In a story on the British Labour government’s first budget, Deutsche Welle explains that Prime Minister Starmer and his party have been forced to make very tough fiscal decisions. The reason, according to DW, is that they

inherited a sluggish and indebted economy after a decade and a half in opposition to the Conservative party

For this reason, DW suggests, the Labour government has had to present “a tough budget” constrained by a deficit of £22 billion.

This German news outlet allows itself a large degree of creativity in its approach to the facts behind this new British government budget. As we will see in a moment, the many years of government in the hands of the Conservatives have actually led to some improvements in an otherwise lackadaisical British economy.

Before we examine the factual errors in the DW story, let us take a brief look at what the Starmer government is doing to—in its view—address the fiscal reality in which they find themselves. On the one hand, they are trying to get harsh spending cuts done; DW again:

While the decision to introduce a means test for the winter-fuel payment would cut the number of people receiving it from 11.4 million to 1.5 million, saving well over 1 billion pounds in the process, it left the government open to accusations of austerity.

On the other hand, Prime Minister Starmer is in favor of widespread tax hikes:

Keir Starmer said recently that the country must face the “harsh light of reality,” and up to 35 billion pounds is expected in tax increased when [Chancellor of the Exchequer] Reeves announces the details of the budget to the House of Commons

Predictably, Deutsche Welle tries to stir up some controversy around the term “austerity” with reference to earlier statements by Labour politicians. However, the real question here is not to what extent the Labour Party has promised to cut spending and raise taxes in the past; the real question is what their combination of austerity measures would do to the British economy—and whether or not they are at all necessary.

