In Part I of this article, with reference to the European Parliament’s plans to expand the taxation powers of the EU, I explained:

It is always easier to expand taxation powers if government also gives good reasons for how that money will be spent. … government can create attractive spending programs; if they benefit a large enough segment of the population, public support is almost a given—regardless of how strongly we believe in the limitation of government powers.

The programs on which the EU would like to spend its newfound revenue are not kept secret. In a report presented to the European Parliament on October 31st last year, the parliamentary Committee on Regional Development proposed a repurposing of the EU’s structural fund spending. Broadly speaking, the money is supposed to be used to benefit regions that are negatively affected by “industrial, automotive, ecological, digital, and demographic transitions.”

In plain English, the structural funds are supposed to mop up the scraps where the European Union has caused economic destruction with its mad intent to ‘decarbonize’ the economy. The report even admits as much, advocating for the adaptation of spending

to support sectors undergoing complete transformation as a result of policy decisions, such as the transition towards the decarbonisation of road transport by 2035

With a focus on the automotive industry, the report recognizes that “financial support is crucial to facilitate investments in research, development, and innovation, as well as the necessary upgrades to physical assets and infrastructure.” However, the authors of the report also acknowledge the fact that the economic destruction of the ‘green transition’ goes well beyond what this kind of support can provide:

European support can play a pivotal role in ensuring a socially acceptable and inclusive transition for workers and companies affected by the changes in the automotive sector. By supporting workforce re-skilling programs and providing alternative employment opportunities, funding support can help mitigate the social impacts of the transition.

So far, the report—which was adopted by the Parliament on December 12th—sounds pretty much like a mouthpiece for traditional European industrial interventionism. Government causes a problem (‘decarbonization’) and wants more money to find a solution to that problem. However, that changes on a dime once we get to the fine print of the report and the resolution adopted by the parliament. Taking a more general aim at the role of government spending, the Report explains (item Q):

EU policies must not be territorially blind in order to avoid aggravating the phenomenon of ‘the geography of discontent’ and to generate acceptance among industry, local authorities and the people affected of the main common goals on the decarbonisation of the economy

And what exactly does the Report mean it has to do “to generate acceptance” for its economic destruction? Enjoy this odyssey into the Orwellian domains of the English language:

effective strategies to enhance the attractiveness of post-industrial regions include improving quality of life, investing in education, healthcare, infrastructure, and local entrepreneurship, facilitating access to affordable housing and creating incentives for young professionals and families to remain in or move to these areas

All of a sudden, the EU has elevated its spending ambitions beyond simply reimbursing individual industries for the destructive, even catastrophic costs that the EU has imposed on them. The goal is now to get the EU involved in spending in such central government functions as education and health care.

It is crucial for all EU citizens to understand what this means. The report mentions these ambitions in passing, which by the informal protocol of political communications means that this is a main point in the report. Even though it sounds as if the European Union can get involved in health care spending in selected regions of a country, in reality, that is not the case.

The reason is simple: health care funding is provided through a national system, which does not discriminate between individual regions. The European Union simply cannot come in and drop money for preferential reasons in one region without distorting the national funding model that the government of that country has put in place.

To see why, let us examine the funding models for health care across the EU. The numbers below are from 2019; the newest data from Eurostat is from 2021, a year that was partly distorted by temporary pandemic-related spending. The 2019 numbers give a structurally better picture of the permanent funding models at work across Europe.

