With widespread budget deficits across Europe, the clock is ticking on legislatures to take appropriate action to prevent fiscal catastrophes in the coming recession. The best response is, of course, to bring the recession to a halt before it begins, but if playing fiscal offense is not on the agenda, at least they should take defensive measures to rein in their deficits.

So far, the willingness to respond in either way seems to be absent, with a couple of notable exceptions. One of them is Slovakia.

Reports Bloomberg:

Slovakia’s new government is working on a €1.5 billion ($1.6 billion) package of measures to cut spending and increase revenue next year as it reins in the widest budget deficit in the European Union.

There is a factual error in this sentence. The Slovakian government’s budget deficit, while large, is not the largest (or “widest”) in the EU. According to Eurostat’s database of the fiscal status of European governments, the Slovakian budget deficit is either the second-largest or the fifth-largest, depending on how we count it:

The Slovakian government’s fiscal ranking is more or less a technical point, but it is not irrelevant. When a news story like the one from Bloomberg includes such elementary factual errors, it casts a shadow of doubt over the accuracy of the rest of the story.

With that said, assuming that the rest of the facts in the article are accurate, the Bloomberg story explains:

Finance Minister Ladislav Kamenicky said the government aims for a reduction of the budget deficit by the equivalent of about 1% of gross domestic product annually in the next few years.

If we look at this plan without taking its macroeconomic context into account, it is ambitious but reasonable. To get an idea of how much money this one-percent cut in the deficit means, we add up numbers for the four most recent quarters for which Eurostat provides numbers. From the fourth quarter of 2022 through the third quarter of 2023,

This means that, all other things equal, with an annual reduction of the deficit by one percent of GDP, or €1.2 billion, the deficit would be gone within five years.

According to Bloomberg, the Slovakian government plans to accomplish this by reducing “energy subsidies” as well as by “overhauling the health-care system to boost efficiency.”

It is a good idea in general to reduce energy subsidies; it is not helpful for the economy to have a government that distorts market forces with a multi-layered system of subsidies, benefits, and favorable tax treatments.

There are exceptions, such as when a government is trying to reverse the socially and economically detrimental effects of a socialist welfare state. The Hungarian government is doing just that and having a great deal of success. However, if there is no such ideologically defined, restorative goal behind government spending, the best approach is to reduce the economic footprint of the public sector as far as possible.

