According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, in May, 23.6 million people worked for government in one form or another. Since the government workforce climbed above 23 million in October last year, it has remained steadily north of that threshold.

This ‘highest in history’ figure has attracted some attention in the media. Back in January, Terence Jeffrey with the Daily Caller noted this, and other news outlets followed.

Government employment has indeed increased quite a bit recently. In 2023—and so far in 2024—the government workforce has expanded at an average of 2.72% per year. For comparison,

Not even the 1970s can beat the growth in the government workforce that we see today. From 1970 through 1979, the growth rate was 2.69%—some 0.03 percentage points behind the 2023-2024 expansion.

These numbers come in the context of a year-to-year increase in total government spending in 2023 of 5.2%; in the first quarter of this year, that spending increase was 4.6%.

Last year, the federal government, the states, and local governments managed to spend an astounding $10.1 trillion. If the first-quarter figures for 2024 are any indication, we will see government outlays exceed $10.6 trillion in this year.

With this expansion of government, one would expect that government outsizes the private sector and encroaches on its ability to recruit and retain workers. If that were to happen, it would be a fiscal disaster for government, with a shrinking tax-paying private sector and a growing tax-dependent sector.

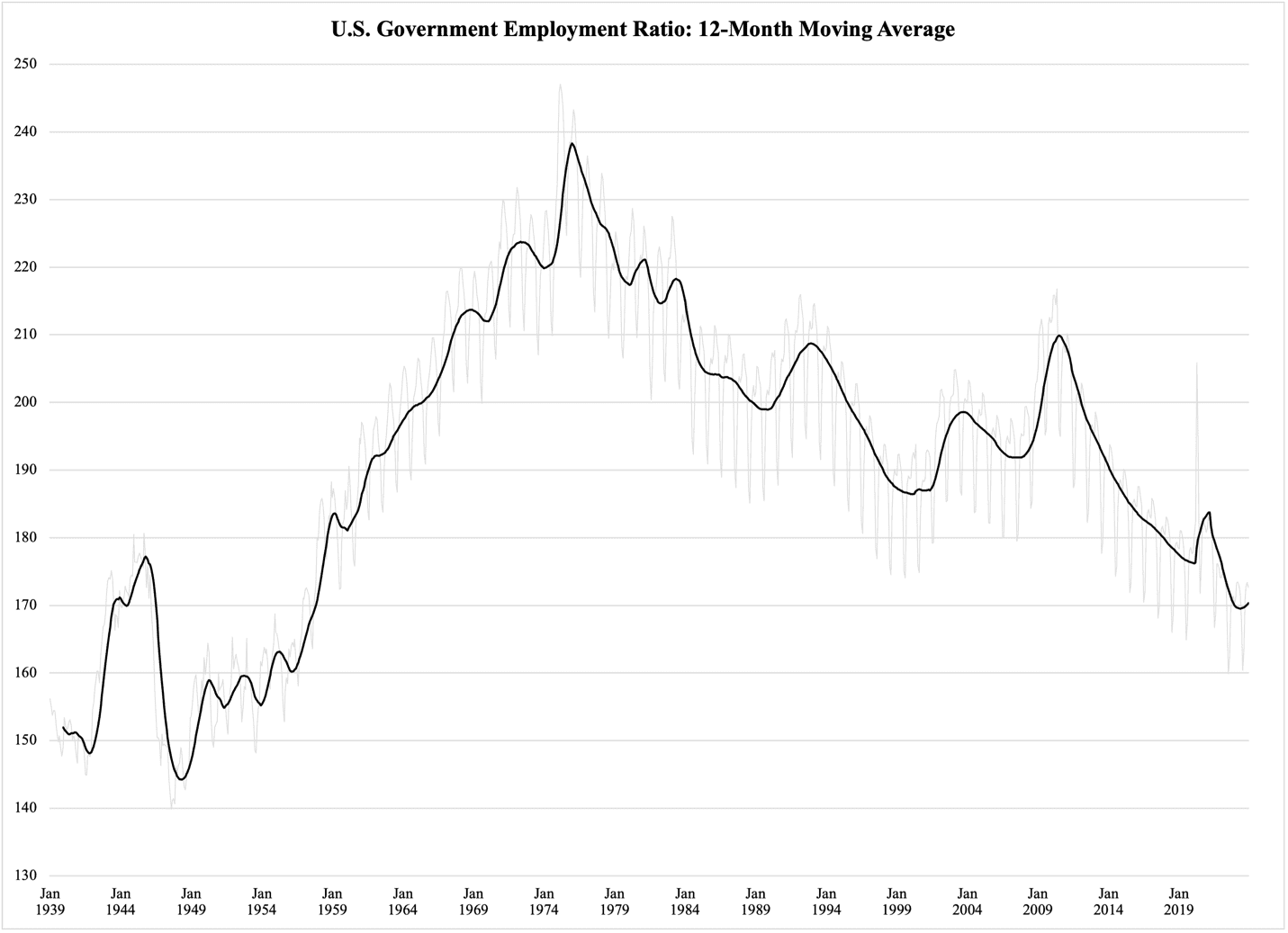

To see if this is where America is heading, we take a look at the government employment ratio, GER, which measures the number of government employees per 1,000 workers in the private sector. Figure 1a has the story:

Figure 1a

As Figure 1a reports, the GER for the U.S. economy has actually been in decline over the past 40+ years. After topping out around 240 in early 1979, the ratio declined in three ‘steps’ which roughly correlate with four presidential terms:

