It may seem like a small technicality, but this is actually an important piece of news: right around New Year, the yields on U.S. debt securities stopped falling and started creeping upward.

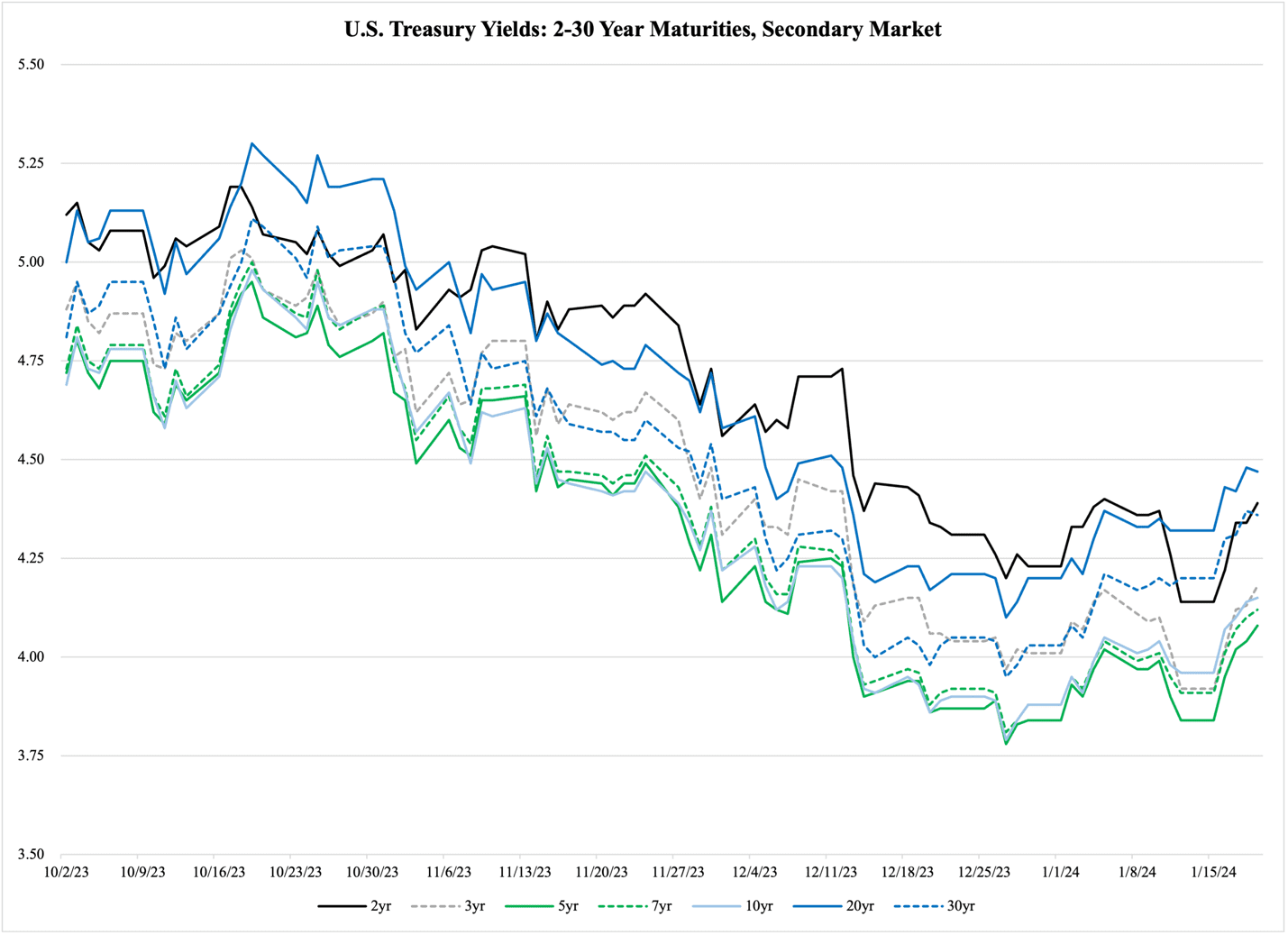

The trend has been modest and—as is usual for the bond market—a bit jumpy. However, in the last week, all the yields on longer securities, maturing in 2-30 years, jumped noticeably. Figure 1 reports daily yields in the secondary market, i.e., the market where those who already own debt securities can sell them:

Figure 1

There is no apparent explanation for this uptick in yields. Inflation in consumer prices, which was a driving force behind the recent rise in bond yields, has fallen to a level in the vicinity of 3.2-3.3%. Although it can appear to have gotten stuck at that level, there is nothing dramatic about that. Producer prices are still pulling consumer-price inflation downward.