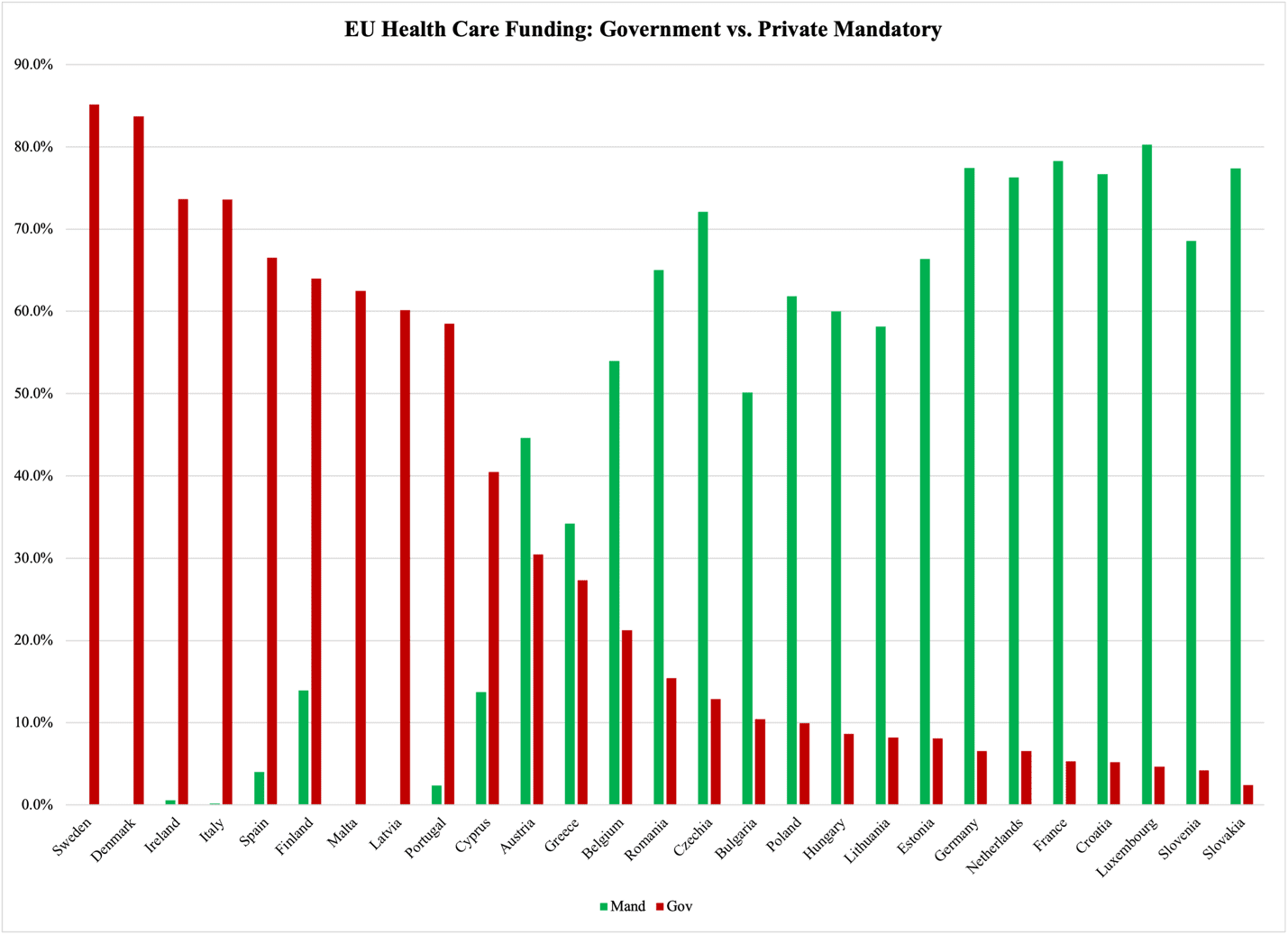

Essentially, there are two different models for health care funding: one that relies primarily on government money and one that relies on private, mandatory funding. The former is often referred to as a ‘single payer’ model; the latter involves varying levels of choice between government-regulated but technically private insurance providers. Figure 1 illustrates how the 27 EU member states fall into either category, with the vertical axis reporting how big a share of total health care spending either government (red columns) or mandatory providers (green) account for. Sweden and Denmark represent the ‘government’ extreme, with more than 80% of their health care systems being funded by government:

Figure 1

Nine countries use the government model, with taxpayers directly paying for more than 50% of health care. The other model, with mandatory plans funding at least 50% of health care, is at work in 15 countries, with three countries, Cyprus, Austria, and Greece, relying on a mix of funding sources.

The choice of either model is not random, nor ideologically neutral. With private plans operating under a government coverage mandate, there is an element of choice and therefore competition involved. This means that some market mechanisms are involved in keeping costs down and quality up. And it works: as I explained in my 2021 ebook Tax Cuts Don’t Work (pp. 58-62), the Dutch reform in 2006, which shifted the model from ‘red’ to ‘green’ in terms of Figure 1, reduced the cost of health care while increasing quality and improving access to care.

If the European Union is going to involve itself in health care funding at the individual member state level, or even more decentralized than that, it could easily upset a well-working national model for health care funding.

To be blunt: if the involvement comes in the form of direct government funding, what will this do to the model used in 15 countries where government funds play a minor role in health-care funding?