Europe and America keep waiting for lower interest rates—and the deeper we move into 2024, the longer the wait seems to get.

On Wednesday, March 20th, the Federal Reserve decided to keep its policy-setting federal funds rate unchanged. The Bank of England made a similar decision the day after. Both these central banks are waiting for inflation to settle at around 2% per year.

The eyes of analysts and commentators are now turning to the European Central Bank, which is holding its next policy meeting on April 11th. The general idea is that with euro zone inflation coming down reasonably well, they could possibly cut their interest rates at that meeting; if not then, definitely at their meeting in June.

I would like to throw some cold water on those expectations. I agree that there is a chance of a rate cut in June, but the probability of it is not much more than 50%. There is one reason for this: runaway deficits in government budgets, first and foremost the federal budget here in the United States.

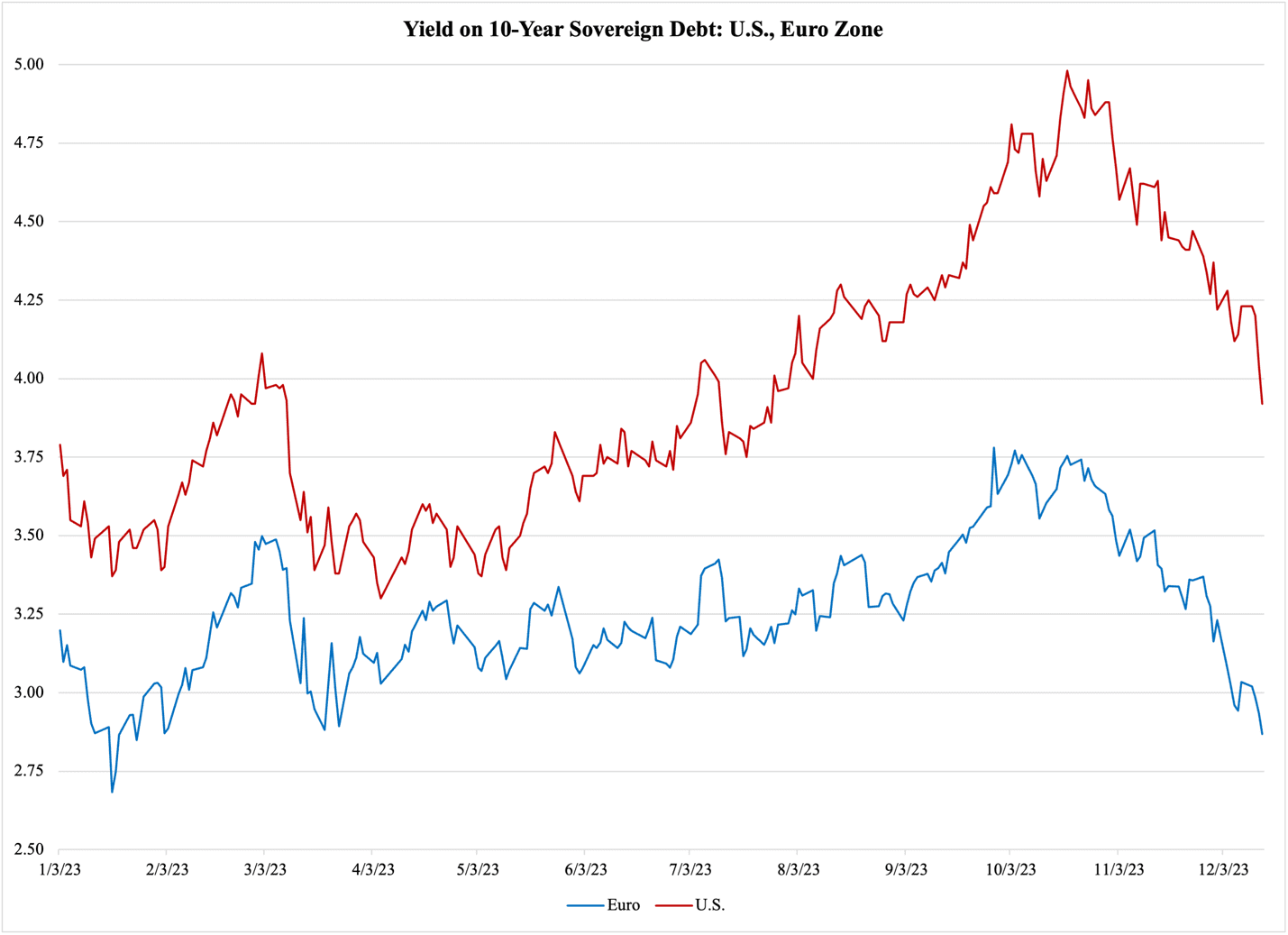

As much as the ECB would like to portray itself as a strong, independent monetary institution, in practice, its policy decisions follow those of the Federal Reserve. European interest rates are closely linked to their U.S. counterparts, especially on sovereign debt. As an example, behold Figure 1, which reports the market yields in 2023 on ten-year treasury notes from the U.S. and the euro zone:

Figure 1

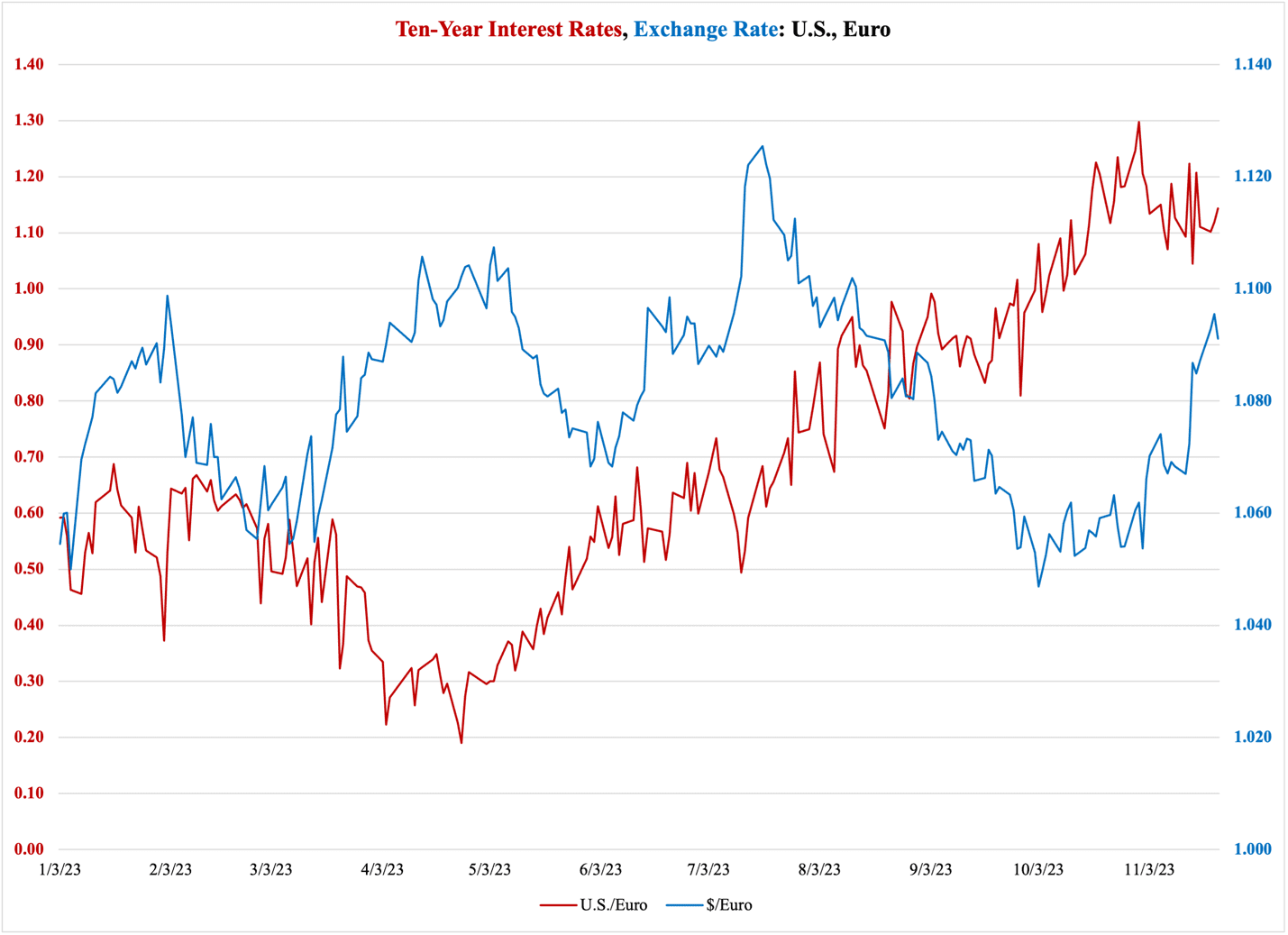

The euro-dollar exchange rate is also tied to the variations in debt-market interest rates. Figure 2 below compares the interest rate gap between the two treasury securities from Figure 1 (red) to the euro-dollar exchange rate (blue). When U.S. interest rates rise a little bit relative to their euro-denominated counterparts, the