On Wednesday, December 13th, the Federal Reserve will announce its latest monetary policy decision. The big question is whether or not their policy-making board, the Federal Open Market Committee, FOMC, will raise their federal funds rate or keep it constant.

Given the current state of the U.S. economy, a rate cut is ruled out. There will be no rate cuts before March, but possible in the second quarter of 2024.

The most likely outcome of the pending FOMC meeting is that they will decide not to raise the rate. I would like to see a 0.1% increase, but if the choice is between a 0.25% hike and no hike at all, an unchanged rate is more probable than a higher one.

In an interview recently, Michelle Bowman, a member of the FOMC, explained that this committee meeting is held at a time when the economy is unusually difficult to assess. She leans toward a rate hike but could be swayed in favor of a constant rate by, e.g., the slow but continuing decline in inflation.

The Federal Reserve has two policy goals: low inflation and full employment. To achieve the latter, the Fed has to stimulate the economy to good growth rates, but at the same time, if the economy grows too fast, there is a risk of demand-driven inflation. From time to time, this creates tension between the two policy goals, especially when GDP reportedly is growing at very high rates.

The latest release on GDP numbers from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, BEA, suggests that this policy tension may be becoming a reality. With the astounding growth number of 5.2%, adjusted for inflation, the BEA report could be construed as a case for the Fed to raise its interest rate.

Fortunately, there is currently no risk that GDP growth should cause inflation. If the FOMC members have done their homework—and we can safely assume that they have—they will know that the 5.2% growth rate is a pointless number.

There are two ways to explain why it is pointless, the first being addressed by Vance Ginn, chief economist with the White House’s Office of Management and Budget under President Trump. Ginn makes some good points about how government spending plays a significant role in driving up GDP growth to 5.2% per year. Government, Ginn explains, does not add any value to the economy—it only redistributes value that has already been produced—which in reality means that we should reduce the GDP growth number by the government’s contribution.

The second explanation of the pointlessness of the BEA’s 5.2% number is based on the method that the agency uses to calculate the number. This number is the inflation-adjusted growth rate in the U.S. economy from the second quarter this year to the third quarter. In other words, it is not the annual growth rate, which happens to be the customarily used number when economists track GDP growth over time.

The BEA’s 5.2% number is the so-called “annualized” growth rate. This number is found according to an awkward calculation method that I explained back in May. It is not the actual annual growth rate in GDP for the third quarter—it is a hypothetical rate.

Here is how it works: first, you calculate how much inflation-adjusted GDP grew from the second quarter to the third, and then you multiply that growth rate by four. This means that you take the growth rate for one quarter and pretend that it is the growth rate for four quarters, i.e., one year.

This is how the BEA arrived at the 5.2% GDP growth rate.

Sounds confusing? That is because it is confusing. This so-called annualization serves no meaningful purpose for economists. All it does is confuse the public—and people who make economic policy decisions.

Suppose the members of the FOMC took this 5.2% number seriously. They would go into inflation panic and slap a major rate hike on the U.S. economy.

Fortunately, this will not happen. The FOMC members are unlikely to use the annualized BEA numbers and instead rely on the actual GDP numbers, which are found in the BEA’s National and Income Product Accounts tables 8.1.5 and 8.1.6. In these tables, we find GDP figures that are neither annualized nor adjusted for seasons. Table 8.1.5 has GDP figures in current prices, while they are adjusted for inflation in 8.1.6.

