Watching Europe’s economy today is like watching an old Alfred Hitchcock film in slow motion. You know where the story is taking you, the slow pace is agonizing, and you know there is nothing you can do about it, except to try to inform those in power.

Sweden is the latest example of a country that is slow-walking itself into a new economic crisis. The most apparent problem is high and rising unemployment, but the jobless numbers are only the surface.

In December, 22.6% of all young workers in Sweden were unemployed. This put Sweden in 4th place in the EU, with only Spain (27.1%), Greece (24.3%), and Portugal (23.6%) ahead.

In January, the Swedish youth unemployment rate increased to 24.9%, elevating Sweden to second place behind Spain.

Looking at unemployment among the workforce as a whole, the Swedish January rate of 8.5% is lower than Spain (12.0%), Greece (11.2%), and Lithuania (9.0%), but ahead of every other EU member state. Just as with the young workers, the trend here is not positive.

What makes the Swedish situation so frustrating for an economist is that the cause of the high unemployment is not some cyclical downturn in economic activity. Sweden suffers from a deep, structural economic problem that no government, Left or Right, seems to be able to grasp, let alone solve.

I pointed to this problem already in December 2022, when I issued an obituary over the Swedish economy. In July last year, I explained how the domestic sector in the Swedish economy has been starved at the expense of government-favored exports. Unlike other countries with strong exports—Hungary comes to mind—the Swedish economy exhibits no spillover effects from exports to the domestic economy.

For reasons I will elaborate on in a minute, this inevitably leads to economic stagnation.

This past December, I warned that rising taxes were contributing to the persistently high Swedish inflation rate. According to Statistics Sweden, inflation in February was 4.5%. Combined with rising unemployment, this spells stagnation—a phenomenon that Sweden last encountered in the early 1990s.

Since I issued my first warning about the structural flaws in the Swedish economy, more than a year has passed, and there are no signs that the economic policy wonks in Stockholm are any closer to comprehending the problem. Apparently, they need to hear the same message over and over again.

The most pressing consequence of the structural flaw is that the Swedish economy is losing all its drivers of economic growth. For the past 30 years, the main source of that growth has been exports: since the implosion of the Swedish krona in the early 1990s, the sales of goods and services to other countries have become an increasingly dominant part of the economy.

