Photo: PublicDomainPictures from Pixabay

Good morning, Europe, and welcome to the recession. With three months to go before voters go to the polls to elect a new European Parliament, the only thing growing in the EU economy are the ranks of the unemployed.

On the face of it, things do not look too bad: the total unemployment rate in January for the EU as a whole was 6.3%, up from 6.0% in December and no change from January 2023. The euro zone can even show a slight year-to-year drop in unemployment, from 6.9% to 6.7%.

So why sound the recession alarm bell?

Simple: the EU and euro zone averages obfuscate the actual trends in the economy. Let us start with the actual unemployment rates for January across the EU.

At 12%, Spain had the highest total unemployment rate of all the 27 member states. Greece comes in second at 11.2%, followed by Lithuania (9.0%), Sweden (8.5%), and Finland (8.3%). While Spain and Greece have almost the same unemployment rates in January 2024 as they did a year earlier, the other three top countries have seen their jobless rates rise over the past 12 months.

In total, 17 of the EU’s 27 member states recorded a higher unemployment rate for January in 2024 than in the same month of 2023.

The trend is even sharper among young workers. To date, 22 EU states have reported their youth unemployment rates to Eurostat; of those, the jobless rate among young workers was higher in January 2024 than in the same month last year.

As for actual unemployment rates, Spain is at the top again with 27.8% of the young workforce idling. Sweden is now second at 24.9%, with Portugal (24.2%), Greece (24.0%), and Italy and Luxembourg (22.6%) completing the top five.

