Donald Trump

Photo: Gints Ivuskans / Shutterstock.com

When Donald Trump recently made a speech at a campaign rally in the lead-up to the South Carolina presidential primary election, he explained that he would be tough on NATO members who do not contribute their fair share to the alliance’s combined military resources:

You didn’t pay. You’re a delinquent.

— Visegrád 24 (@visegrad24) February 11, 2024

No, I would not protect you. In fact I would encourage (Russia) to do whatever the bell they want.

You gotta pay,”

says Donald Trump, referring to countries that do not spend the NATO target of 2% of GDP on defence. pic.twitter.com/MpbLgLk1K1

In a nutshell, Trump declared that if a NATO member state does not meet its obligations, then America has no duty to fill the gap.

His statement was met with considerable pushback. Among the quickest and most vocal critics was former Congresswoman Liz Cheney:

NATO is the most successful military alliance in history. It’s essential to deterring war & defending American security. No sane American President would encourage Putin to attack our NATO allies. No honorable American leaders would excuse or endorse this. https://t.co/LhH4kA1wHC

— Liz Cheney (@Liz_Cheney) February 12, 2024

Alexander Stubb, the newly elected President of Finland, had a much more measured reaction, while other European responses were closer to Cheney’s comment. Overall, Trump’s critics ignored the former president’s two-fold point:

According to NATO’s July 2023 report on member-state military spending, only 11 of the 31 members of the alliance were expected to meet the 2% target last year. At the same time, Jens Stoltenberg, Secretary General of NATO, believes that as many as 18 states will meet that target in 2024.

The problem with the numbers for 2023 is that they are adjusted for inflation, which means that they do not accurately reflect the fiscal realities of NATO member-state budgets. Furthermore, the report does not explain how its authors arrived at the inflation-adjusted numbers: did they use a consumer-price index to adjust for inflation or the so-called GDP deflator? If they used the latter (which is likely), did they apply the general GDP deflator to defense outlays, or a defense-tailored index?

The difference can be significant, depending on how inflation in military procurement differed from inflation in general.

Another even bigger problem is that they convert defense outlays per country to U.S. dollars, and they do so based on 2015 exchange rates. This puts a major distance between reality and the numbers in the NATO report. To take one example: according to xe.com, on July 1st, 2015, $1 could purchase 2.68 Turkish liras; eight years later, that same $1 could buy 26 Turkish liras.

By using these statistical techniques, the authors of the NATO report convolute critical information on defense spending in the alliance. This makes it difficult, if not impossible, to determine whether or not all NATO members live up to their funding obligations.