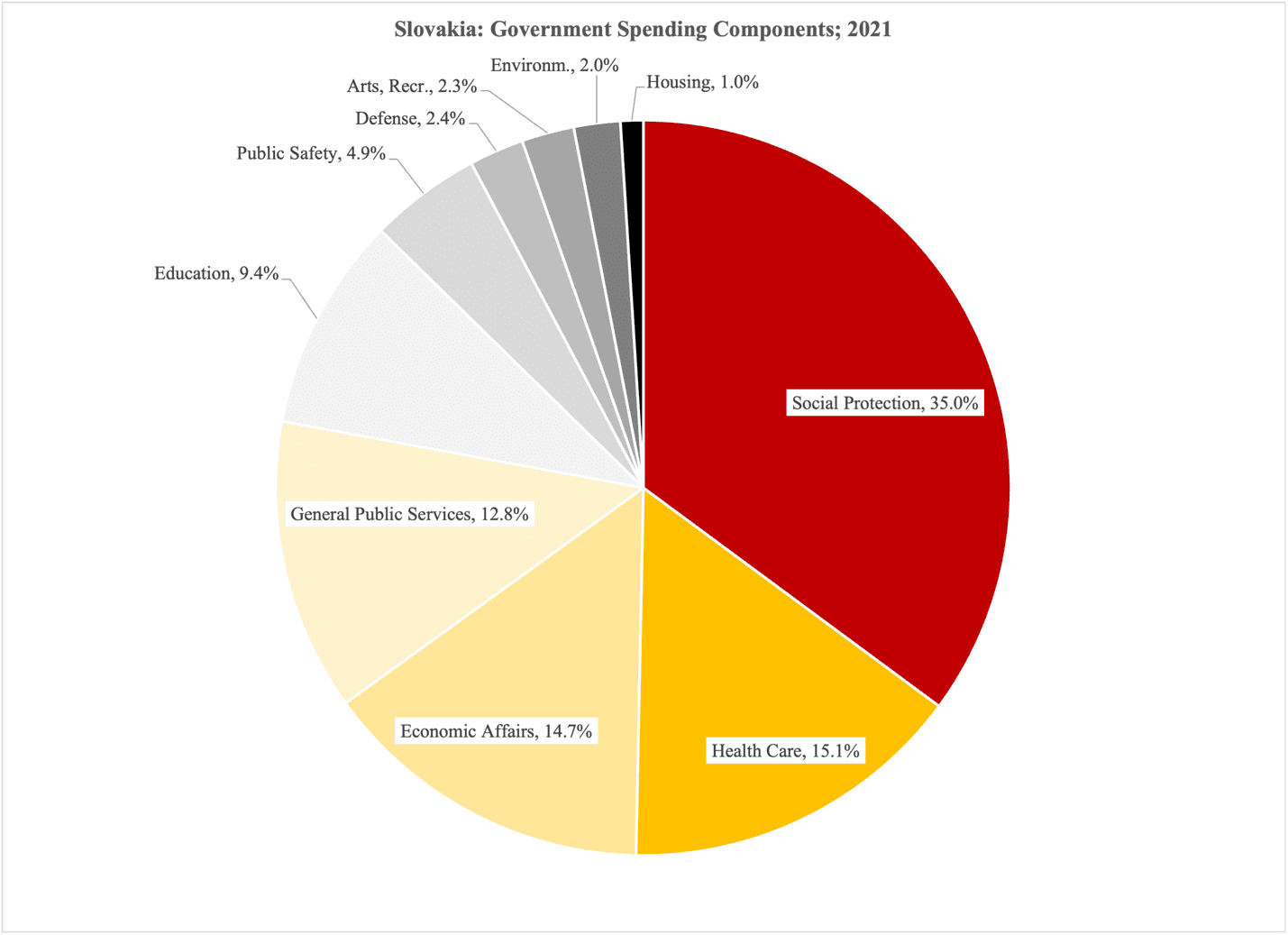

A phasing-out of energy subsidies is well in line with this kind of fiscal policy. So is the idea of efficiency-seeking reforms in the Slovakian health care system. However, as Figure 1 shows, if these two expense items are the only ones that the government in Bratislava is considering, they are making their own work unnecessarily difficult. As Figure 1 shows, health care is nowhere near the biggest share of government outlays:

Figure 1

Energy subsidies count as social protection programs if they are directed to households; if they are doled out to businesses, they would be classified as economic affairs spending.

By trying to close its budget gap while ignoring its social protection programs, the Slovak government is making its fiscal reforms more difficult than they need to be. The nature of social programs is, generally, that they redistribute income and consumption among households, benefitting those with lower incomes at the direct (through taxes) or indirect (no benefits) expense of those with higher incomes.

This is economic redistribution; without going into the details of how the Slovakian welfare state works, there is no doubt that a significant portion of its social benefits are used precisely for redistributing income and wealth. When Eurostat measures the distribution of income using the so-called Gini coefficient, they report that in Slovakia,

The lower the coefficient, the more evenly income is distributed among the citizenry. In other words, the Slovakian welfare state reduces market-based income differences by almost 46%. This is well in line with the Nordic welfare states.

When government plays such a significant role in rearranging economic outcomes in the economy, it also assumes responsibilities vs. its citizenry. Those who benefit from the redistribution programs get used to receiving those benefits on a regular basis; not only do they plan their monthly expenses based on the regularity of those benefits, but they also reduce their workforce participation—qualitatively or quantitatively—simply because they do not have to work for a portion of their earnings.

This redistributive function of government programs is closely linked to the fiscal problems that plague virtually every welfare state in the world: recurring budget deficits. This problem is exacerbated by slow GDP growth; since the second quarter of 2022, the Slovakian economy has been growing at an annual rate of 1.2%—far below what is needed to sustain a welfare state over time.

The government of Slovakia deserves credit for wanting to implement some spending reforms in order to rein in its budget deficit. If they could avoid tax increases, it would make their case stronger, but even more important is the need for structural, sustainable spending reforms that permanently reduce the size of government. When taxes and public-sector outlays increase above 40% of GDP, there is a permanent slowdown in economic growth—which in turn contributes to a weaker government budget.

Structural spending reforms will necessarily target the redistributive nature of the Slovakian welfare state. Such reforms require a level of determination and political endurance that Europe so far has only seen in Hungary.