The European recession that I have been warning about is catching media attention. On Monday, citing the German federal statistics office, the American news outlet ABC reported:

Germany’s economy shrank 0.3% last year as Europe’s former powerhouse struggled with more expensive energy, higher interest rates, lack of skilled labor and a homegrown budget crisis.

Things are getting bad when the fate of the German economy is drawing the attention of the media far away from the country’s borders.

With that said, the report itself is not very good. If we are going to get a good idea of where the European economy in general is headed, we need to get the facts straight. To that point, the Statistisches Bundesamt, SB, makes very little mention of a skilled labor shortage. The only reference to it is in the context of the construction industry:

In the construction industry, deteriorating financing conditions had a particularly noticeable impact on development, alongside persistently high building costs and a skilled labor shortage.

The SB also explains that “weaker domestic and foreign demand … took their toll” on economic activity. This is almost the definition of a shrinking economy, but more importantly: you cannot have a declining GDP and, as the ABC News story alluded to, a labor shortage. An economy with a labor shortage is operating at the very top of its capacity, which means that it is growing rapidly; by contrast, an economy where GDP is contracting has more supply than demand—especially in the labor market as a whole.

Even more importantly: labor shortage does not cause economic recessions. It is as illogical as to claim that the warm temperature of a summer day causes winter.

As the German economy moves deeper into its recession, demand for newly constructed buildings—whether private homes or business facilities—will decline. This in turn will lead to rising unemployment in the construction industry as well as in the economy generally.

In terms of the size of the GDP contraction, the ABC story is again a bit careless with the facts. Back to the SB press release:

[The] price adjusted gross domestic product (GDP) was 0.3% lower in 2023 than in the previous year. After adjustment for calendar effects, the decline in economic performance amounted to 0.1%.

Although I prefer to use GDP numbers that are not modified for calendar effects or seasons, it is nevertheless important to note which calculation of GDP we rely on. Another news source might use the 0.1% number and, like the ABC with the 0.3% number, fail to report exactly what the number means. This creates unnecessary confusion and mistrust in economic information.

As I reported back in November, the German GDP fell in both the second and the third quarters of 2023. This means that the German economy already is in a recession. The big question now is what the German government will do about it and the budget deficits that always come with a recession. They have already felt the sting of austerity despite having suspended their constitutional debt brake.

The debt brake is a tool intended to force the government to minimize its budget deficits and strive to make a balanced budget its fiscal policy norm. When the German Bundestag suspends it, they do it out of concern that the brake would force the German government to raise taxes and cut government spending in the midst of a recession. Such contractionary fiscal policy—known as austerity when applied systematically—aggravates the recession.

Ironically, this raises the question why the debt brake exists in the first place: deficits of the magnitude not permitted by the debt brake only occur in recessions; if the brake is to be suspended as soon as the budget deficit gets big enough that the brake should be used, then what is the point with even having it?

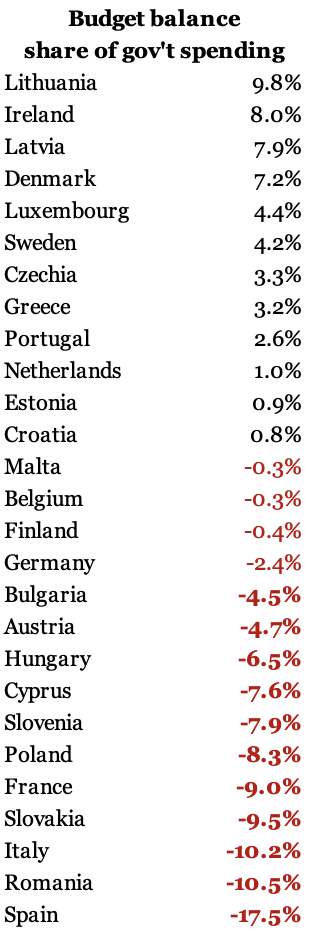

Germany is not the only country that is struggling to balance its government finances. In the second quarter of last year, 15 EU member states had deficits in their consolidated government finances. In eleven of those countries, the deficit exceeded the 3% limit set in the EU’s stability and growth pact (which, as it happens, has also been suspended):

Table 1

This snapshot of public finances in Europe is representative of a trend of growing deficits. These deficits, in turn, will drive lawmakers in most EU member states into a difficult policy dilemma:

In the former case, the government risks turning a recession into something worse; in the latter case, they risk the wrath of investors on the market for sovereign debt.

Neither option is desirable. Once a country gets to the point where debt investors start demanding higher interest rates to buy new debt, the government is forced to do what they did not want to do in the first place. There is nothing more destructive to a peacetime economy than fiscal austerity at the edge of the investors’ knife.

Regardless of whether it is panic-driven or a deliberate choice, austerity will inevitably hurt broad layers of people. In 22 of the EU’s member states, government spends 60% or more of its money on social protection, health care, education, and housing programs.* In Germany and seven other member states, that share is north of 67%.

With such a large portion of the public purse being used to help people who depend on government to make ends meet, the governments of the EU’s biggest welfare states have strong incentives to avoid being caught in a fiscal panic situation. The question is how they are going to avoid that.

—

*) The sharp-eyed reader will note that in the past, I have reported a higher share, in excess of 70%. This number covers a broader definition of the welfare state; the spending share referred to here is based on a narrower, more widely used definition.