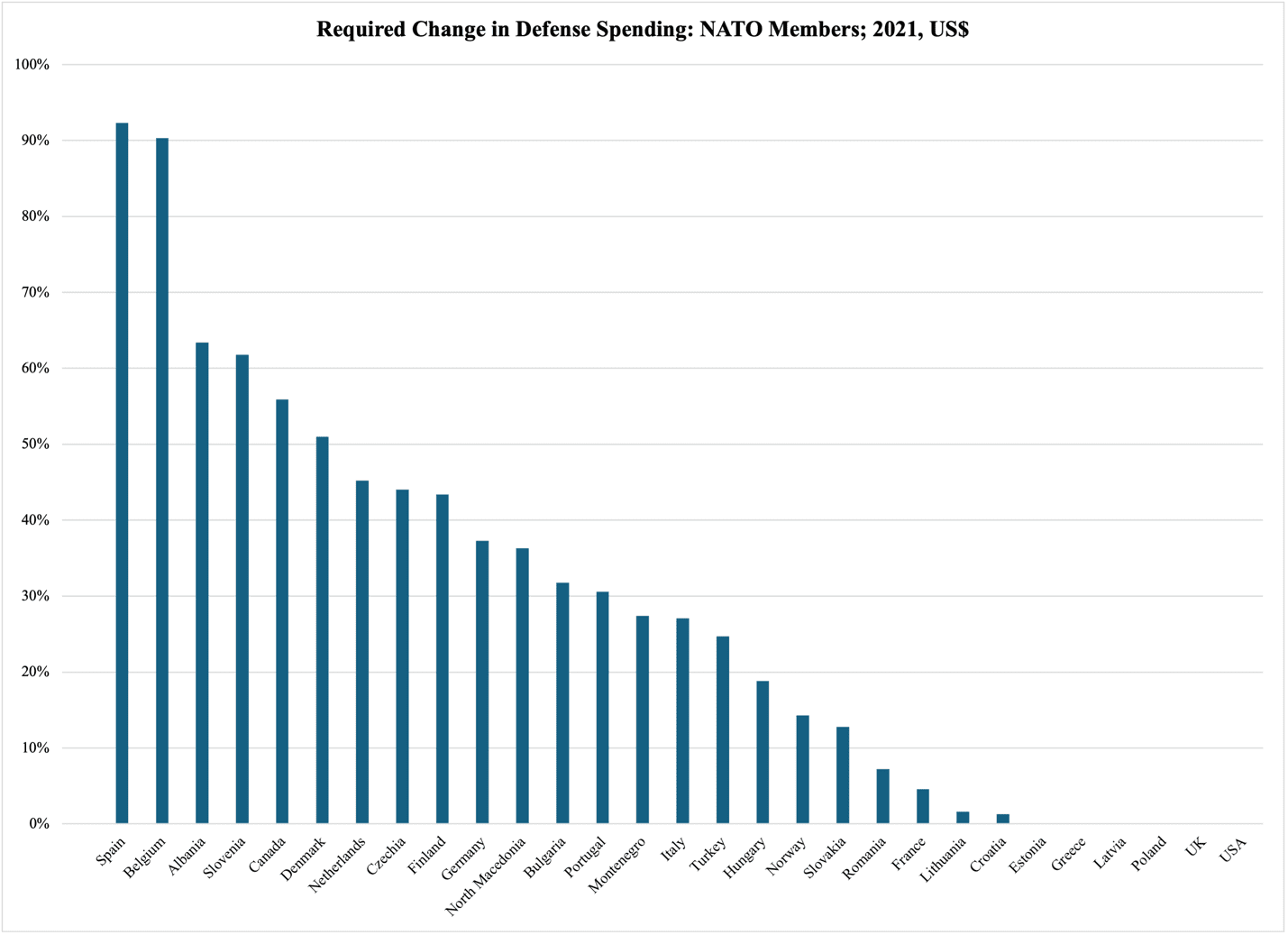

A more reasonable approach is to use current price figures for both GDP and defense spending, though all numbers should still be in U.S. dollars since that is the currency that NATO itself operates with. Approaching the 2% defense-spending target from this angle, things look a bit different than the picture we just saw. Figure 1 reports the increase in defense spending that each NATO state would have had to do in 2021 if they wanted to reach the 2% goal:

Figure 1

The year 2021 was chosen because it is the latest year for which there is reliable GDP data from all NATO member states; since neither Eurostat nor OECD regularly covers countries like Albania and North Macedonia, the go-to sources were the United Nations and their comprehensive national accounts database.

If every NATO member had met its 2% goal in 2021, the total defense outlays of the NATO members would have been almost 8% higher than they actually were. This equals just over $90 billion in extra NATO defense resources—in one year alone.

If NATO Secretary-General Stoltenberg is to be believed, the situation in 2024 is going to be vastly better than it was in 2021, although it is worth repeating that it matters a great deal what numbers the good Secretary-General relies on. However, even if he is using the ‘correct’ numbers as explained in relation to Figure 1, with 18 out of 31 member states meeting the 2% target, there is still a significant funding gap left by the fiscal slackers to be covered by someone else.

So long as such a gap remains, the question that Trump raised will remain a point of contention between America and its European defense alliance partners. It will also remain a sore spot in domestic American politics, where the federal budget is a constant source of Congressional political battles.

As I recently reported, the federal government now gets more money from loans than from any one of its taxes, which also means that any increase in defense spending will be entirely funded by borrowed money. When Trump critics like Liz Cheney argue that America must stand by its NATO allies regardless of their fiscal commitment to the defense alliance, they suggest that America should continue to borrow unlimited amounts of money for our national defense.

This view endangers further the fiscal sustainability of the U.S. government, which is already teetering on the edge of a fiscal crisis.

The idea that Congress can continue to borrow money for defense outlays does not only affect America’s relations with NATO. In an opinion piece for Fox News, retired U.S. diplomat Grant Newsham explains:

American control of the Central Pacific depends on three treaties—known as Compacts of Free Association (COFA)—with three nations: Palau, Federated States of Micronesia, and Republic of Marshall Islands. These nations and their huge maritime territory comprise most of an “east-west corridor” from Hawaii to the western edge of the Pacific that is essential for U.S. control and military operations in the region.

The continuity of the COFA, Newsham notes, depends on U.S. aid to these three countries of a total of $120 million per year. This amount is now being questioned as part of the fiscal deliberations in Congress. If the amount were to be cut, which is unlikely but not impossible, it would effectively end the COFA and, according to Newsham, open for Chinese expansion in the region.

There is only one reason why the COFA funding would be gutted: Congress is put in a situation of fiscal panic where it is forced by global sovereign debt investors to make the biggest possible spending cuts and tax hikes within the shortest possible period of time. In some ways, this sentiment has already worked its way into the appropriations process in Congress, although it remains limited to the most fiscally hawkish faction of the Republican party.

However, regardless of how the COFA and NATO funding issues are resolved, the tensions over both illustrate with chilling clarity how the U.S. government’s decades-long fiscal irresponsibility has now become a clear and present threat to America’s national security. Anyone proposing more spending with borrowed money should consider what happens when the increasingly uneasy debt market has had enough of U.S. debt.