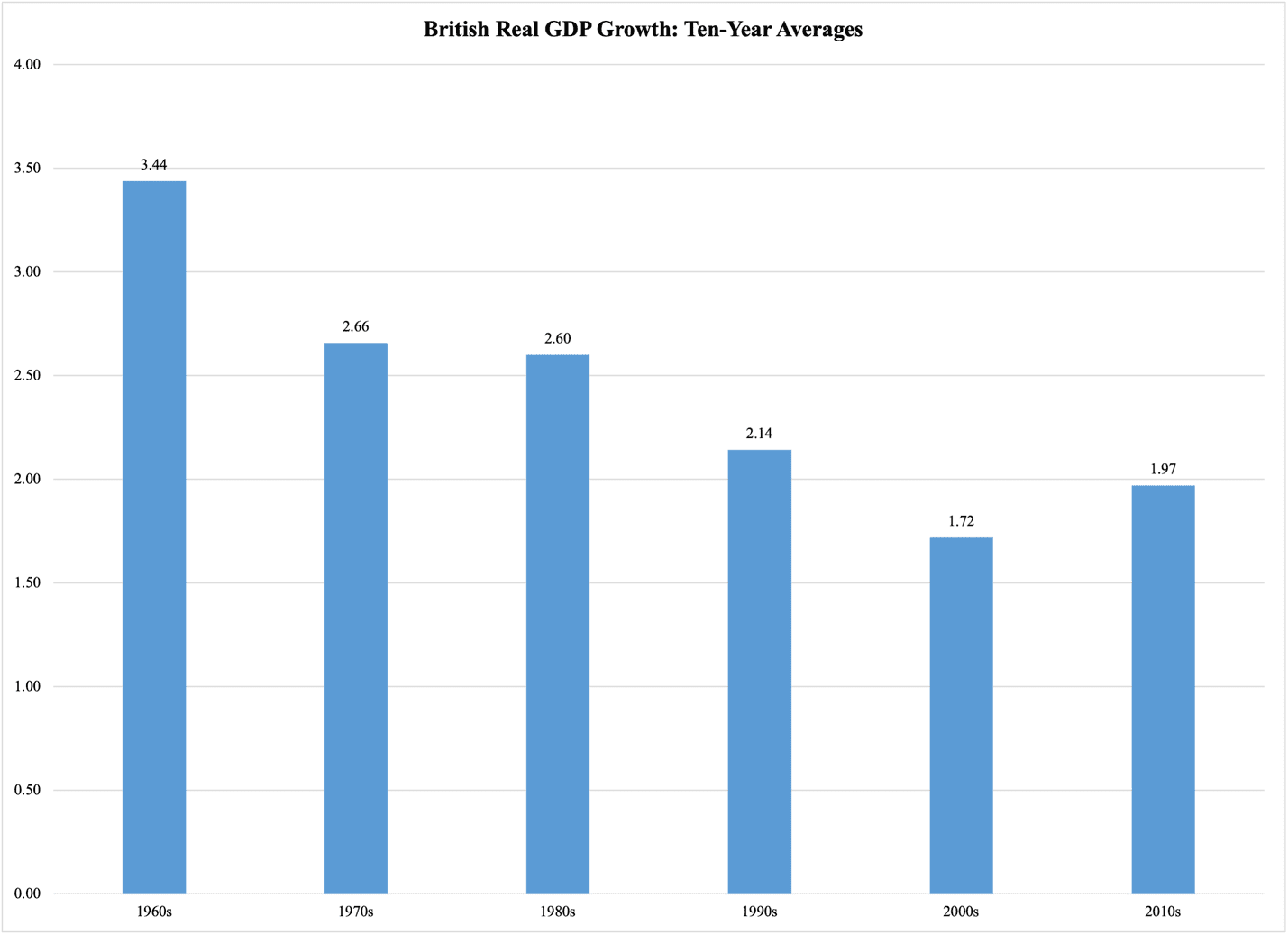

To answer these questions, we need to bring in the earlier statements by DW, where they blame previous conservative governments for fiscal and even macroeconomic mismanagement. Put plainly, Britain has not suffered from either type of mismanagement, especially not of the kind alluded to by Deutsche Welle. To begin at the highest macroeconomic level, it is correct that the British gross domestic product, GDP, has been growing sluggishly under the recent Conservative governments, but that has very little to do with their policies. It is instead part of a long-term trend where Britain, like almost all of Europe, has drifted into a state of long-term economic stagnation.

Figure 1 reports the average inflation-adjusted growth rate in GDP by decade. The period 1960-1969 is the only one (in recent British economic history) where the economy has averaged more than 3% real growth per year; more striking—from a negative viewpoint—is the fact that since the turn of the millennium, the country has been stuck in a long-term path well below 2% real growth:

Figure 1

The slow but seemingly unstoppable decline in economic growth has the nasty consequence of also slowing down the growth in tax revenue. At the same time, the spending side of the government budget is full of programs that provide social benefits to people. The spending on these programs is not determined by the annual GDP growth rate, but by the growth in the eligible population.

If eligibility criteria are de facto or de jure inflation-indexed, spending will automatically grow faster than tax revenue. If, on top of that, many of the benefits are means-tested, the imbalance in the budget is bound to grow even faster. The reason is the slow GDP growth: with a virtually stagnant economy, more and more people are trapped in jobs with low and stagnant pay, which—due in part to inflation indexing of spending—pushes more people down into eligibility for means-tested benefits.

The budget shortfall that emerges from this process is referred to as a ‘structural budget deficit.’ It is built into the very structure of modern welfare states—and Britain is no exception.

