In its January 30th meeting, the Monetary Council of the Hungarian National Bank, MNB, decided to cut the bank’s three leading interest rates by 0.75 percentage points. The MNB’s base rate went down from 10.75% to 10%, with the deposit rate and the collateralized lending rate at, respectively, one percentage point below and above the base rate.

The Monetary Council motivates the rate cut with both global and domestic economic assessments. Here is how they see the global scene:

The US and Chinese economies grew strongly in 2023 Q4, while European economic growth stagnated. … Inflation in the euro area rose temporarily; however, underlying developments still point to a decline. In the US, the pace of price increases was slightly stronger than expected in December.

However, they explain, the overall global trend of weaker “economic demand and lower commodity prices” points to “a continued decline in inflation rates.”

As for the Hungarian economy, the Monetary Council points to “subdued” economic growth in the fourth quarter of last year:

In November, industrial and construction output and the volume of retail sales fell in annual terms. Primarily due to high inflation, the economy declined moderately throughout 2023, with the outstanding performance of agriculture dampening the decline. The household confidence indicator continued to improve slowly in December.

They also note that “the labor market remains tight” with unemployment at a comparatively low level.

Looking at 2024, the Monetary Council sees further moderation of inflation, which should lead to rising real wages and further strengthening of consumer confidence. They also predict growth in Hungarian exports despite acknowledging that the European economy in general will be weak this year.

It was a bold move by the MNB to lower the interest rate—I recently criticized the ECB for ruling out the option of raising interest rates in the near future. However, my criticism of the ECB was based on the economic conditions of the euro zone. As the MNB’s Monetary Council points out, those conditions are not the best from a business cycle viewpoint. In addition, there is an elevated risk that euro-zone governments will try to coerce the central bank into printing money to fund their growing budget deficits.

Hungary is in a very different situation. While the euro zone is already sinking into a recession, the Hungarian economy remains in good shape. To follow up on the Monetary Council’s point about the labor market: Hungary is one of only ten EU member states that has a workforce participation rate above 80%. Not only that—the rate has been climbing recently:

In other words, in seven years, the Hungarian workforce participation rate rose by a remarkable 6.5 percentage points. Meanwhile, unemployment fell from 5% in 2016 to 3.3% in 2019. After bouncing up to just above 4% in 2020 and 2021, it fell to 3.6% again in 2022.

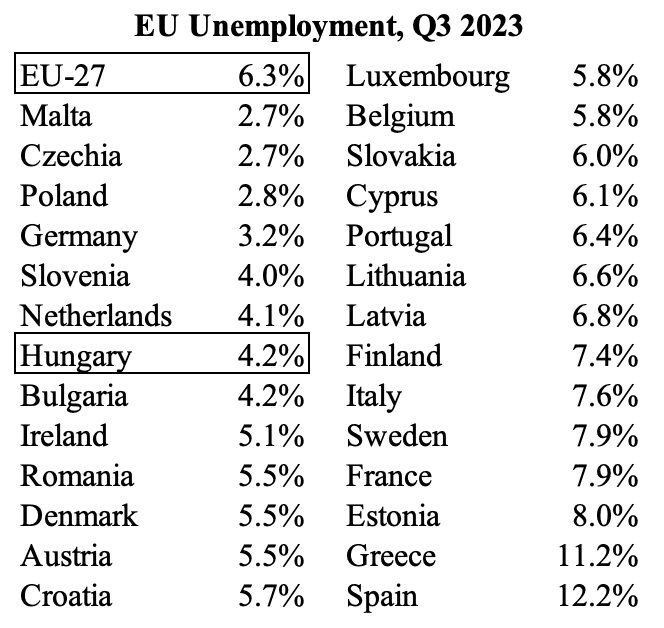

In the first three quarters of last year, the Hungarian jobless rate rose a little bit again, but as Table 1 below reports—and the Monetary Council points out—it remains one of the lowest in the EU:

Table 1

Barring any disruptive numbers for the last quarter of 2023 or for January, there is no immediate risk for an economic downturn in Hungary. This means that there is no macroeconomic threat to the government’s finances, and therefore, there is no risk that the MNB ends up in a position where it is compelled to print money to finance the budget deficit.

As the Monetary Council notes, the Hungarian government debt is moderate, especially compared to that of some other EU members—even members of the euro zone. With that said, the government’s fiscal status is the only point where Hungary could use some improvement. This is not a major problem, but nevertheless one worth noting.

The Fidesz government has a history of well-managed deficits: e.g., in 2017-2019, the average shortfall in the consolidated government finances was 3.8-4.2% of spending. This is a low deficit-to-spending ratio by international comparison. However, while the pandemic necessitated larger budget gaps, the deficit-to-spending ratio has remained elevated even after the economy recovered from the pandemic. In 2022 the government borrowed the equivalent of 11.6% of its spending.

Looking at the quarterly numbers for 2023, the trend is a bit encouraging. In the second and third quarters of last year, the deficit ratios were 6.5% and 8.4% of government spending, respectively.

Given its history of intelligent fiscal management, we can expect the Fidesz government to bring down the deficit going forward. I would encourage them to move a little faster on this: so long as the economy remains strong, tax revenue will continue to pour in at high levels, but even if the MNB is correct in its exports outlook, Hungary cannot entirely evade the repercussions of an international recession. The stronger the government finances are at that point, the smaller the risk for any monetization adventures.

