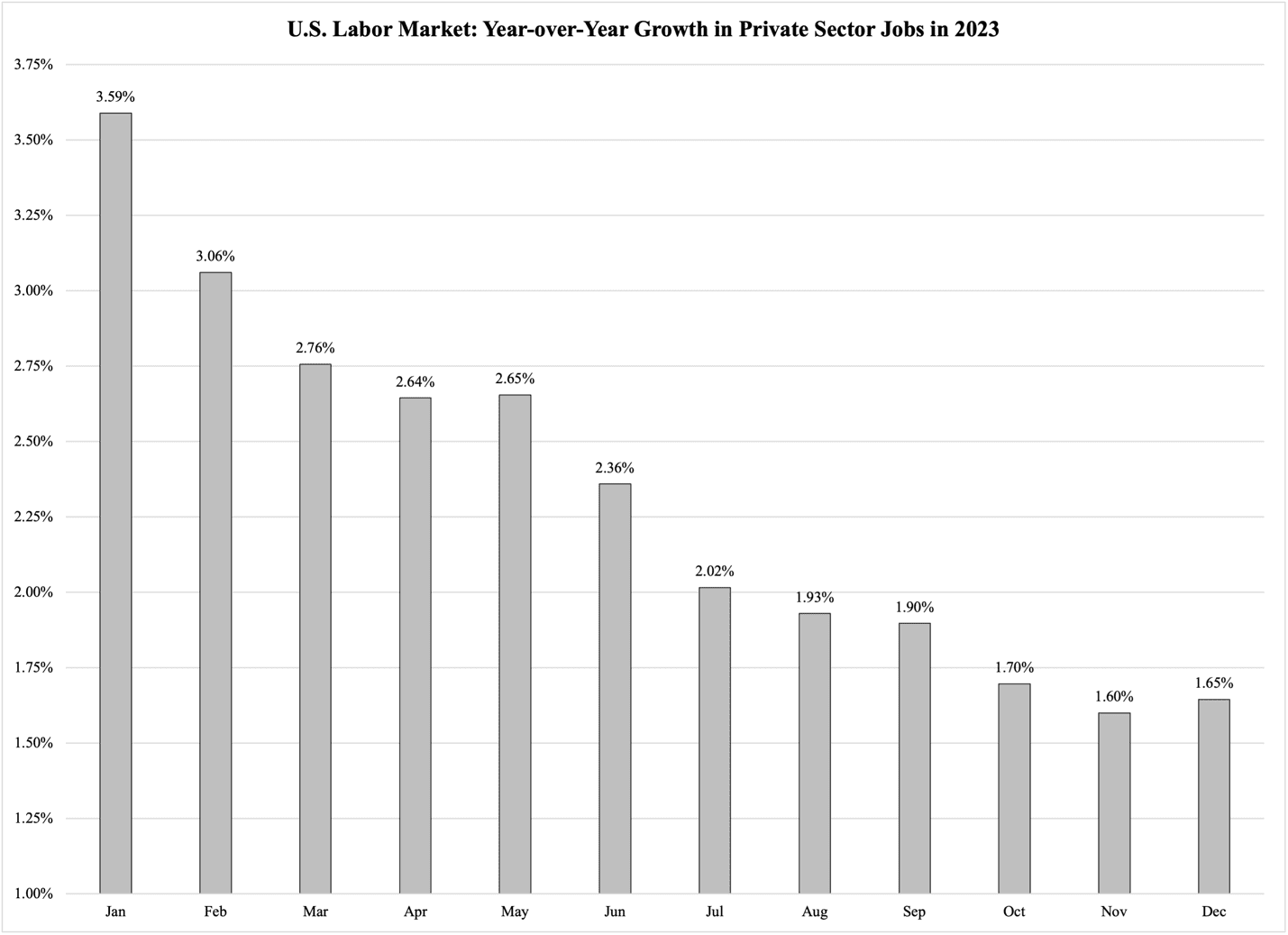

He did not go into much detail regarding the labor market, so let’s add some numbers there. In December, there were 134.9 million people working in the private sector of the U.S. economy. This is 2,184,000 more than in December 2022, or a 1.65% increase. This growth rate for private-sector jobs is a touch lower than the December numbers in the pre-pandemic economy. From 2014 through 2018, the private sector increased its payroll by anywhere between 1.7% to 2.5% on an annual basis.

The difference between these numbers and the number for December 2023 is not dramatic, and in itself does not add to the picture of a looming recession. However, a review of the recent trend in the private sector’s jobs growth paints a different picture:

Figure 1

The slowdown in jobs growth is not part of a ‘return to normal’ in the recovery after the pandemic: we are now more than two years out of the recovery. Looking more generally at how fast the private sector normally adds jobs, the last three months of 2023 look modest at best:

As far as workforce participation is concerned, numbers are still relatively good, with 62.2% of the workforce-age population (16 years old or more) either working or looking for work. Only 3.5% of the workforce was unemployed in December. This is up from 3.3% in December of 2o22, but lower than the same month in the reasonably good years 2014-2018; in 2019, the strongest year of the Trump economy, unemployment crept down to 3.4%.

At the same time, while unemployment is not at any dramatic level, nor showing any signs of rapidly rising, the slowdown of job creation is usually a first sign that the economy has reached the peak of its business cycle. In the context of Governor Waller’s statements, the private-sector jobs numbers point in the direction of a wider economic slowdown. However, as mentioned we need more solid data to make a definitive call.