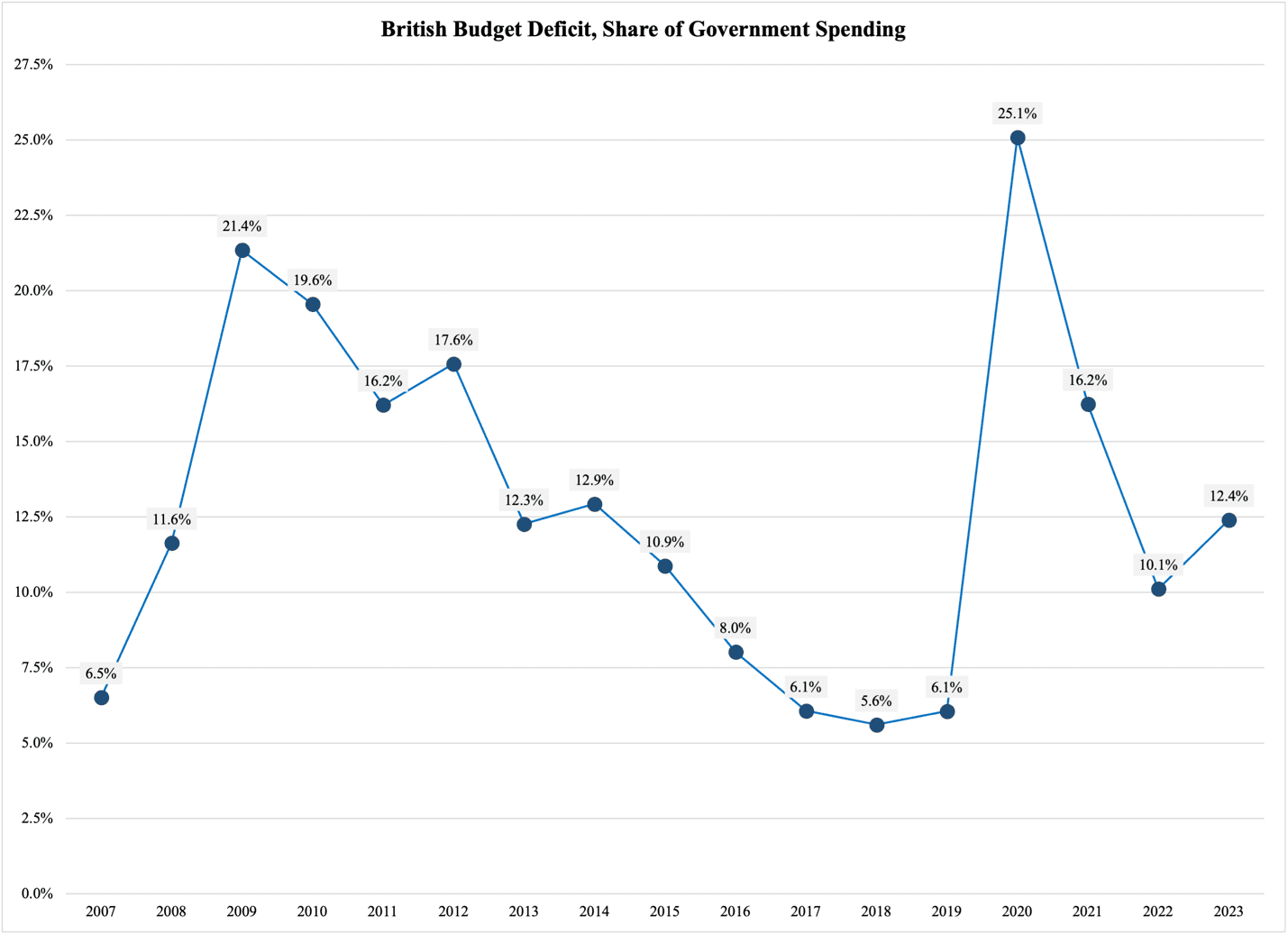

With this in mind, it is frankly remarkable that, in the past 10-15 years, the British government has been able to rein in its deficit and essentially bring its deficit growth to a halt. Figure 2 reports the annual deficits in Britain’s consolidated government finances; the number reported is the budget deficit as a percent of total government spending:

Figure 2

It is not surprising that the Conservatives never managed to eradicate the budget deficit—for that to happen, the British economy would have had to grow by well over 2% per year. However, they did bring the deficit down as a share of government spending: after the top at 21.4% in 2010 under Gordon Brown’s Labour government, conservative prime ministers David Cameron and Theresa May led the efforts to bring that deficit down to the 5.6-6.1% neighborhood by 2017-2019.

The problem for the Conservatives began with the pandemic. Prime ministers Boris Johnson, Liz Truss, and Rishi Sunak were not able to rein in the deficit as their predecessors did. Last year, the deficit-to-spending ratio exceeded 12%, setting the British government’s finances back ten years.

With that said, though, the main message in Figure 2 is that the Conservatives did indeed do a fine job managing British public finances; prudence and patience may not have been their motto, but the result of their work makes it look as if that were the case.