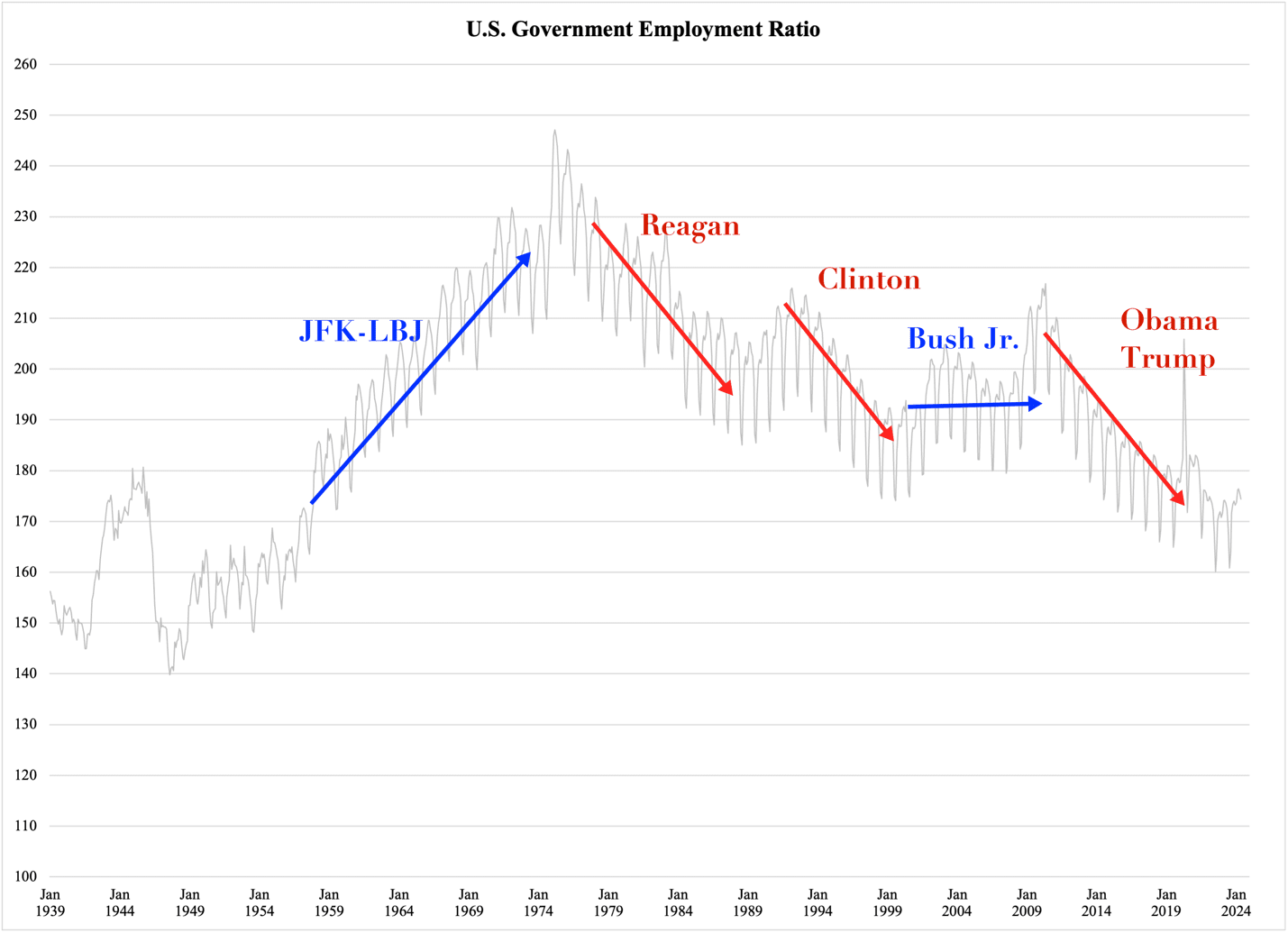

Figure 1b

The GER shows the relative increase in government employment; although government has practically always expanded its payrolls, the GER identifies the episodes when this expansion has outpaced the private sector, and when the private, tax-paying sector’s workforce has grown faster than government.

Starting with the 1960s, the presidencies of John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson—spanning 1961 to 1969—were characterized by a rapid transformation and expansion of the American welfare state. In line with the creation of numerous new programs for government spending and with the expansion of existing ones, both federal and state governments needed to hire a lot of new employees.

The expansion of the new American welfare state continued into the early 1970s and Richard Nixon’s tenure in the White House. Over a little more than a decade, therefore, the government employment ratio rose from 175 to almost 225.

Taxpayers noted the increased cost of government during this period of time. High and complicated taxes stifled the growth of the private sector, contributing to further upticks in the GER. Ronald Reagan won the 1980 election and delved into reforms that would allow the private sector to grow. With his signature, Laffer-inspired tax reforms, he put enough money back into the private sector that its workforce outpaced government for the duration of his two-term presidency.

If Reagan brought the GER down below 200 again by cutting taxes, Democrat Bill Clinton made it fall further by exercising fiscal restraint at the federal level. This rubbed off on the states and helped hold back government expansion in general. Meanwhile, the 1990s saw five years with 4+% real GDP growth:

With the private sector adding jobs at a pace of 2.6% per year in 1997-2000, it handily outpaced the government sector, where the payroll rosters grew at 1.6% per year during the same period of time.

After Bill Clinton came George Bush Jr., whose political focus really did not include the economy. He implemented a two-step tax reform which had some positive effects on the economy, but not to the same degree as the Reagan tax cuts. Furthermore, unlike Clinton, Bush was not too interested in putting restraints on government spending. While Clinton presided over a total government spending increase of 3.9% per year, the Bush Jr. years was a virtual public spending feast, with annual growth averaging 6.4%.

In terms of the public-private workforce balance, Bush Jr. left no real impression. His successor, radically leftist Barack Obama, actually did better in that regard: thanks in no small part to his unwillingness to work on budget deals with a Republican-led Congress, government spending only grew moderately. Unsurprisingly, the government employment ratio fell again.

It continued doing so under Trump’s one-term presidency; when he left office, the balance between government and the taxpaying private sector brought it down slightly below where it was when Kennedy took office in 1961.

Does this mean that the era of big government in America is over? The numbers would suggest as much, but that would be a wildly overstated conclusion. All it means is that we can thank four presidents for—intentionally or not—contributing toward the restoration of a prudent employment balance between government and the private sector.