The U.S. government has a debt of $31.5 trillion. This is equal to almost 130% of the country’s gross domestic product, GDP. The federal budget deficit in 2022 exceeded $1 trillion and is widely expected to remain at that level for the foreseeable future.

With this much debt, and with a trend of unending growth, it is almost self-evident that America is bound for a fiscal crisis. Yet this concept is almost unknown to the political leadership in Washington. Their attitude—judging from my own experience and from what current insiders relay—is that America somehow is immune to the kind of loss of credit worthiness that has sent many other countries into a fiscal tailspin.

This is a dangerous attitude which can only be changed with relentless information—or with a real fiscal crisis.

Hoping for the former to prevent the latter, we need an all-hands-on-deck attitude to educating the lawmakers and their staffers on Capitol Hill. However, those are not the only ones who need to understand the true threat of a federal fiscal meltdown: the political leaders of all the 50 states will also be faced with major problems of a kind they have not dealt with before.

Most Americans do not know how dependent their states and their local governments are on the federal government. To make matters worse, in my experience, many state legislators are also ignorant of the intricate and substantial fiscal ties between Washington and the 50 states. Those who do understand how much of their state government’s revenue comes from the federal government often convince themselves that nothing will ever happen to those federal funds.

They are wrong. Fiscal judgment day will come, and when it does, Congress will have to make panic-driven spending cuts. These cuts will put every spending program on the chopping block in the hunt for the biggest possible spending reductions in the shortest possible amount of time. Every year the federal government sends more than $1 trillion to the states and to local governments; with a budget of $6.4 trillion, it is impossible to make real, substantial cuts without also reducing the funds going to the states.

It is not hard at all to find information on the fiscal entanglements between the federal government and the states. The National Association of State Budget Officers publishes a detailed, annual State Expenditure Report, and the Census Bureau provides detailed data over state and local government spending. Together, these sources tell a grim picture of how exposed the states are to a federal fiscal crisis.

Of the $1,085 billion that the states got in 2022, $540.1 billion went to Medicaid. This is a health insurance program primarily for families with low incomes (most Americans still rely on private insurance plans), but it also pays for a substantial part of long-term care for the elderly. States are responsible for running Medicaid and, as part of their obligations, they have historically contributed about half of the total funds that go into Medicaid. However, the federal share took a leap upward with the 2020 pandemic: since 2021 the federal government pays for 68% of all Medicaid costs in the country.

The share varies from state to state, from less than 49% in Connecticut to 84% in Arkansas, New Mexico, and West Virginia. However, no state would escape significant budget cuts if the federal government had to deal with a fiscal crisis. As little as a 10% cut in the federal funds for Medicaid would leave state lawmakers in a serious predicament. They are responsible before their state’s Medicaid enrollees for keeping the program up to shape and in compliance with federal regulations—yet, if the federal government yanks part of the money they provide, the state legislators and the governor are the ones who will have to explain health care cuts to their residents.

Either that, or raise taxes on their constituents in order to compensate for the federal cuts. Neither option is palatable to the people who are elected to run the states, but they both protect Congress and the president from the wrath of the electorate.

Federal funds play a smaller role in education funding, with $120.4 billion in 2022. On average, they fund 22.4% of state government spending on elementary and secondary education, or what Americans refer to as K-12 schools. The share shrinks when we take the outlays by local governments into account (school districts count as independent local government entities), but the political fallout from federal spending cuts would likely be just as serious as with cuts to Medicaid.

Congress also sends money to the states for a host of other programs: in 2022, they paid out $55.8 billion for transportation, which primarily means highways; $37.6 billion for states to run colleges and universities; $20.6 billion for social welfare programs; and a bit over $310 billion for other purposes. In other words, the federal government is deeply involved in states’ finances.

However, their fiscal tentacles do not stop there.

In 2019 they paid out $70 billion directly to local governments. This accounted for only 3.4% of total spending at the local level, but it was still a substantial increase from only a few years before, when federal funds paid directly to cities, counties, and school districts were almost unheard of. The tradition has been that federal money would always go to the states, which would then decide whether or not to pass any of it on to local governments.