Another important variable, overall economic activity, or GDP, also points toward lower yields. Recently, the Federal Reserve voiced recessionary concerns and pointed to December as a relatively modest month for the economy. The Fed’s report hinted at an imminent recession, which in turn means we can expect higher demand for Treasury securities. When banks sell fewer loans due to an economic slowdown, they park excess liquidity in government debt. This increases demand for that debt, which lowers yields.

Expectations of rising demand for Treasury securities should push current yields down, not up, as speculators try to capitalize on the coming price hikes. We are currently witnessing the very opposite.

The new trend of rising yields is not yet visible in shorter-term securities that mature in one month to one year. Yields on six-month and one-year bills have just turned upward, but the uptick is later here than for longer maturities.

What is the reason for this rise in yields on U.S. government debt? Before we look for an answer, let us examine the primary market for U.S. debt, namely the auction market where the Treasury sells new debt.

Auctions are for the most part held on weekdays, except Fridays, with maturities from one month through six months being auctioned weekly while those that mature in one year all the way up to 30 years are sold at monthly auctions.

There are tendencies to rising yields across the maturity spectrum, but it is not universal. Starting at the shorter end, the yield on the four-week Treasury bill has not yet started rising. After topping at 5.305% on October 12th last year, it fell at a creeping pace and reached 5.255% on January 11th. At its latest auction on January 18th, it paid 5.250%.

In other words, its yield decline has slowed down. The secondary market yield for the four-week bill has remained steady at around 5.54% since the New Year.

The eight-week bill, which is a ‘twin’ security to the four-weeker, saw an uptick in the yield at the latest auction: on January 11th it sold at 5.250%, with the January 18th auction landing at 5.255%. The same thing happened with the 17-week bill: on January 10th it was auctioned at a yield of 5.155%; on January 17th it sold at 5.170%.

Another notable jump came at the January 22nd auction of the 6-month bill. The Treasury had to pay 4.99% to sell the debt it needed to sell at that auction. This was an increase from 4.95% the week before.

As for longer-term securities, the Treasury’s auction of new 20-year bonds on January 17th ended with a yield of 4.36%. This was a notable rise from 4.147% on December 20th.

In November, this very same auction resulted in a yield of 4.73%—which makes both the December and the January yields quite spectacular. It is worth noting that the volume of debt was the same in December and January: $13 billion, and only marginally higher at $16.2 billion in November.

In other words, the yield increase at the January auction had nothing to do with the Treasury trying to sell a remarkably larger volume of debt.

This point is applicable generally: it is not the case that the Treasury has suddenly started pushing dramatically higher volumes of debt into the market. If it had, this would be an obvious explanation for why yields are rising.

A more plausible explanation of the end to the falling debt yields is that investors are paying attention to the fact that Congress is chronically, perennially, and catastrophically unable to unite around spending restraint. Currently, the lawmakers on Capitol Hill are barely able to keep the authorization of federal spending going for a few weeks at a time.

There was a time when Congress fulfilled its constitutional obligation and passed a budget each year. It is easy for the independent observer to get the impression that those days are permanently behind us, but even if there are members of the legislature who are trying to work their way back to annual, orderly appropriations, the overall impression is that they are fighting an uphill battle.

The consequence of this is that the debt continues to rise. As I reported recently, new debt is now the biggest revenue source for the federal government. If I were an investor with a portfolio of U.S. Treasury securities and I witnessed this, I would ask myself just how much of this government’s debt I want to own.

It is likely that some investors have started asking themselves this very question. If this is indeed the case, we will see a slow rise in yields both on the secondary market and at auctions in the near future. Watch out for the Treasury’s auctions this week of the two-, five-, and seven-year maturities.