On March 26th, INSEE, the French national institute for statistics and economic studies, released a report on the state of public finances in the country. Their headline number was the consolidated fiscal deficit, which reached 5.5% of GDP for 2023, up from 4.8% in 2022.

The number caused quite a stir in French politics, with a vigorous public debate and various media voices making more or less colorful contributions. In a bombastic salvo, BVoltaire.fr explained that the report “fell like a tree on the Macron House” and that President Macron and Economy Minister Bruno Le Maire, the “two chief lesson givers in power,” are responsible for the biggest fiscal “disaster … since the beginning of the Fifth Republic.”

Meanwhile, Les Echos opined that the government for weeks “had been dreading” the release of these numbers. They also called the increase in the deficit “unprecedented” and accused Bruno Le Maire of being taken by surprise by the numbers.

Le Maire, on the other hand, lamented that “public expenditure has a thousand fathers” but nobody wants to take responsibility for the economy as a whole. He did so in response to the predictable calls from assorted communists and others on the outer leftist rim, to raise taxes on the rich.

According to Les Echos, three-time presidential candidate Marine Le Pen of the Rassemblement National called the numbers from INSEE “appalling” and lambasted “the incompetence of this government.”

Taken together, the French political elite demonstrated impressive rhetorical prowess. As we will see in a moment, the only problem with this performance is that it was entirely misguided.

First, one more word from Economy Minister Le Maire, who insists that he will bring the deficit down to 3% of GDP by 2027. So far, the good minister has not given any hints of how he would achieve this goal, but since his critics in politics and media prefer verbal acuity to factual veracity, perhaps his goal is not so outlandish after all.

The irony buried underneath the public fiscal cacophony in the French media is not very hard to find. The plain truth is that the increase in the national debt is not at all Macron’s and Le Maire’s fault. It is primarily caused by local governments. Explains INSEE:

The public debt of local government increased by €7.4 billion, after -€1.0 billion in Q3. This increase borne by municipalities and departments was due to a rise in loans (+€7.0 billion) and outstanding long-term securities (+€0.4 billion).

Meanwhile, as INSEE notes, the debt owed by the national government, including its social trust funds, actually decreased.

