Photo: Montecuccoli07, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

For every day that goes by, Sweden takes another step closer to euro membership. This is not an open, formal policy of the government; the current center-right coalition, which has no real problems with a euro membership, relies critically on the Sweden Democrats (SD) for a parliamentary majority. The SD are still opposed to a euro membership and do not seem ready to change their minds any time soon.

The progress toward Swedish euro accession is instead driven by seemingly anonymous economic forces, over which nobody seems to have any control.

To see how this works, let us start with the announcement on Wednesday, March 27th by the Swedish central bank, the Riksbank, to keep its governing interest rate unchanged at 4%:

The inflation is moving toward stability around the [Riksbank’s] goal, but the inflationary pressure is still a bit elevated. The board of directors has therefore decided to leave the governing rate unchanged at 4%.

This decision was a bit surprising; unlike most other countries in Europe, Sweden was ready for a rate cut. According to Eurostat’s consumer-price-based HICP inflation index, the rate of price increases was 9.7% in February 2023 and only 2.6% in the same month this year.

The decline has not been straight: after having dropped to 3.7% in September, it rose again to 4.0% in October, only to fall to 1.9% in December. This year, it has been at 3.4% and 2.6% in January and February, respectively. Nevertheless, inflation is down to completely manageable levels and closing in on the Riksbank’s goal of 2%. Much like the Polish central bank did last year, they could have chosen to strike a prudent policy balance between inflation and other macroeconomic priorities.

Those other priorities should play a bigger role for the Riksbank than they currently do. Sweden has been moving into stormy economic waters for some time now, in part because of structural economic problems that have weighed down on the economy for decades. The economic slowdown shows itself in the unemployment rate, which was 8.5% in January and February. This is one of the highest rates in Europe.

Despite the combination of moderate inflation and high unemployment, the Riksbank refused to cut its governing interest rate. As with other central banks who refuse to do the same—including but not limited to the Bank of England and the ECB—there are other variables to take into account. Specific to Sweden is the problem of the unending weakening of the Swedish krona, primarily against the euro.

