April is a good month to be a tax collector in America. The federal government is awash in tax payments from individuals and businesses who want to catch up before the April 15th tax filing deadline. So much money is flowing into the U.S. Treasury that the government debt has dropped by $28 billion since April 1st.

In one short week, tax-paying Americans have done more for the fiscal sanity of their government than Congress has done in 25 years.

Unfortunately, the past few days’ worth of good fiscal news is an exception—a predictable one, but still an exception. As soon as the tax filing season is over, the debt will start growing again. Everybody knows this, especially investors in U.S. government debt, who are not impressed with a temporary spike in tax revenue.

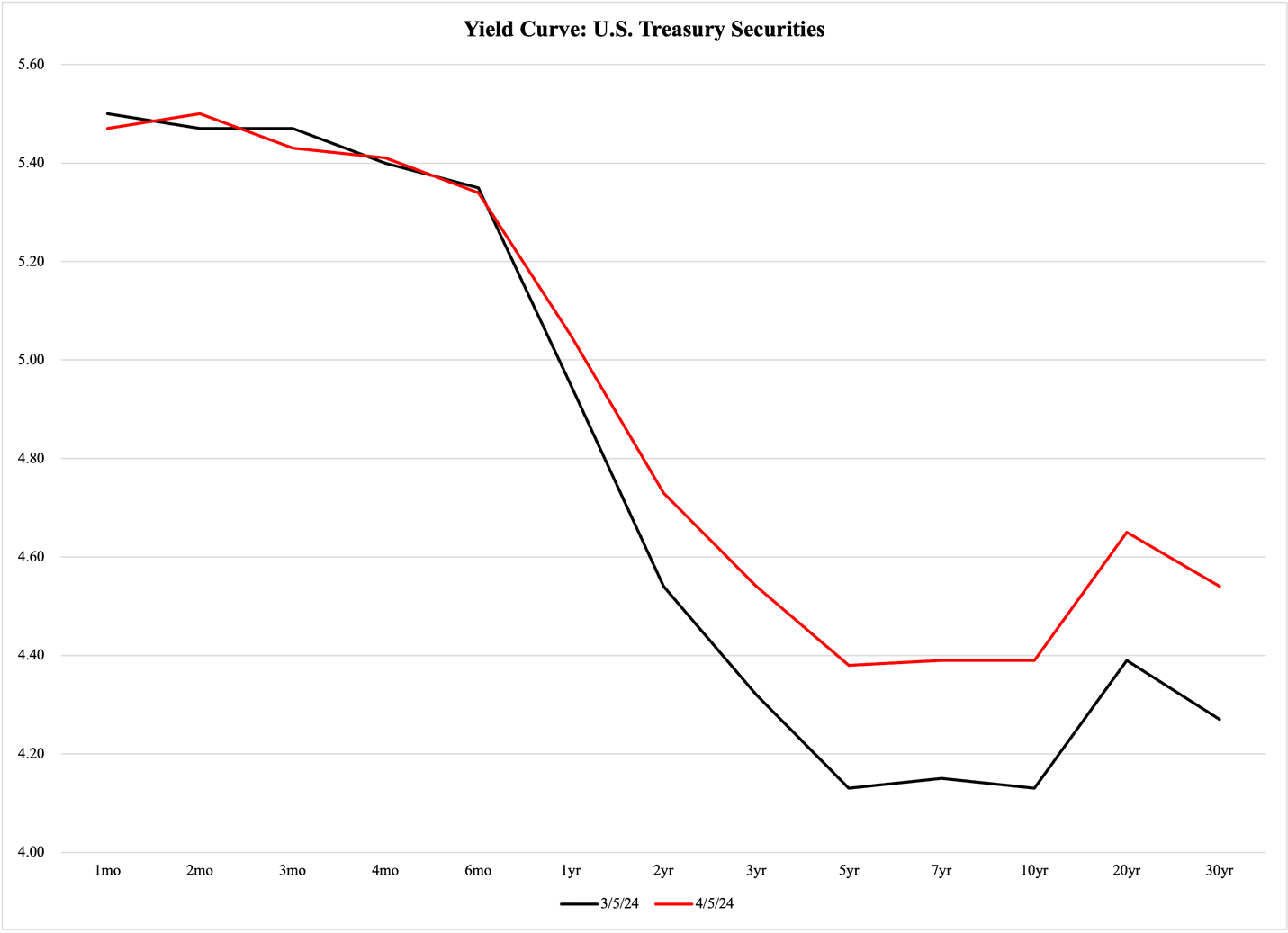

We see this first and foremost in the interest rates in the secondary market for U.S. debt. These rates have risen quite a bit in the last month, especially on longer maturities. Figure 1 reports the traditional yield curve, i.e., the curve that illustrates the different yields, or interest rates, on the maturity classes of sovereign debt (in this case U.S. Treasury debt). A comparison between the yield curves from March 5th and April 5th tells the story well:

Figure 1

Back on March 5th, not a single maturity from two years and up paid more than 4% in yield; on April 5th, every maturity from two years and up paid more than 4%. The rise in rates in this segment of Treasury securities was strong enough to pull up the unweighted average yield for all maturities from 4.77% to 4.91%.

The increases in yields on long-term debt would be unproblematic if they were coupled with corresponding declines in the yields on shorter-term debt. That is not happening, though; the increase in long-maturity yields has been followed by a sustained pressure on short-maturity yields.

The most prominent example of this pressure is found under the shortest of all maturities, namely the 4-week Treasury bill. Under a policy shift announced in January, the U.S. Treasury has gradually been shifting the issuance of new debt to longer-term maturities. As part of this policy, it has reduced the amount of debt auctioned under the 4-week bill. After having auctioned on average $89.5 billion in debt every week since the start of the 2024 fiscal year on October 1st, the two most recent auctions (March 28th and April 4th) sold, respectively, $75 billion and $70 billion.

Alongside the 4-week bill, the Treasury also sells its 8-weeker, which has gone through a similar reduction. After a steady average of $84 billion per week, the Treasury has cut it in two steps to $80 billion and $75 billion.

While the Treasury offers a smaller amount of debt under these two maturities, demand for that debt has remained the same or even ticked up a bit. On April 4th, when the 4-week auction sold $70.3 billion in debt, investors offered to buy $219.6 billion, which makes for a so-called tender-accept (T/A) ratio of 3.1, or $3.10 in offers per $1 of debt sold. The T/A ratio for this bill has not been this high since August.

With demand high, the mechanics of the debt market dictate that the interest rate should fall. That has not happened, though: the yield that the Treasury had to promise to pay at the April 4th auction, 5.23%, was marginally lower than the 5.26% paid at the last 25 auctions. The 8-week auction of the same day paid 5.25%, almost indistinguishable from the 5.27% 25-auction average.

The most recent auctions of 13-, 17-, and 26-week bills follow the same pattern, which suggests that the gradual reduction of debt sold under short-term maturities is not reassuring investors. While there are marginal downward adjustments in auction rates, they are so small that it is impossible to distinguish them from regular market fluctuations. This means that the U.S. Treasury is still generally reliable in the eyes of debt-market investors, but that the reliability margins are wearing thin.

If those margins were thick, the Treasury would see a significant response from the debt market in the form of lower interest rates. As things are now, a cut in the sale of new debt results in a ho-hum response from investors, as if the decline in sales of short-term debt sends investors looking for other opportunities, not the same opportunity—U.S. Treasury debt—but with different maturities.

The mirror image of this lukewarm investor attitude is the rise in interest rates on long-term debt. This increase has first and foremost happened in the secondary market, not at the auctions, but it is likely that we will see the same happen at the auctions of 3-, 7-, and 10-year Treasury notes this week. Those rate hikes would solidify the impression that investors are starting to look away from short-term U.S. debt but not becoming more interested in its long-term maturity classes.

All in all, the market for U.S. sovereign debt suggests that the Treasury is struggling to convince investors of how good it is to buy its debt. This struggle has not yet taken the toll on the U.S. economy that it potentially can do; the average interest rate on the federal government’s debt—which is currently stable around 3.15% and even ticked down a notch last week—is likely to rise and pull other interest rates with it.

One of the many consequences of rising interest rates on U.S. debt is that the Federal Reserve comes under pressure from the debt market not to cut its federal funds rate. This could make the Fed’s situation even more difficult than it already is, especially since there is unrelenting pressure on them from the political Left to cut rates.

The U.S. economy is doing well, but the slowly growing uneasiness on the market for federal government debt could easily grow into a problem big enough to derail it.