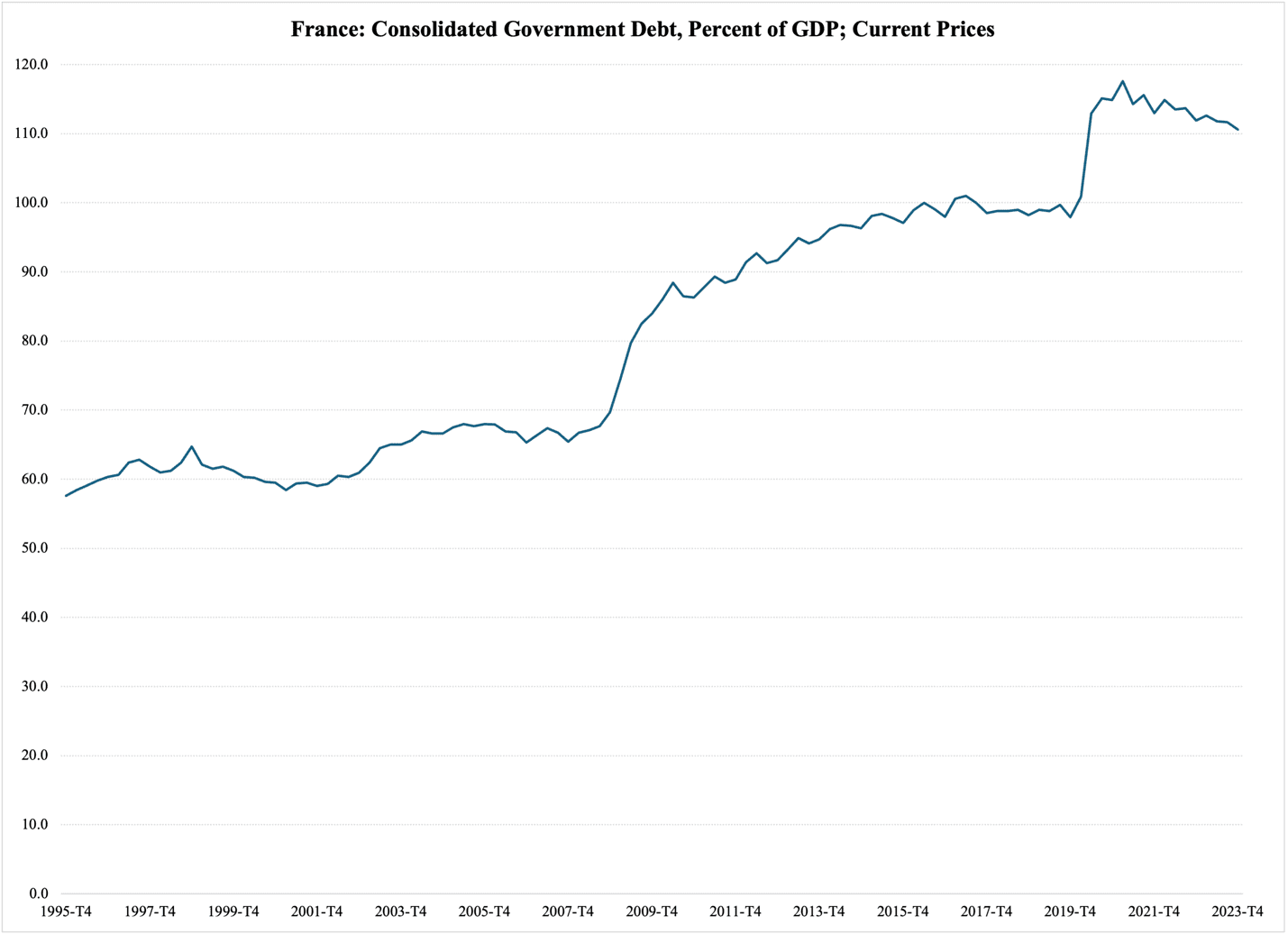

The fiscal rhetoric directed at the government becomes even more perplexing given the recent history of French government debt. Figure 1, which reports the consolidated public sector’s total indebtedness, shows a slight decline in the debt level since the economy started recovering from the 2020 pandemic shutdown:

Figure 1

It is a bit surprising that the French politicians and media did not pick up on this in the INSEE report they are all quick to refer to. With that said, France has a long history of slowly growing indebtedness; before the artificial economic shutdown in 2020, the one big debt leap happened during the Great Recession 15 years ago.

That episode is important for today’s fiscal conversation in Paris. As I explained in Industrial Poverty, pp. 127-131, back in 2009-2014, the French government tried hard to use fiscal austerity as a means to combat its growing debt. Predictably, the austerity measures did indeed slow down the growth of the debt, but they also permanently slowed down the French economy. According to Eurostat,

To be clear, these are unimpressive growth numbers generally, but they are urgently problematic for a country that has such a big welfare state as France does. In 2023, taxes consumed approximately 52% of GDP while total government spending equaled approximately 57% of GDP. About two-thirds of government outlays go to entitlement benefits of various kinds.