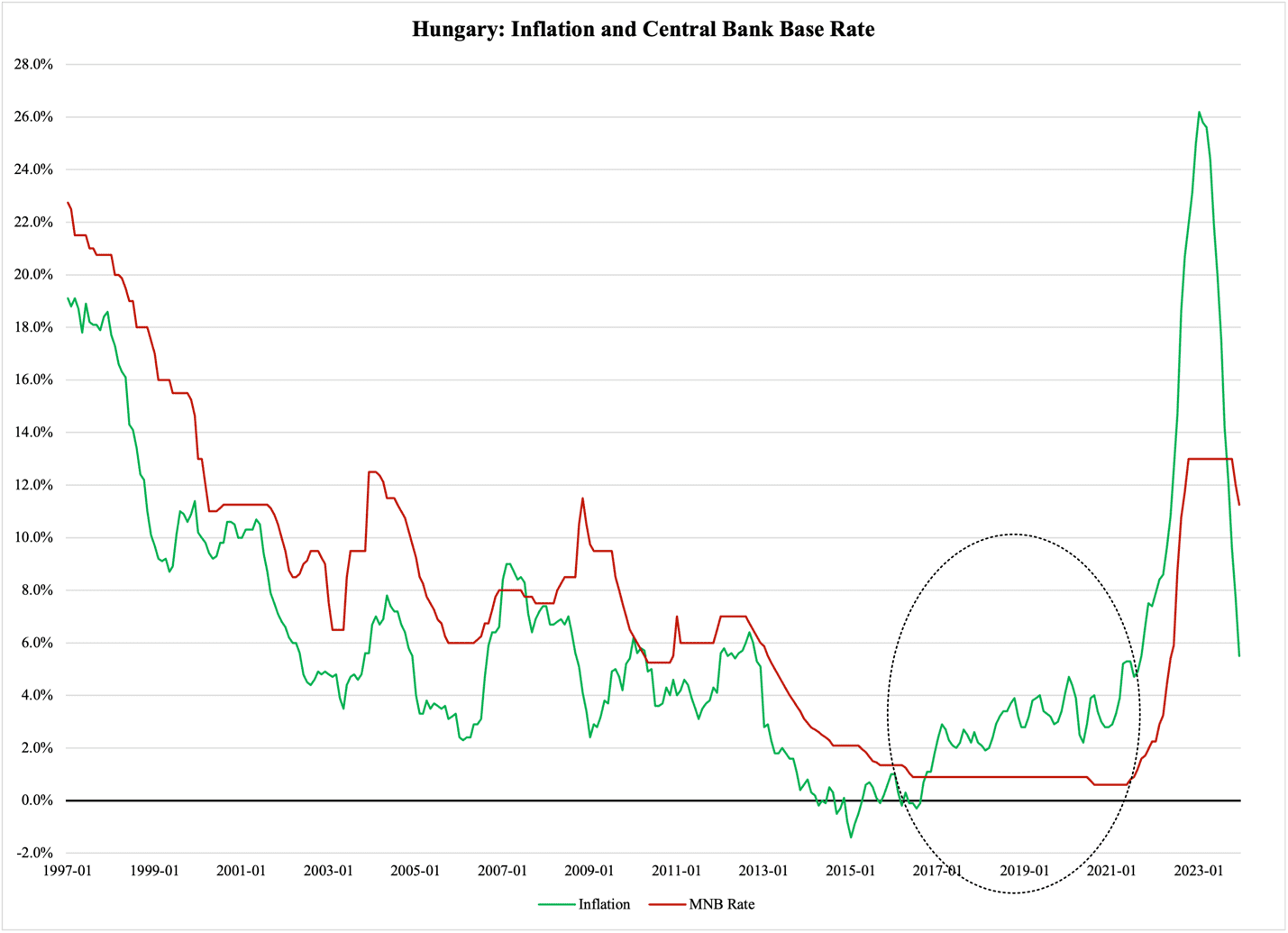

This is not a major problem—it is small but not insignificant. In addition to the government having a good track record on fiscal policy, the Hungarian central bank is also well-run. They have a history of competent monetary policy, especially in terms of managing inflation. Figure 1 reports the MNB’s base rate (red) compared to consumer-price inflation (green), measured according to Eurostat’s HICP index. The central bank did a fine job bringing inflation down in the late 1990s, anticipated and responded quickly to the inflation rebounds in 2004 and 2007, and made the bold but necessary move to raise interest rates in the midst of the Great Recession in 2009-2010.

The only period of concern is that which is marked by an oval:

Figure 1

From June 2016 through July 2021, the MNB kept its base rate below 1%. As Figure 1 shows, inflation began building during this period. It went up from virtual price stability to the 3-4% range.

Unlike its previous responses to inflation, the MNB refrained from tightening monetary policy during this period of time. It is understandable that they kept their rate down during the pandemic, but if they had intervened in 2017 and 2018 to curb inflation, they could have been in a better position when inflation took off in 2022—even if they had temporarily cut rates in 2020.

With that said, when the MNB responded to rapidly rising inflation, it did so with a firm hand on the policy lever and well-managed rate hikes. The fact that inflation is dropping as quickly as it increased is a sign that the central bank did a good job responding to the double-digit inflation episode.

If we assume that the pre-pandemic period of sub-1% interest rates in 2017-2019 was an exception, we have good reasons to believe that the MNB will stick to its guns on inflation. This also means that we can expect them to refuse to monetize budget deficits, thus leaving it to the Hungarian legislature to manage its fiscal balance.

The Hungarian economy remains one of the strongest in Europe. The MNB’s interest-rate cut was a bold but measured policy move. Rather than jeopardizing the fiscal balance of the Hungarian government, this rate cut will likely help the country avoid a deep recession.

Overall, the MNB is one of the best-run central banks in Europe, and in itself a good reason for Hungary not to join the euro.