dollar weakens vs. the euro, thereby offsetting the gains, and vice versa:

Figure 2

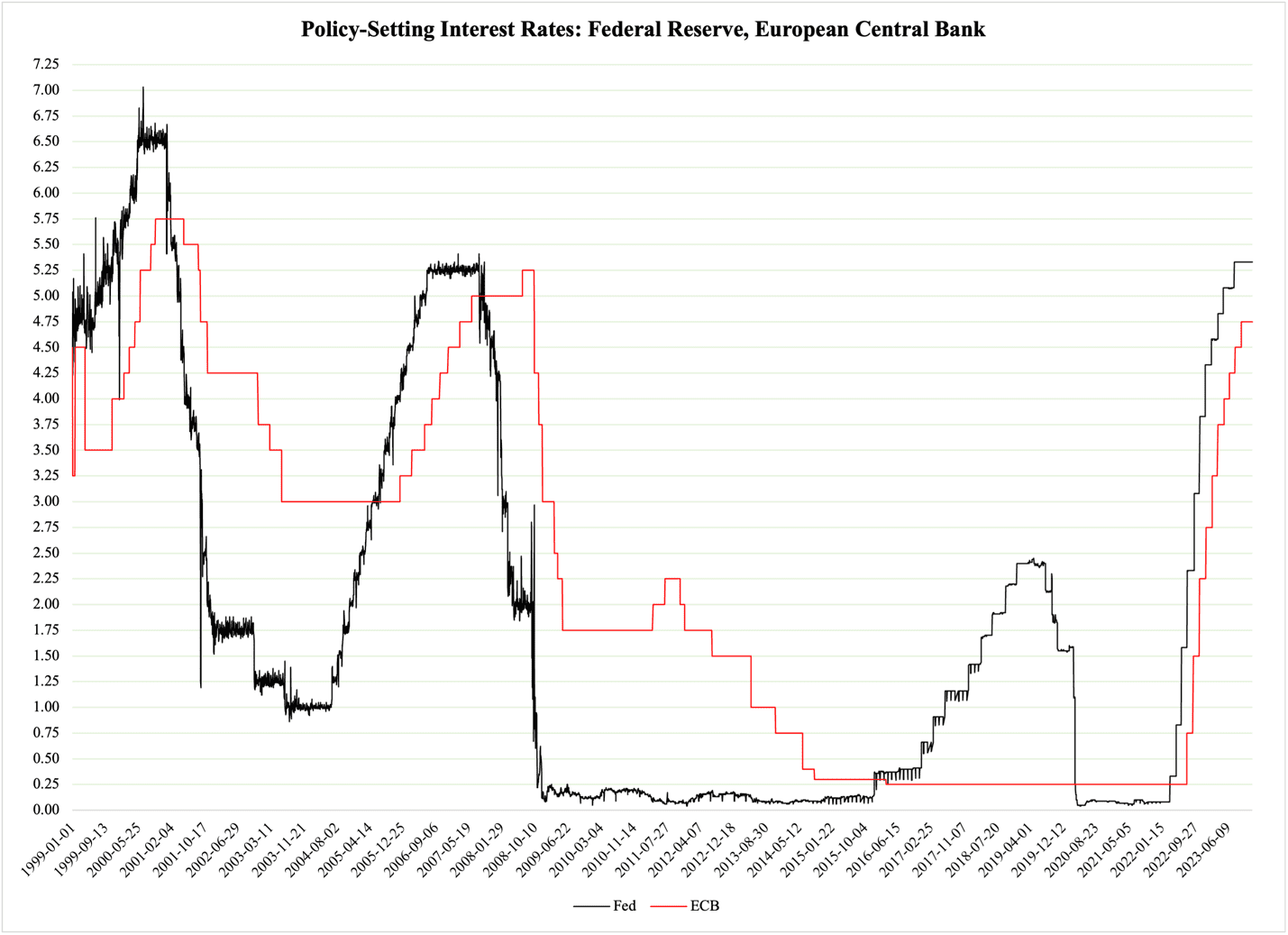

This tight connection between the two markets for sovereign debt is also exhibited in the policy decisions by the two central banks. Figure 3 reports the Federal Reserve’s funds rate (black) and the average of the ECB’s three policy-setting rates (red):