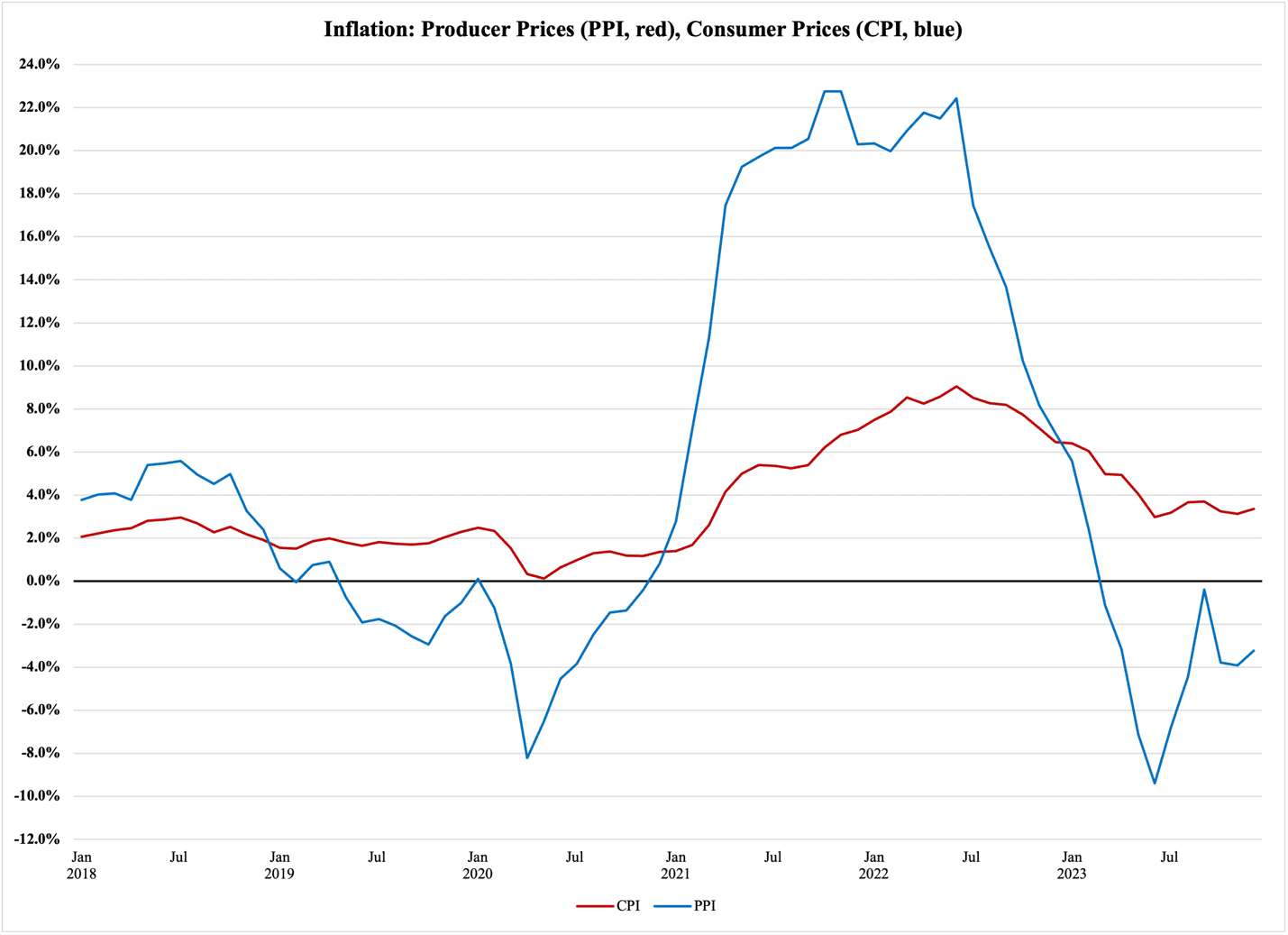

In addition to the preliminary GDP numbers for the fourth quarter, which will be released on Thursday the 25th, the inflation numbers for January will tell us a great deal about where the economy is headed. In addition, we should keep an eye on the consumer price index (CPI) inflation rate. If its January figure comes in below 3%—it stood at 3.35% in December—and if producer prices continue to fall, we have good reasons to predict a recession.

As explained in Figure 2, which reports producer and consumer inflation since 2018, producer prices have been falling since March 2023:

Figure 2

With producer-price inflation in the negative, i.e., deflation, there is an underlying pull on consumer price inflation to fall further. It has been kept up above 3% by the overall strength of the U.S. economy; if, again, Federal Reserve’s Chris Waller is correct in his assessment that the economy cooled in the fourth quarter, the push upward on consumer prices from a strong economy will be gone from the statistics by January.

Technically, the fact that consumer inflation (the red function in Figure 2) remained elevated through December could be interpreted as a sign that fourth-quarter economic activity was stronger than Governor Waller suggests. However, inflation does not respond immediately to changes in economic activity: just as it was slow to take off after the monetarily driven fiscal expansion in 2020 and 2021, it is reluctant to come down when the monetary pressure is gone and all we are left with is demand-driven price hikes.

To conclude, if the GDP numbers for the fourth quarter come in at about the levels Governor Waller predicts, namely closer to 2% year-to-year growth, and if CPI inflation for January is below 3%, then we can raise the recession flag for the U.S. economy.