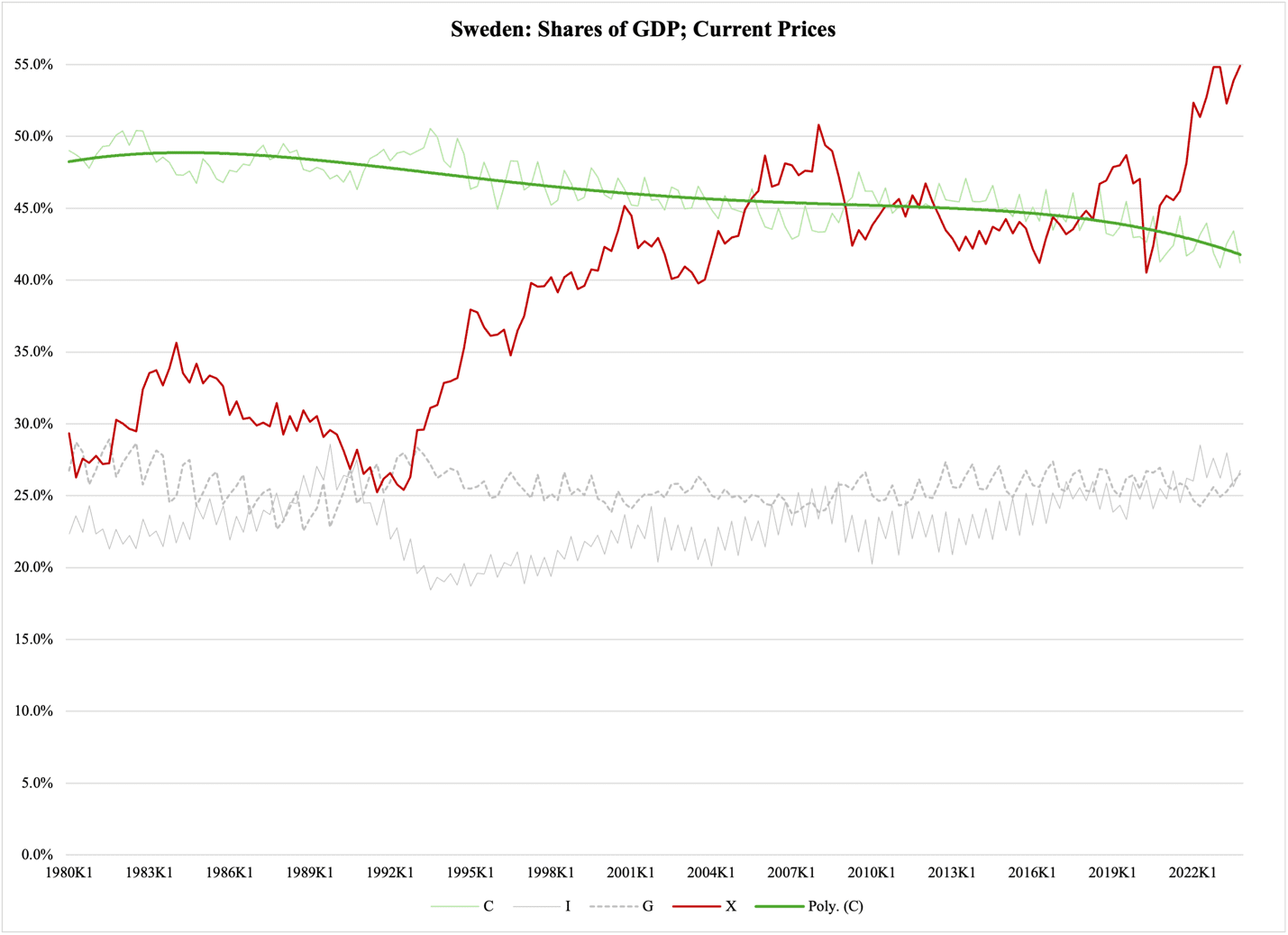

Figure 1 reports the shares of GDP for exports (red line) and private consumption (green). The other two economic activities reported in Figure 1 are government spending, G, and gross fixed capital formation, or investments, I.

As exports have become a bigger and bigger share of the economy, private consumption has gradually become less significant:

Figure 1

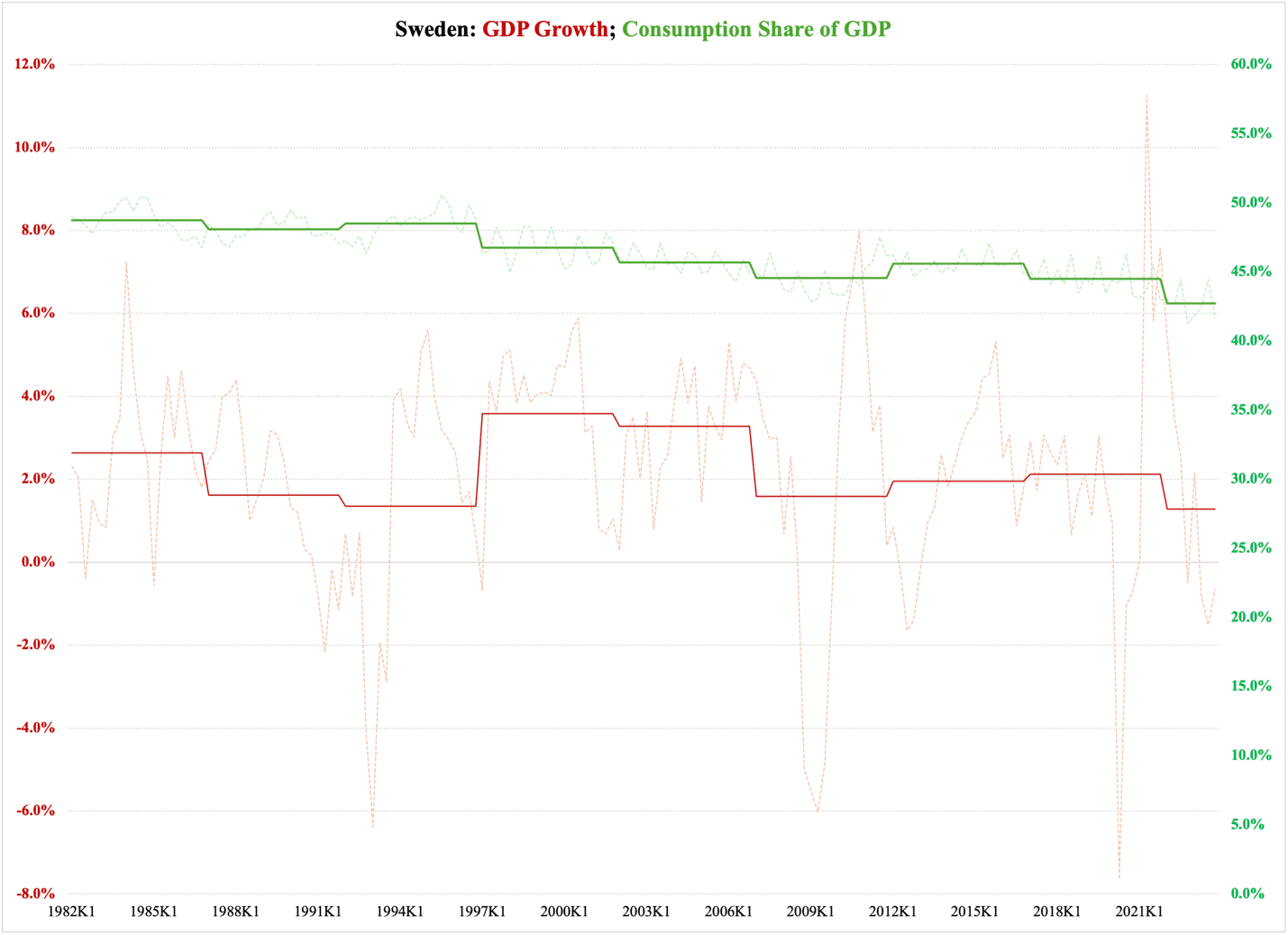

There is nothing wrong per se with strong exports. It becomes a problem when these exports do not pull the rest of the economy up. Figure 2 reports five-year averages for private consumption and GDP growth. As the private consumption share of the Swedish GDP declines (green), so does the GDP growth rate (red).

Figure 2

Sweden experienced a boost in GDP growth in the mid-1990s, when the export boom (as seen in Figure 1) generated a rebound from a deep and protracted economic crisis. However, that boom was short-lived: the larger exports volumes were not of the technology-leading kind that forayed into new markets. Thanks to the weakened Swedish krona and an otherwise exports-favoring economic policy, Swedish exports were still to a large extent centered around the same natural resources and manufactured products that the country was exporting back in the 1960s.

As a result of growth in old-tech exports, there was no new innovations spillover from exports to the domestic sector. This was bound to cause problems; in order to stay competitive on the export markets, big exporters always have to rely on high and steadily growing labor productivity.

This applies to the economy as a whole: steadily rising labor productivity is essential if an economy so dependent on exports will be able to

a) maintain its edge on the exports markets, and

b) enjoy any kind of increase in its standard of living.