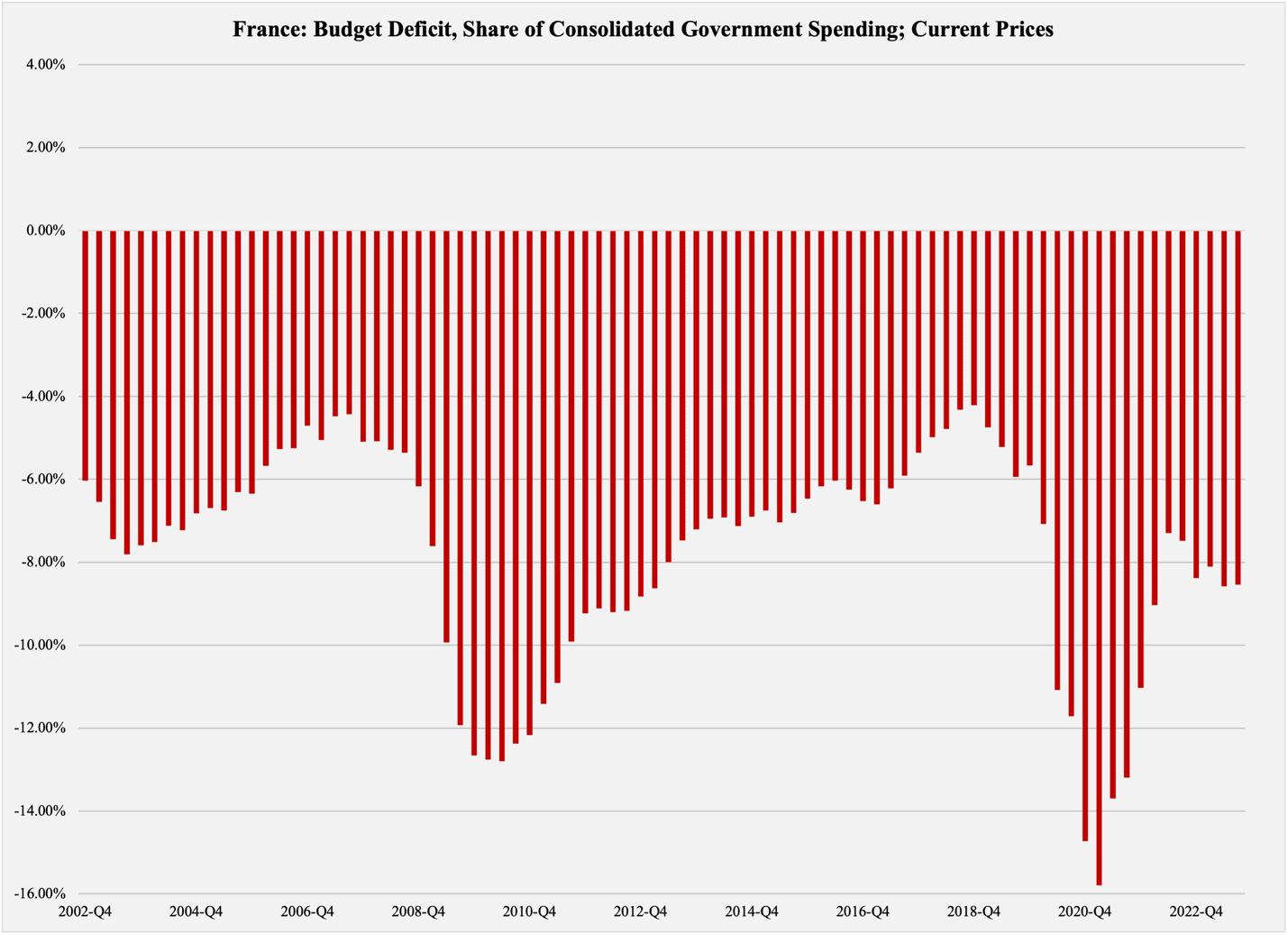

With lower GDP growth comes lower growth in tax revenue. This is an important reason why the French government debt has kept on growing, as shown in Figure 2 below. Its numbers are slightly different from those that INSEE reports and the French public discourse is regurgitating. Rather than dividing the budget deficit by GDP, it is here reported as a share of total government spending. This gives us a more accurate view of the actual shortfall in the budget—a shortfall that has been uninterrupted since at least the fourth quarter of 20o2:

Figure 2

France has a much bigger economic problem than its budget deficit. If Economy Minister Le Maire is going to achieve his goal and reduce the deficit to 3% of GDP by 2027, in terms of the numbers from Figure 2, this means that he will have to reduce it from 8.6% of government spending today, to 5.3% three years from now.

With GDP growth around 1.3% per year over the longer term, there is no hope for tax revenue growth to reduce the budget gap. The calls from the political left to raise taxes on “the rich” (whoever they are) are calls for yet more economic stagnation, and therefore even larger deficits than today.

Without a fundamental revamping of the role of government in the French economy, the only path to a balanced budget that currently is open to the French government is another round of austerity-driven spending cuts.

This, on the other hand, is easier said than done. To balance the budget by spending cuts alone, Economy Minister Le Maire would have to ask the French people to accept well over €50 billion in cuts to total economic outlays. This would include €1.4 billion in reduced defense spending, right when President Macron has expressed a desire to deepen France’s support for Ukraine.

For French households, the €50 billion in spending cuts would mean €34 billion in cuts to welfare state benefits such as health care, income security, and education.

It remains to be seen how such cuts are received by the French political elite. Will government spending, per Bruno Le Maire’s words, still have a thousand fathers—or will the fathers orphan the budget when they realize that it is time to take ownership of the fiscal children they have brought into this world?