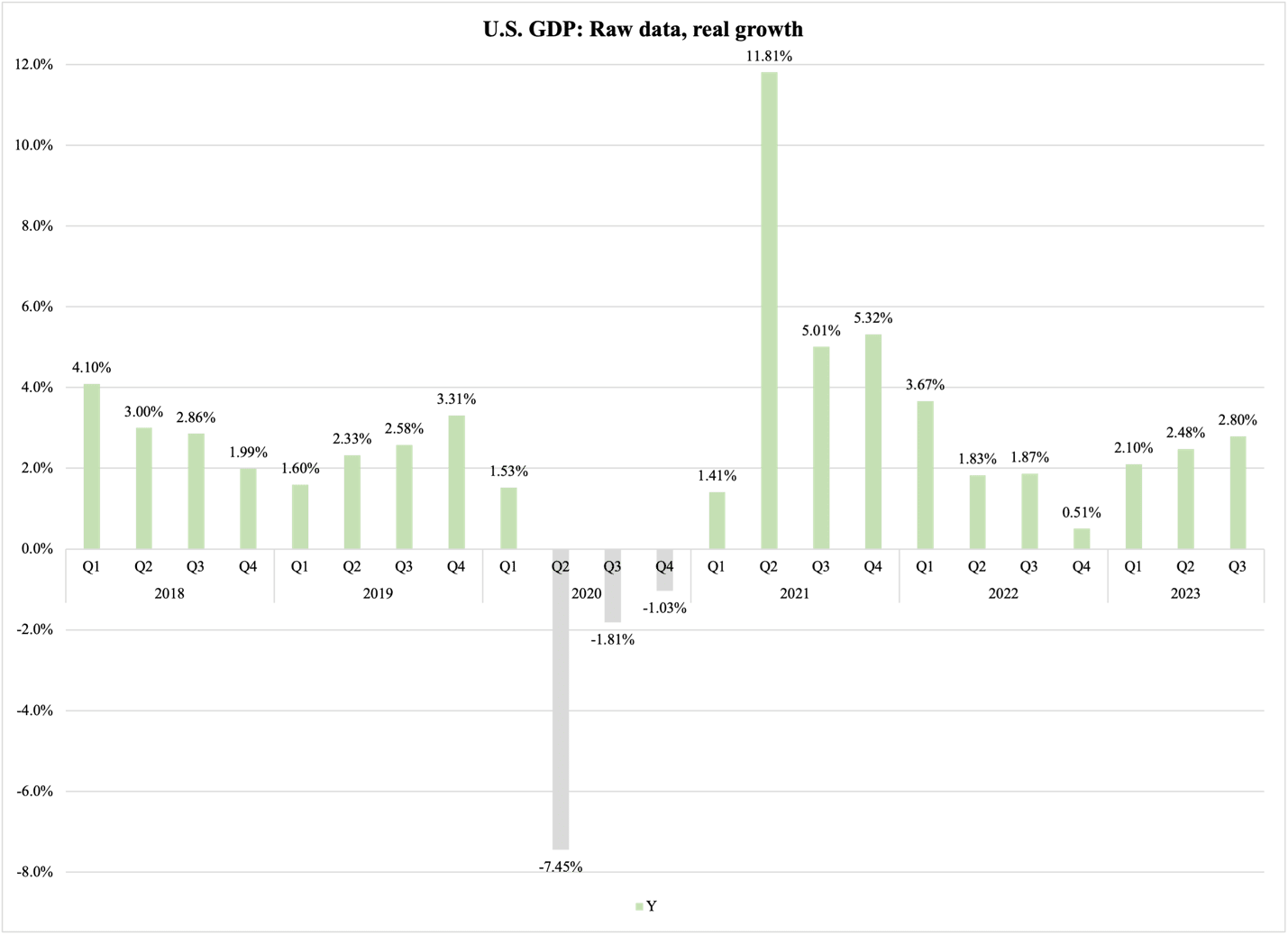

Based on these ‘raw’ GDP figures, we can calculate the actual growth rate for the third quarter. Since it is pointless to look at quarter-to-quarter growth, we compare inflation-adjusted GDP in Q3 of 2023 to the same number for Q3 in 2022. Suddenly, the real GDP growth rate is a lot more modest: the U.S. economy grew at 2.8% in the third quarter of this year.

As Figure 1 shows, going back to 2018, this is still a decent growth number, but for those who know the history of inflation in the U.S. economy, this number is nowhere near enough to cause inflation panic at the Federal Reserve:

Figure 1

If the members of the Federal Reserve’s FOMC use these actual GDP numbers, instead of the hypothetical annualized figures, they will very likely conclude that there is no imminent growth-driven inflation pressure in the economy.

There is one more point to be made about using the correct GDP numbers. If we calculate inflation based on the annualized figures according to this formula,

then it looks like U.S. inflation is currently at 4%. However, if we use the same formula on the actual GDP numbers from tables 8.1.5 and 8.1.6, the rate is only 3.16%.

It has been said that there are lies, damned lies, and statistics. I sometimes wish those who produce statistics would not be so quick to make this aphorism look like truth.