Figure 3

The only time the ECB has not followed the lead of the Federal Reserve was when Janet Yellen took over as Fed chair in 2016 and began rolling back her predecessor Ben Bernanke’s massive money-printing program, often referred to as “quantitative easing.” Other than that, the ECB has, with varying lags, adjusted its policy rates to the Fed’s leadership.

For precisely this reason, it will require extraordinary circumstances for the ECB to take the lead on cutting policy-setting rates. Therefore, the prospect of a European rate cut in June hinges a great deal on whether or not the Federal Reserve plans a cut at its meeting the same month. Since the ECB’s policy meeting is planned for June 6th and the Fed’s Open Market Committee meets on June 11-12th, an ECB rate cut would practically give away that the Fed will cut their funds rate the following week.

However, if history is any guide, as Figure 3 shows, the Fed is likely to cut its rate first. It is unlikely that the Fed will make any such move at its April 30th-May 1st meeting, especially given the tough talk on rate cuts that the Federal Open Market Committee included in its statement on March 20th. Therefore, the ECB will either have to break with 25 years of tradition and precede the Fed with a rate cut, or it will wait until its July 18th policy meeting.

Listening to ECB chair Christine Lagarde, it sounds as though her central bank is not in any real hurry to cut rates; if they do one cut, it might take a while before another one is delivered.

All the leading central banks eagerly talk about inflation as the lead variable for their monetary policy decisions. However, underneath the discussion about whether or not price increases will return to 2% per year, lies a simmering worry about government finances—especially here in the United States.

Officials from the Federal Reserve are completely tight-lipped on the federal budget. However, as I have reported previously, we have heard some real concerns from the private banking sector, which is not a coincidence. Such worries do not show up in statements from bankers just because America’s financial institutions suddenly woke up one morning and saw the budget deficit for the first time. On the contrary, those statements are carefully orchestrated information ‘pointers,’ very likely planted by the Federal Reserve as a way to let people on Capitol Hill and in the White House know about the Fed’s worry.

This worry, in turn, signals that the Fed is going to be very reluctant to participate in another round of so-called quantitative easing, or monetization of budget deficits.

On March 20th, another deficit bomb dropped that could spell doom for future interest rate cuts. The Congressional Budget Office, CBO, an institution under Congress that exists solely to monitor the U.S. government’s fiscal status, released a long-term outlook on tax revenue and spending. The outlook stretches all the way to 2054, which takes away some of its value (economists can barely forecast their own dinner tomorrow), but its statements on the steady deterioration of the government’s fiscal status are nevertheless compelling.

Already in the second paragraph of Chapter 1, after a summary of the outlook on the federal debt, the report explains:

Such large and growing debt would have significant economic and financial consequences. Among its other effects, it would slow economic growth, drive up interest payments to foreign holders of U.S. debt, heighten the risk of a fiscal crisis, increase the likelihood of other adverse outcomes, and make the nation’s fiscal position more vulnerable to an increase in interest rates.

This is a rare and prominent marker from the CBO. The explicit use of the term “fiscal crisis” is a game changer insofar as the outlook on the federal budget is concerned. Up until now, it has been virtually an unwritten rule that nobody, be it from the legislative or executive branches of the U.S. government, utter a word about the risk of fiscal crises. They have all been beholden to the perception that the credit status of the U.S. government is impeccable (even as its credit rating is no longer top-notch), which in turn has led the leaders in Congress to believe that they can pile up an infinite amount of debt without the slightest negative reactions from sovereign debt investors.

With the CBO warning following the debt concerns from the financial industry, the Federal Reserve is in an increasingly confident position to start using the federal government’s enormous budget deficit as a reason to postpone cuts in its federal funds rate.

One of the consequences of such a postponement would be that the ECB may have to do the same.