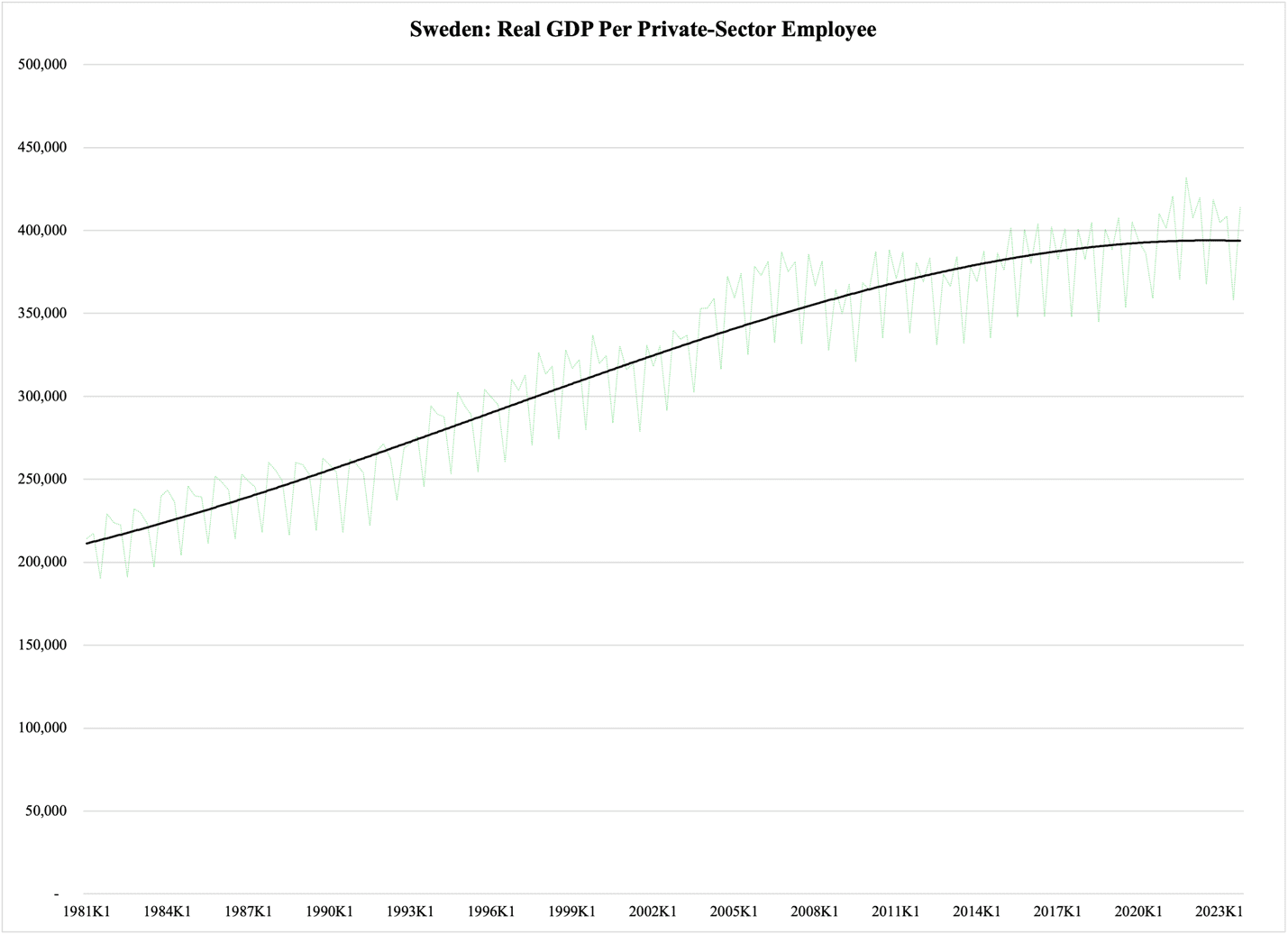

Unfortunately, the Swedish workforce has become less productive in recent years. The most obvious way to illustrate this is to divide the country’s GDP (adjusted for inflation) by the number of workers in the private sector. Figure 3 reports the result, which is more than a little troubling for the Swedish economy. From the 1980s through the 2000s, workforce productivity improved steadily; in the past ten years, though, it has flattened out.

Figure 3

There are several problems with flatlining labor productivity; the three most important ones are:

To start with the last point, if labor productivity continues along its flattened trajectory, higher-tech Swedish exports will lose out to global competition. Increasingly, exports will be dominated by lower-tech products, which require a relatively less skilled workforce. This, in turn, reinforces the stagnant nature of labor productivity; the vicious circle eventually leads to industrial stagnation.

The other two problems with flat-lining labor productivity are related, especially if the tax system relies heavily on personal income and private consumption as revenue sources.