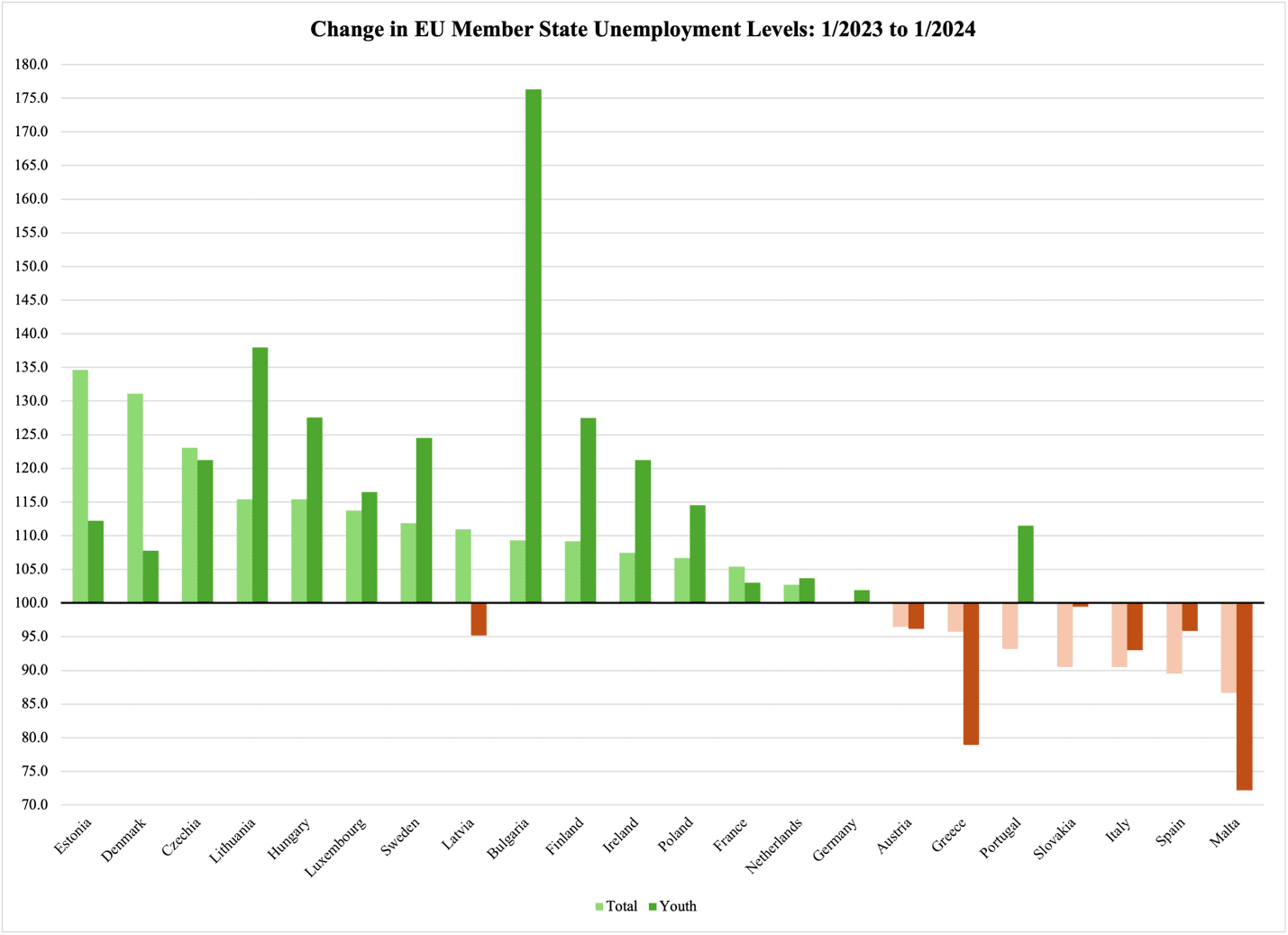

Figure 1 helps us understand how unemployment has crept up over the past year. The index value on the vertical axis illustrates a rise in the unemployment rate (higher than 100) or a decline (less than 100). Light green columns are for total unemployment and dark green columns for youth unemployment; light beige and brown indicate falling rates.

There are 22 countries included, with five excluded because, again, they have not yet reported youth unemployment for January 2024. Of the 22, 14 have experienced a rise in unemployment among the total workforce as well as among the young:

Figure 1

This year-to-year comparison is compelling, not only because it illustrates a reasonably long trend in the economy, but also because it eliminates seasonal variations in the unemployment rate. Such variations are excluded in Eurostat’s parallel database with seasonally adjusted numbers; the problem with those numbers is that they convolute rapid shifts in economic activity. These are shifts that can help us identify, with fairly good precision, when economic trends change.

The current situation in the European economy is a case in point. Let us take a look at a couple of examples to see that the rise in unemployment is not just a seasonal phenomenon, but a real and abrupt macroeconomic shift.

In Finland, total unemployment hovered around 7% through the second half of 2023. In January, it jumped up to 8.3%. This 1.3 percentage-point rise is bigger and happened at a higher level than the same trend a year earlier, when the rate held relatively stable at 6.5% through the second half of 2022 and increased to 7.6% in January of 2023.

The jump in youth unemployment is much more conspicuous: after floating around 13.6% from the summer through December, it leapt to 20.4% in January this year. The corresponding numbers from a year earlier are the much milder 11.9% and 16%, respectively.

The trend in youth unemployment is especially troubling. They are commonly the first to lose their jobs when the economy takes a downturn.

Sweden has a similar, but in some ways even worse problem. After total unemployment averaging 6.9% from June to December 2022, the rate remained at about 7.7% throughout 2023—and jumped to 8.5% in January 2024. Meanwhile, their youth unemployment rate has consistently remained one of the highest in Europe at 21.7% in both 2022 and 2023.

The January 2024 figure is notably higher at 25%.

Denmark has also seen a leap in unemployment. After a rate just below 4.9% throughout 2023, the January 2024 figure came in at 5.9%. On the youth side, their problems began already last year: in the first half of 2023, an average of 10% of young Danish workers were unemployed; in the second half, the rate rose to 12.4%. It ticked up to 12.5% last month.

Just like the Finnish one, the Danish economy exhibits signs of an economic downturn through rising youth unemployment. Both these economies enter this recession from a position of relative strength, which may shorten and alleviate the pain somewhat. Others are not as lucky: Italy and Spain have had high unemployment numbers for a long time, with Spain topping the EU statistics as one of only two countries with a total rate consistently above 10% (the other being Greece).

The Spanish economy consistently leaves some 29% of its young workers unemployed; the Italian figure is 23%. These are bad numbers on any day, but catastrophic if the economy—as is likely to happen—plummets into a deep recession.

Germany, Europe’s largest economy, maintains low unemployment rates: in January, 3.1% of the total workforce was idling while 5.2% of the young were out of work. However, there are hints of trouble on the youth side, with the unemployment rate reaching or exceeding 6% for several months in 2023.

There is no doubt that Europe is entering a recession just in time for its EU election in June. It remains to be seen how high and rising unemployment will affect voter turnout—and who they choose to vote for.