Last week, I pointed to warning signs in the U.S. debt market, suggesting that investors are growing cautious about Treasury securities.

I am in no way alone in sounding the alarm. Others are pointing in the same direction, including Libby Cantrill and Richard Clarida with the global investment firm PIMCO. In a recent commentary on the state of the U.S. debt market, they explained that

many clients have asked about the sustainability of the path of U.S. debt, whether politicians plan to do anything about it

They also shared their pessimistic outlook:

Absent changes to either mandatory spending or taxes, which we do not see as likely over the next several years, we believe that the market will eventually demand—and earn—a premium for holding longer-dated Treasuries, and that this will lead to a steeper U.S. yield curve over time.

They add that they “don’t believe there will be a fiscal crisis” in America “any time soon.” That sounds comforting, but it is important to keep in mind that PIMCO has some high-caliber employees. Just two examples: Richard Clarida, one of the article authors, is a former vice chair of the Federal Reserve, and their Global Advisory Board is chaired by Ben Bernanke, who ran the Federal Reserve from 2006 to 2014.

With such influential people on their staff, and with an asset portfolio of at least $346 billion, PIMCO simply cannot say anything radical about the state of the market for U.S. government debt. It would create too big of a splash and could even cause unmerited market instability.

At the same time, the very fact that they even mention a fiscal crisis, and that they do so after having revealed that their clients are worried about the future of U.S. Treasury securities, is a blaring siren in the ears of America’s political leadership.

It is not the only one. On February 20th, two days before the PIMCO commentary, the Canadian news daily Financial Post republished a Bloomberg article with a message pointing in the same direction:

Investors are beginning to war-game how the United States Federal Reserve can manage a U.S. economy that just won’t land, with some even debating whether interest rate hikes will be needed only weeks after a steady run of reductions appeared all but certain.

There is a point to this article, beneath the superficial story of how the U.S. economy may continue to do well. This hidden point is that the Federal Reserve may choose not to cut interest rates at all this side of Independence Day. If that does not happen, Congress has to cope with continuing increases in the interest cost of the debt.

There are other reasons why the Federal Reserve may choose not to cut its interest rates, but before we get there, it is worth noting that the Fed may be forced to abandon its planned rate cuts simply because of investor worry over the debt. In that case, the war-gaming investors that the Financial Post refers to will have good use for what they have learned about the Fed’s no-cut policy.

Regardless of why the Fed would choose to keep its federal funds rate unchanged instead of cutting it, their policy decisions would illustrate how inept the central bank is in addressing America’s looming debt crisis. This ineptitude was emphasized by Charles Payne, who runs a major investment-oriented show on Fox Business, when he appeared on Kitco.com on February 26th.

Payne explained that Congress is primarily responsible for the high government debt; although he did take a well-merited jab at the Fed for having facilitated a large part of that borrowing, he also acknowledged the futility of the Federal Reserve trying to discourage more borrowing:

Now we are here at the precipice, you know, of this situation, where [Fed chairman Powell] rightfully acknowledges that there is a problem, but to be quite frank … I don’t see the Federal Reserve doing anything about it. They are playing a role in this, and they are not backing away from this role.

Payne also correctly explained how the U.S. economy has effectively been caught in a public debt trap. Every attempt by Congress to rein in its deficit will have painful consequences for a large majority of Americans.

Alas, that pain is unavoidable at this point. The longer Congress waits, the more painful the fiscal adjustment to a balanced budget is going to be. The fact that Congress continues to wait is frustrating; the alarm bells have been ringing for a good long time now, not just by me and other economists, but by people high within the financial industry who warn of a global walk-away from U.S. debt.

This unwillingness on behalf of our elected officials has now brought us to the point where interest rates may be going up, not down. As the Financial Post/Bloomberg article notes, based on an analysis of derivative markets,

traders have not only removed March as a possibility, but May also looks improbable, and even conviction about the June Fed meeting is wavering

I conditioned my prediction of a March rate cut on there being no earth-shattering news along the way. Technically speaking, no such news has surfaced, but that does not mean the earth has not shattered. At some moment in time, the refusal of Congress to do anything becomes an inflection point of the same significance as an adverse shock to the economy.