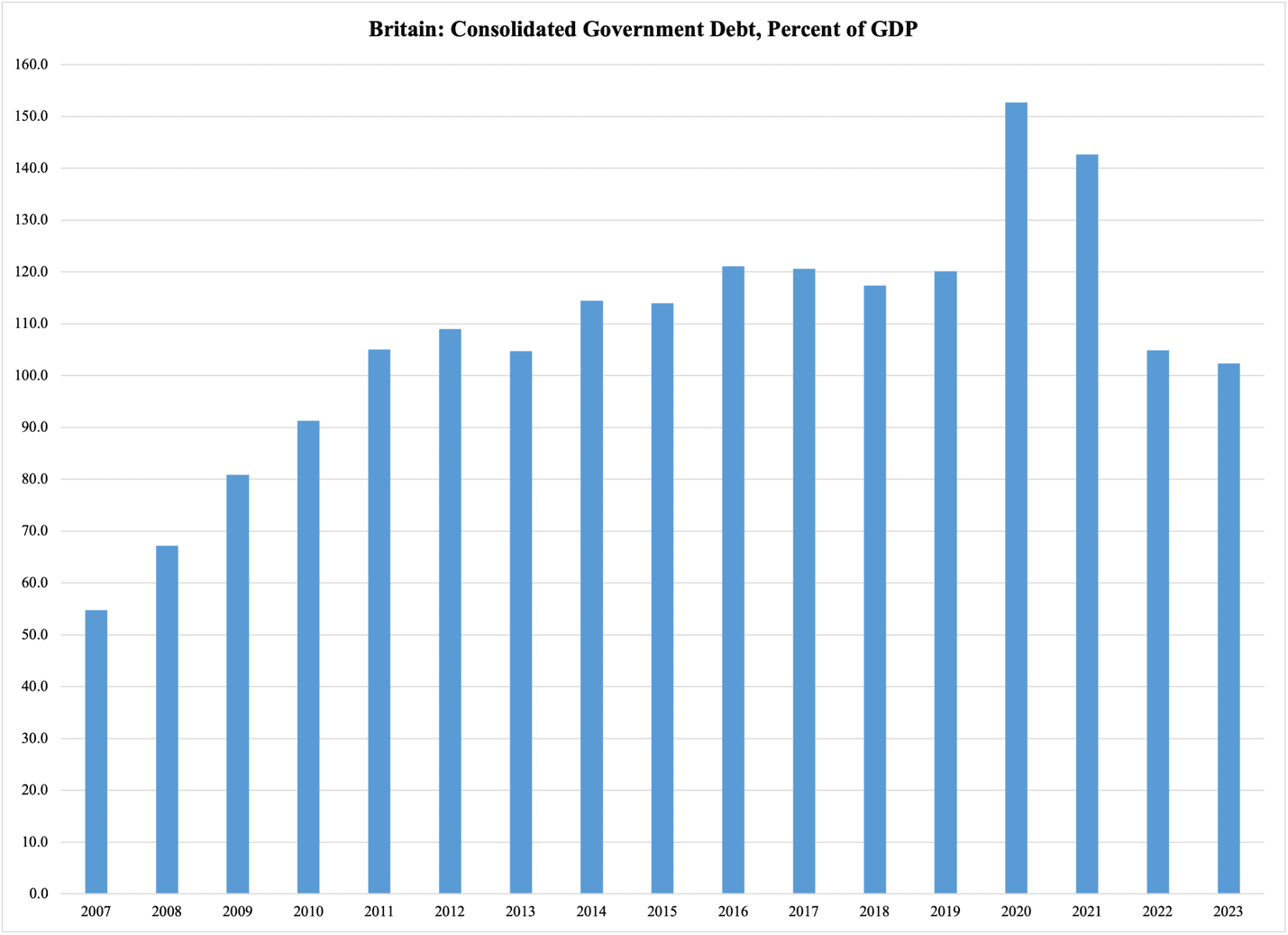

As a result of the slowly declining deficit, the Conservative governments of the last decade were able to stop the rise in the ratio of government debt to GDP. Figure 3 reports this ratio since 2007:

Figure 3

The fact that the debt-to-GDP ratio actually fell after the pandemic years of 2020 and 2021 is attributable to a temporary growth spurt—in short, a statistical anomaly. Nevertheless, the main message, again, is that the Conservative Cameron and May governments brought the growth of the government debt to a halt.

It would be correct here to point out that they did not end the growth of the debt in nominal terms, but that figure is in itself of no particular meaning. The debt-to-GDP ratio is considerably more important, since the ability of the economy to pay for the debt costs hinges critically on the real growth in GDP. So long as it grows at least on par with the debt, the government has a fair chance to continuously honor its debt obligations.

All in all, the Conservatives did a commendable job of managing Britain’s government finances, especially under the adverse condition of a GDP that, adjusted for inflation, grew by less than 2% per year.

There is a way to bring Britain out of its structural stagnation. However, that will not happen until the Conservatives open themselves to new economic visions. In the meantime, the big question now is whether Labour’s Keir Starmer will be able to bring the British economy back to growth. Although his first budget aims to borrow money for public investments, I am inclined to say no. The reason is simple: with his planned austerity measures, he wants to suppress today’s economic activity in the hope that debt-funded investments will stimulate more of it tomorrow.

However, by suppressing the aggregated purchasing power of British households through massive tax hikes, Starmer will set in motion an austerity-driven negative multiplier in the economy. By lowering economic activity today, the Starmer government erodes the fiscal and macroeconomic payoff on the investments it makes for tomorrow.

So long as the higher taxes remain in place, there will be no recovery in current economic activity. This cancels out—and probably dwarfs—the positive future accelerator effects of the investments. As a result, the Starmer government will be left with a larger budget deficit—and an even more depressed economy than when he got into office.