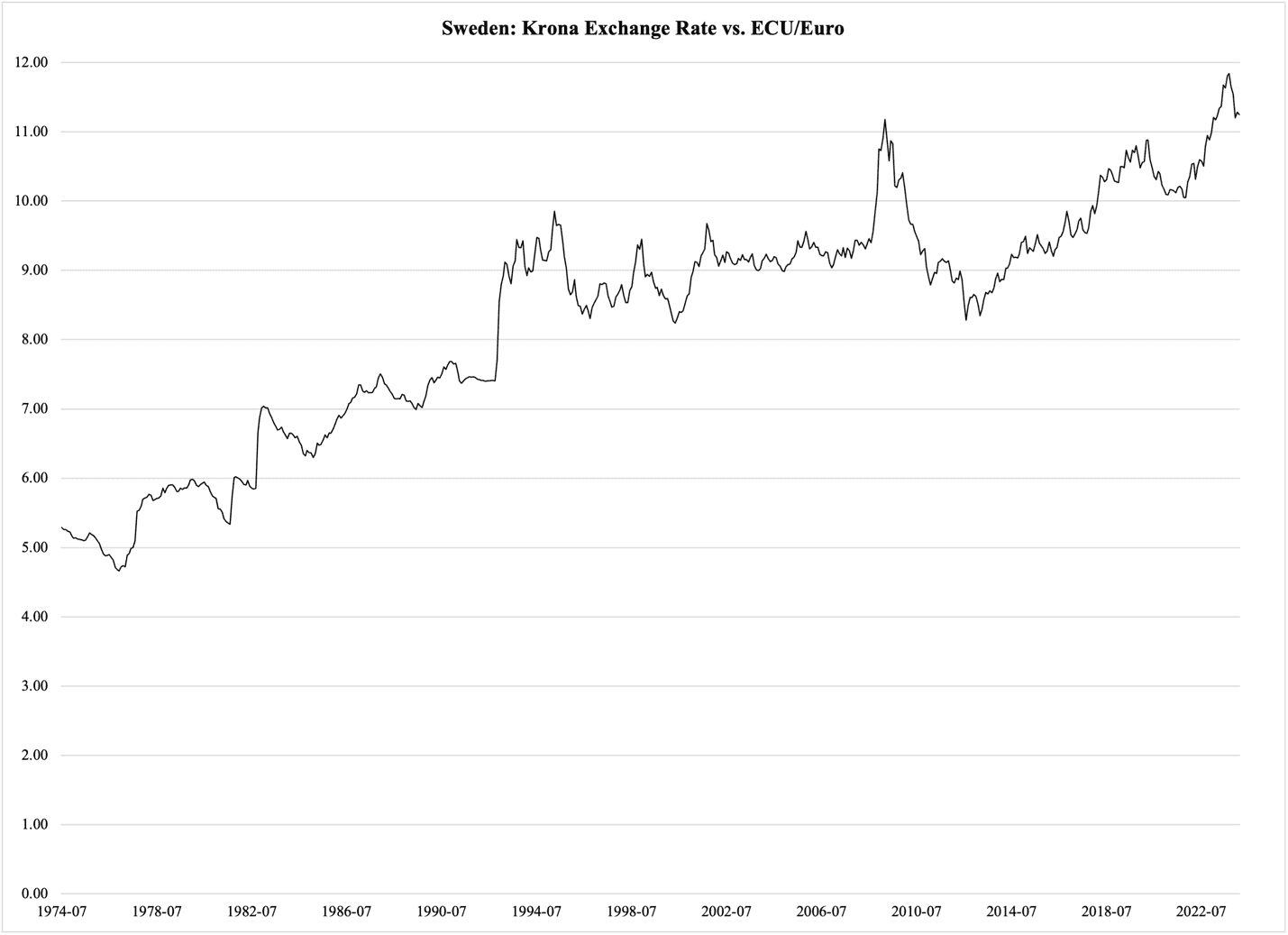

In the past two years, the Swedish krona has depreciated by nearly 7% vs. the euro, but as Figure 1 reports, this is not a new process. Based on an index for the ECU, the non-minted European Currency Unit that preceded the euro under European Communities, Eurostat reports a decades-long problem with the krona’s value. Figure 1 has the story:

Figure 1

The comparison over time is not entirely fair, of course, since the euro was not minted until the turn of the millennium. However, Eurostat’s methodology harmonizes the preceding period with the euro period to the point where the comparison is at least indicative of the trend in a currency’s exchange rate.

There are several problems with a nation’s currency weakening, one of them being that the economy imports inflation with its purchases of goods and services from abroad. A car that costs €30,000 will be priced at SEK270,000 in Sweden at an exchange rate of SEK9 per euro. At SEK11 per euro, the Swedish price rises to SEK330,000, while remaining the same in euros.

To the detriment of the Swedish economy, the krona has been weakening ever since the mid-1970s. Until the fall of 1992, the Riksbank maintained a fixed exchange rate, though they did make a series of managed devaluations of the krona in the years 1977-1982. The fixed exchange rate ended in the fall of 1992, after which the krona went through a period of turmoil.

It eventually stabilized for a bit over a decade at around SEK9 per euro. This was due in good part to an inflow of foreign investment money to Sweden, whose real estate and stock markets were considered bargain investments at the time.

After the 2008-2010 recession, Sweden again found itself wrestling with a sustained value deterioration of its currency. There seems to be nothing stopping this, which is an important reason why the Riksbank is reluctant to cut its interest rate. A cut would encourage investors to sell assets held in Sweden, exchange their kronas for foreign currencies, and move capital out of the country. This would further weaken the currency, which—as noted earlier—would lead to further imports of inflation from abroad.

In other words, if the Riksbank wants to reach its 2% goal, it cannot lower its interest rate until the krona has stabilized against, primarily, the euro. At the same time, the market-driven erosion of the krona’s value will continue, especially since the macroeconomic variables continuously suggest that the Swedish economy is not doing well. This is in a nutshell what the Riksbank refers to when they express concerns that inflation has not yet stabilized at 2%.

Although the Swedish central bank expresses hope in being able to cut its interest rate later in 2024 and into 2025, there is a bigger threat to its ability to do so than imported inflation. This is a threat that the Riksbank is very well aware of, but out of tradition and stalwart analytical rigor will not talk about.

That threat comes from the Swedish government’s weakening budget. Its consolidated fiscal balance was negative for two of the first three quarters last year (Eurostat has yet to report on the fourth quarter). With unemployment high and trending upward, the national, regional, and local government budgets will all end up deep in the red.

This is the outlook that the Riksbank has to worry about. When the Swedish government’s need for borrowing money increases, it will do so rapidly, but it will happen with a Swedish economy that has limited opportunities to buy up that new debt. This is not a new phenomenon: historically, the Swedish government has relied significantly on foreign creditors to fund large and rapidly growing deficits.