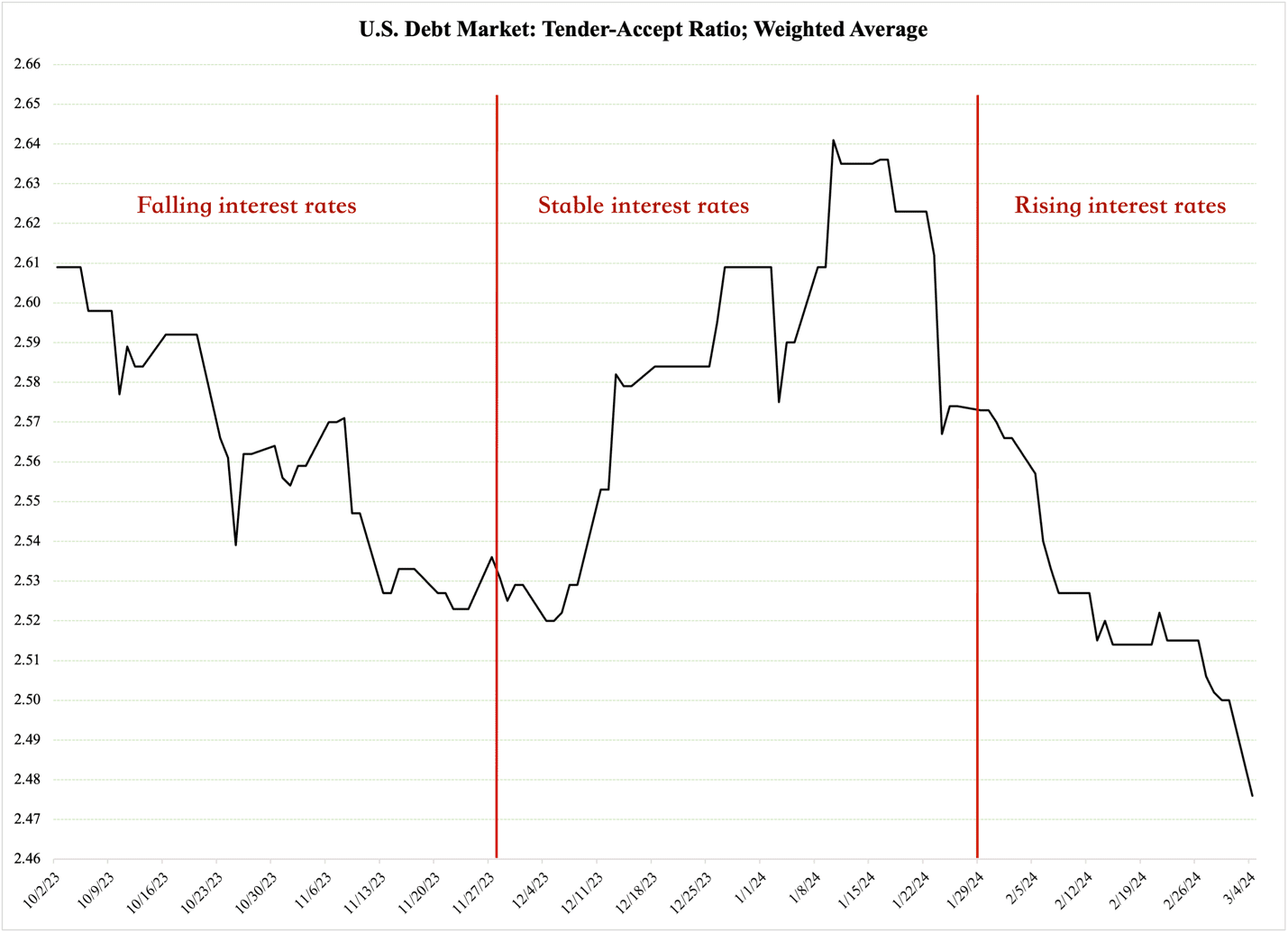

In my two-part analysis last week, I pointed to how two variables signal a slow-moving decline in investor demand for U.S. debt. These two variables are associated with the auctions where the U.S. Treasury sells new debt, the interest rates they have to offer in order to sell all the debt they want to sell, and the so-called tender-accept ratio at the Treasury auctions.

The latter, known simply as the T/A ratio, is the number of dollars investors are offering, or tendering, at any given Treasury auction vs. the amount of debt that the Treasury accepts, i.e., wants to sell. When there is strong investor interest in U.S. debt, the T/A ratio rises; when investors are saturated or when they harbor growing worry about the debt, the ratio falls.

The T/A ratio, which is a weighted average for the entire U.S. debt, fluctuates regularly with movements in the market. Its current value is relatively high compared to where it was in the early months of the 2023 fiscal year. However, as Figure 1 below shows, it has been trending downward since the start of the 2024 fiscal year on October 1st last year.

Repeating a point I made last week,—the decline in the T/A was no problem back in the fall when interest rates on the U.S. debt were also declining; while investors offered less money per dollar of auctioned debt, they did not express concerns over the debt through the yields they demanded.

Falling interest rates were replaced with stability, while the T/A rose. This is how investors exhibit confidence in the market, but given the short duration of the stability phase in Figure 1, it is reasonable to conclude that this was nothing more than the accumulated effects of portfolio realignment among investors.

In the most recent phase in Figure 1, the falling T/A ratio is coupled with rising interest rates. Now investors are showing weakening interest in U.S. debt—and they are doing so through both this ratio and the yield they demand:

Figure 1

The T/A ratio continues to fall, and even though interest rates have been stable over the past week, if there is any movement in the market, it is toward higher rates. Therefore, my warning stands: these numbers corroborate the warnings coming from multiple other sources that investors are having second thoughts about U.S. government debt.

Once that sentiment sets in, the fiscal-crisis clock is ticking. The only thing that can stop it is a strong showing of fiscal courage from Congress.