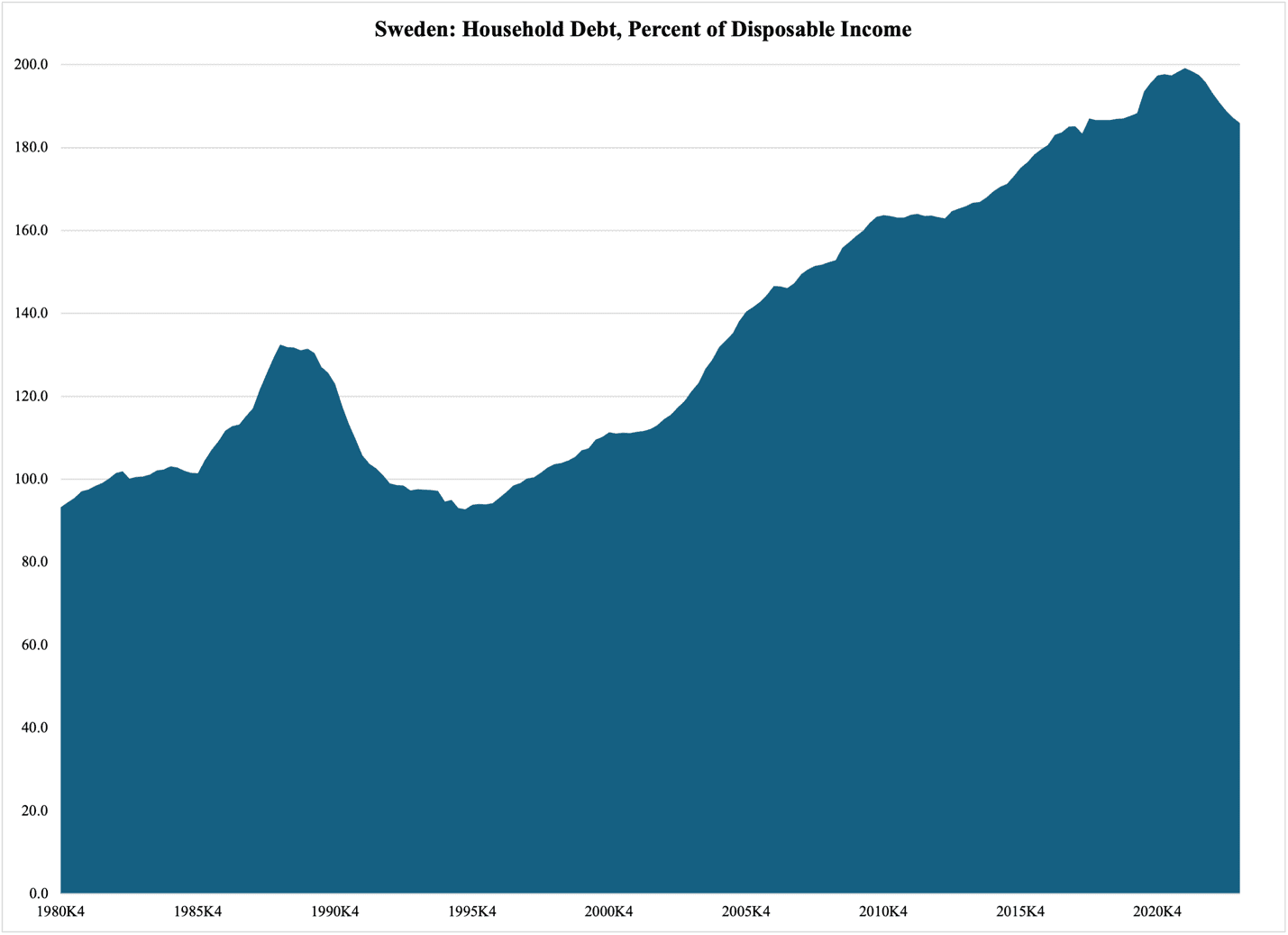

In Sweden, the last ten years’ worth of stagnating productivity have been mirrored in the rise in household debt:

Figure 4

The most recent decline in household debt relative household income (the downslope at the end of Figure 4) is a welcome consequence of changed rules for mortgage amortization. However, it also means that Swedish households are less able to use debt to fund private consumption. The long-term borrow-to-spend habit may be broken, but it has not been replaced by a corresponding rise in household incomes. As a result, private consumption stagnates, thus perpetuating the stagnant nature of the Swedish economy as a whole—and a slow erosion of the tax base.

There are ways to break this pattern of economic flatlining. Next week, I am going to explain in detail how this can be done.