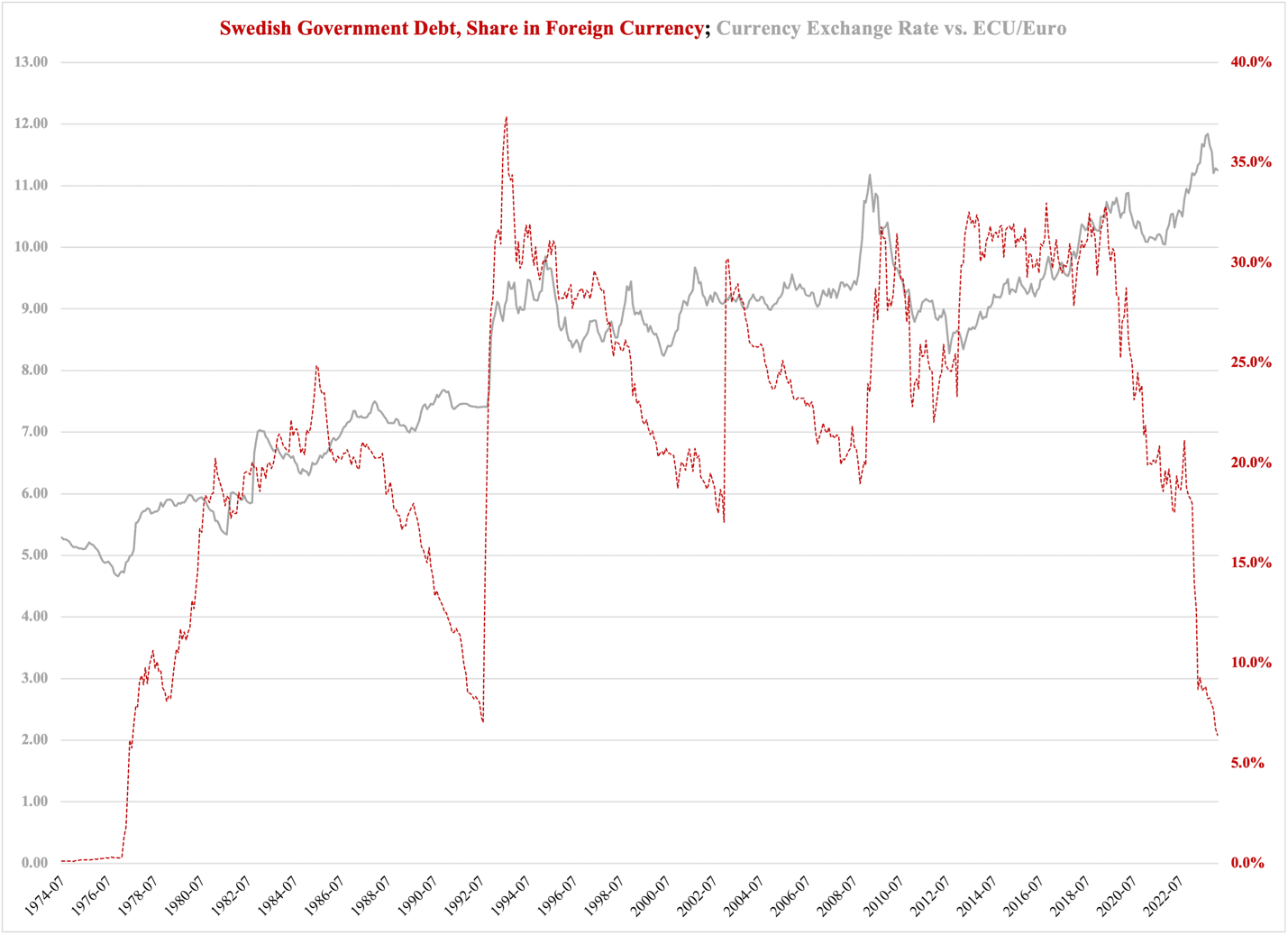

Figure 2 reports part of this history, namely that which consists of debt in foreign currency. It is reported as a share of total Swedish government debt (red) and compared to the krona’s exchange rate from Figure 1 (gray). There have been three episodes in the past where the Swedish government has borrowed in foreign currencies: the 1980s when financial markets were deregulated; the depression-level economic crisis in the early 1990s; and the 2010s.

Figure 2

Since the last peak, the Swedish government has gotten rid of most of its obligations in foreign currencies. That will change, though, when they need to rapidly increase their borrowing; unless the central bank is planning on monetizing the growing deficit, the Swedish government will inevitably need foreign creditors.

With the krona steadily weakening, it is not an attractive proposition for foreign investors to first buy kronas and then buy Swedish government debt denominated in the Swedish currency. This places the currency risk entirely on the shoulders of the investors. To counter this, the government would have to promise to pay interest rates that are of such a level, and of such a reliable nature, that those investors will find the prospect of a depreciating currency acceptable enough.