Federal funds always come with strings attached, in the form of regulations that dictate how states and local authorities are allowed to run the federally funded operations. It does not matter how large or how small the federal share of the budget happens to be—as soon as federal money ‘touches’ an activity, that activity is subject to all the rules that the pertinent federal agency sets up.

In the case of education, federal funding is increasingly being tied to so-called Title IX regulations. Last summer, the Biden administration moved to tie school-lunch funds to how well school districts complied with Title IX. Specifically, schools would have to allow boys who identify as girls to change in girls’ locker rooms in order not to jeopardize the money that subsidizes school lunches for kids from poor families.

The ideologization of federal funds is a problem for states and local governments, but it is obviously separate from the dangers that come with a federal fiscal crisis. However, it shows that the current president and his administration are willing to unabashedly inject ideological preferences into the disbursement of federal funds, which means that in times of a fiscal crisis, they could choose to cut funding based on the very same criteria. A state like Florida, which is generally opposed to the sexualization of children’s learning in schools, could be treated more harshly than a state like California, which kowtows to the radical leftist president everywhere he goes.

Constitutionally, it is Congress and specifically the House of Representatives that is responsible for the federal budget. They could deprive the president of the ability to use ideology in coming budget cuts, but in order to do so, they would have to bring the Senate along as well as convince the president not to veto their budget. As things are currently, Congress has delegated considerable authority to the president, allowing him and his administration to use regulatory power where legislation once reigned unchallenged.

In times of fiscal stringency, this delegation of powers would likely become a problem in the relations between Capitol Hill and the White House, and it would not be limited to education funding. The federal government funds roughly 25% of state transportation budgets; if cuts were to be made, the Biden administration could conceivably agree to make the cuts, provided that Congress did not make any specific demands regarding how those cuts were executed. This would leave the president and his Department of Transportation to, e.g., prioritize funding for charging stations for electric vehicles, and instead let all the budget cuts fall on states that do not go far enough in banning cars with internal combustion engines.

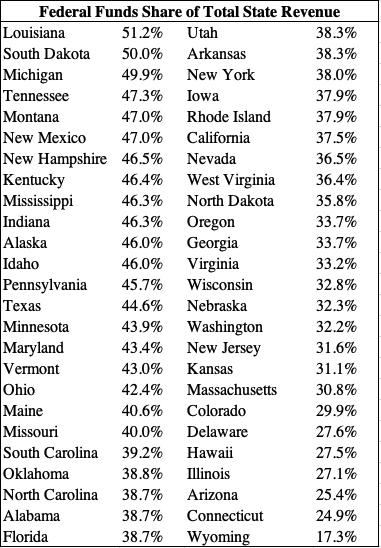

As mentioned, the share of federal funds in state budgets varies from state to state. As of 2022, these were the federal-funds shares of state budgets:

Table 1

Source of raw data: National Association of State Budget Officers

These numbers are very high by historic comparison. In the first decade of the 2000s, it was close to impossible to find a state where federal funds paid more than 40 cents of every dollar the state spent. Those days are gone, one reason being the expansion of Medicaid in the last few years. Another reason is the growing ambition of the federal government to involve itself in children’s education, a policy area that historically has been stalwartly protected by local governments and states.

Not only does the growth in federal funds make states vulnerable to a fiscal crisis at the federal level, but when those funds account for more than half of all the money a state spends, it is fair to ask whether or not that state is still effectively an independent entity. The United States constitution unequivocally defines the states as sovereign jurisdictions, and the federal government as a residual power (primarily per the 9th and 10th Amendments to the Constitution). State governors and lawmakers are quick to talk about their independence, and about how they don’t listen to ‘Washington’—yet their desire to accept a seemingly unlimited amount of funding from that same ‘Washington’ really calls into question to what extent they actually understand what it means to be an independent jurisdiction.

The political leaders of America’s 50 states today are more dependent on the federal government than any generation of leaders before them. When a fiscal crisis hits the American economy and the federal government is forced to make rapid, and drastic spending cuts, the reaction in the state capitals could be one of accelerated fiscal panic.

There is only one way the states can reduce that risk: by starting reforms to reduce their dependence on federal funds. It is not an easy thing to do, but if it were easy, someone would have done it already.