The European Commission has released the spring 2024 edition of its European Economic Forecast. It is an ambitious attempt at presenting the EU economy in the best light possible.

I give them high marks for effort. As for the economic outlook itself, I would recommend any reader of their report to take it with a grain of salt—or two.

To begin with, economic forecasting is one of the most thankless projects an economist can get into. Almost all forecasts are inaccurate in one way or another; no matter how much statistical information you process, accuracy is almost impossible. If you predict inflation to be 3.2% and it turned out to be 3.0%, people can point to your forecast and say you were wrong.

Economists often have themselves to blame for their notoriously inaccurate forecasts. They boast about using computer models with thousands of variables and all the bells and whistles that modern econometrics has to offer. With such impressive resources at his disposal, the economist should be able to predict every key variable in the economy with pinpoint accuracy—should he not?

No. He may want to do that, but he can’t. As I explained in my doctoral dissertation a quarter of a century ago, precise economic forecasting is logically impossible. British economist John Maynard Keynes summarized the feeble nature of precise forecasting by pointing to its flip side: “It is better to be approximately right than exactly wrong.”

In other words, an economist is more credible if he predicts that inflation will be in the realm of a small statistical window, e.g., 3.3-3.5%, than if he gives his forecast an exact number, such as 3.36%.

In addition to the caveats that come with forecasting itself, let us not forget that the European Commission has a deeply rooted desire to paint the European economy positively. I understand why the European Commission’s spring 2024 economic forecast tries to strike a note of optimism. To begin with, nobody wants an economy to be in a recession—but there is also an election in June; the better the EU looks going into the election, the less the chance that people will support EU-skeptic parties, right?

With this in mind, I scratched my head at the following conclusion:

The EU economy staged a comeback at the start of the year, following a prolonged period of stagnation. Though the growth rate of 0.3% estimated for the first quarter of 2024 is still below estimated potential, it exceeded expectations.

They also suggest that the uptick in GDP growth marked “the end of the mild recession” that apparently came and went in the second half of 2023.

This is the essence of the optimism with which the European Commission—in Table 1 on page 1 of their report—predicts 1.0% real GDP growth in the EU this year and 1.6% in 2025.

This is a nice example of a forecast based on the notorious ambition to be accurate, but it is also a display of political bias. The Commission simply wants to produce numbers that are just a hair on the right side of certain key thresholds. The best example is their forecast of budget balances in the several EU states—the last column in Table 1 of their report—where the Commission conveniently predicts that at least six EU states will run budget deficits just a hair below 3% of GDP.

This is the deficit ratio that is stipulated in the EU’s Stability and Growth Pact (or whatever its new name is going to be). For years, the EU failed to enforce the Pact, which effectively meant that nobody respected it anymore. In recent months, the Commission and the European Parliament have been trying to reform the Pact and give it back its erstwhile clout. Therefore, the Commission needs to start acting tough on member states who break this rule.

At the same time, the EU cannot have a long list of countries that are in breach of the deficit rule in the Pact—especially not going into an election. There cannot be any suspicion that the European Commission will start the next parliamentary term with a massive crackdown on fiscally irresponsible member states.

For this reason, in order to not once again look feeble because they fail to enforce their own laws, the European Commission appears to have done some creative work with its forecast through 2025. The result is that excessive budget deficits in many cases end up just a hair short of the 3% threshold.

For Latvia, the Commission predicts that GDP will expand by 1.7% this year, up from a decline of 0.3% in 2023. In 2025, the Latvian economy is expected to grow by 2.6%. At the same time, their government is going to run bigger budget deficits: from -2.2% of GDP in 2023, it expands to -2.8% in 2024 and -2.9% in 2025.

This budget deficit trend is abnormal for such a strong improvement in GDP growth. But if we accept that stronger growth comes with larger deficits, it is more than a little unreasonable that the deficit would cap at 2.9% of GDP; the implied trend points to 3.2-3.4%.

The forecast for Austria comes with similarly weird numerical somersaults. An economy that turns around, from -0.8% growth in 2023 to 0.3% and 1.6% in this year and next, is at the same time supposed to generate a budget balance of -2.7%, -3.1%, and -2.9%. However, for a welfare state like Austria, 1.6% growth is nowhere near adequate to make a dent in the budget deficit. The -2.9% deficit figure for 2025 seems more like fiscal wishful thinking than a real forecast.

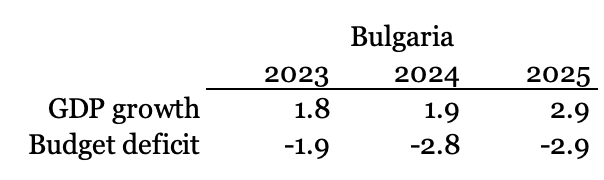

Perhaps the most humorous example is found in Bulgaria:

Table A

To be perfectly honest, these numbers are so convenient that I cannot help but wonder if they are the product of a ‘festive forecast,’ the Swedish name for a—whether deliberate or not—overly optimistic one. I can definitely see the budget deficit shooting up toward 3% of GDP this year, but there are no circumstances under which I can imagine the Bulgarian economy growing at 2.9% in 2025. I am sorry to say this to our Bulgarian readers; maybe there will be signs of it later in the year, but not now.

More than anything, the forecast in Table 1 of the European Commission report suggests that the Bulgarian growth number is needed, not predicted. Without it, there would be no reason for the Commission to predict a budget deficit just a hair shy of the 3% Stability and Growth Pact threshold.

Time will tell to what extent the Commission was right in its Spring 2024 economic forecast. I suspect that looking back at it toward the end of 2024, I will have several reasons to repeat my assessment that this report is more wishful thinking than anything else.