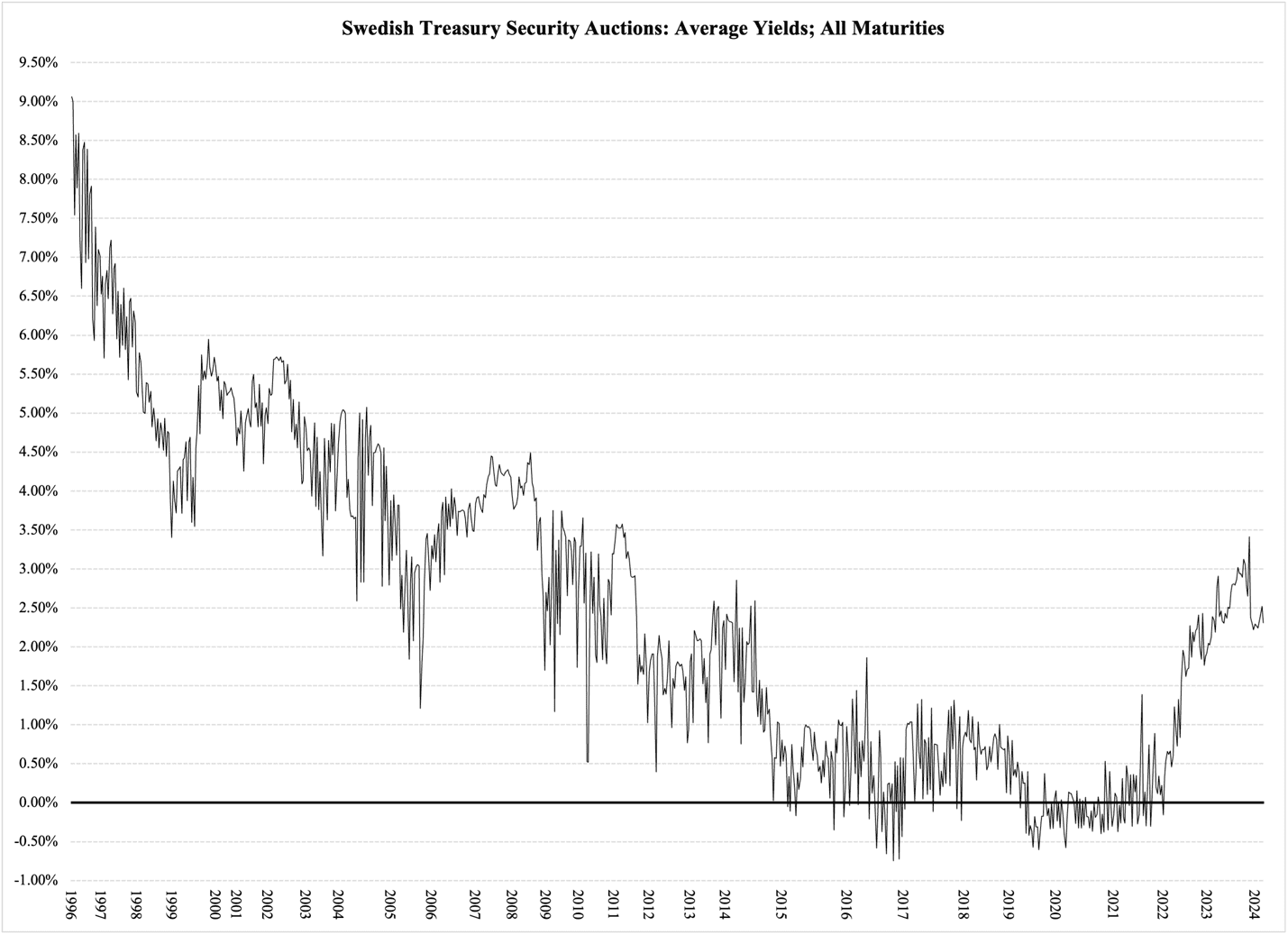

This means rising interest rates and therefore rising debt costs for the government; the interest rates that they pay today when selling new debt at auctions, will not suffice. Figure 3 reports the rates paid at the circa 25-40 annual auctions that the Swedish National Debt Office has held since July 1996:

Figure 3

Higher interest rates will be painful, both for the government and for the Swedish economy as a whole.

There seems to be no end to the erosion of the krona’s value vs. the euro. Since the government would solve the currency-risk problem if Sweden joined the euro, I would not be at all surprised if—when faced with a rapidly growing budget deficit— a large majority in the Swedish parliament agrees to simply start the euro accession process.