After months of saying that he would never negotiate the debt limit or debt ceiling with the Republican majority in the House of Representatives, President Biden finally agreed to a meeting. The purpose was to find some way for the president and, primarily, his political opponents in the House, to agree on how much money the federal government should be allowed to borrow in the near future.

The debt ceiling is a statutory limit on how much money the federal government is allowed to borrow. Currently, Congress has run out its credit line; the federal government is at the moment resorting to extraordinary measures to make sure it can finance its outlays. In general, fiscal bean counters in Washington agree that, come June 1st, those extraordinary measures will be exhausted.

Democrats and Republicans in Congress have been deadlocked over the debt ceiling for months. There has been a lot of drama around the impasse, with some claiming that the U.S. government is going to “default” if there is no agreement by June 1.

I hate to disappoint the drama merchants, but there will be no such default now—as boring as it sounds, the U.S. government is going to be able to pay its bills in June. Congress and President Biden will reach an agreement.

Under normal circumstances, I would immediately assume that they will only construct another stopgap measure. If history were the only guide we had, Congress and President Biden would fail to address the structural deficit that is the root cause of all the excessive borrowing.

There is a case to be made for history to guide our outlook on the debt ceiling issue. According to the White House’s Office of Management and Budget, the U.S. government has operated under a debt ceiling since 1940. Congress has modified the statutory ceiling well over 100 times. It has rarely caused any controversies, not even on the occasions when Congress has simply suspended the limit (most recently from August 2019 to October 2021).

Since old habits die hard, it would be fair to assume that we will see a similar outcome this time. However, history has lost some of its influence on current events. The members of the Republican majority in the House are more fiscally conservative than they have been since Eisenhower was president. They will demand a hefty price from the Democrats in order to accept a deal on the debt ceiling. In fact, there is a sizable minority among them who, if faced with the choice between defaulting the U.S. government or simply raising the debt ceiling, will choose the former without hesitation. They would see it as a measure to force their less fiscally conservative colleagues into a conversation about spending cuts.

It is difficult to get official commitments to such a hard line, simply because it raises tensions within the Republican House caucus. However, they have already shown their clout by forcing Kevin McCarthy, the Speaker of the House, to hold firm on the debt ceiling issue, and they did so in a politically clever way. In order to let the federal government borrow more money, House Republicans have passed a bill that allows Congress to increase the federal government’s debt limit by $1.5 trillion through March next year. In return for that increase, they want a cap on how much so-called discretionary spending can increase per year. That cap, they say, has to be capped at 1% per year.

This is not quite as good as it sounds. Discretionary spending currently accounts for about one-third of total federal spending. It is supposedly easier to put spending restrictions on those programs instead of mandatory spending, i.e., those that are regulated by law, which in Congressional parlance applies primarily to Social Security and Medicare.

From a fiscal viewpoint, the distinction between discretionary and mandatory spending is entirely artificial. A program that provides benefits of some kind is mandatory in the sense that those who receive the benefits have been promised that they will receive them on an ongoing basis. In other words, when we look at government spending, a promise by government does not have to be written into law to be mandatory.

House Republicans ignore this point and instead limit their spending cap to the discretionary one-third of the federal budget. At the same time, the very fact that they propose a cap, as well as ideas for structural spending reforms, is a major step forward. It is an advancement even if we compare it with what Republicans have suggested in the past; the 1% spending-growth cap is a nice twist on the so-called ‘penny plan’ that Senator Rand Paul has been touting for many years. However, unlike the senator’s idea, which would cut spending by 1% per year, the new plan caps spending growth to one penny per dollar spent.

As mentioned, if we relied solely on historic experience, there would be no reason to expect Democrats to agree to any structural spending reforms. However, the situation has changed, in part because House Republicans were smart enough to pass a bill that allows for an increase in the debt ceiling by $1.5 trillion. So far, Democrats have done nothing to match this initiative; if they continue in the same fashion, they end up in the awkward position of making government run out of money.

They will not let that happen. Democrats have already taken steps to move the House debt-ceiling bill forward in the Senate. They have done so in a manner to speed up its processing; the big question is what Democrats will give Republicans in exchange for a raised and extended debt ceiling.

It is difficult to say at the moment what the Democrats are willing to give. What is practically certain, though, is that it will not be concessions on structural spending. The Democrats would never lend themselves to reforms that reduce the government’s formal benefits promises.

Here is where it gets interesting. They could very well agree to limits on spending that are said to be temporary in nature, or otherwise look like an exception to the rule. It would be a political stunt for them, a chance to blame Republicans for having forced the spending restrictions on the American people.

In other words, formidable rhetoric to the general public, and quiet bipartisanship behind closed doors. If this turns out to be the solution, it gives us some insight into how Congress would handle a full-blown fiscal crisis, once they encounter one. While keeping the shell of the welfare state intact, they would hollow out its content until they had soothed the uproar in the sovereign-debt market.

This is a valuable insight for two reasons, the first being that a crisis reminiscent of what Greece and other European countries went through a decade ago is an alien concept for practically all Americans, including our political leadership. Therefore, we cannot rely on their rationality in handling the crisis, once it happens; indirect information is the only valuable guideline we have.

The second reason why it is important to gain insight into how Congress would respond to a fiscal crisis is the fact that such a crisis is coming closer by the day. It is very unlikely that it will happen ‘now’—i.e., this side of the next presidential election—but it could very well take place in 2025. The stars are lining up, namely, for the simple reason that Congress chronically fails to address its structural spending problem.

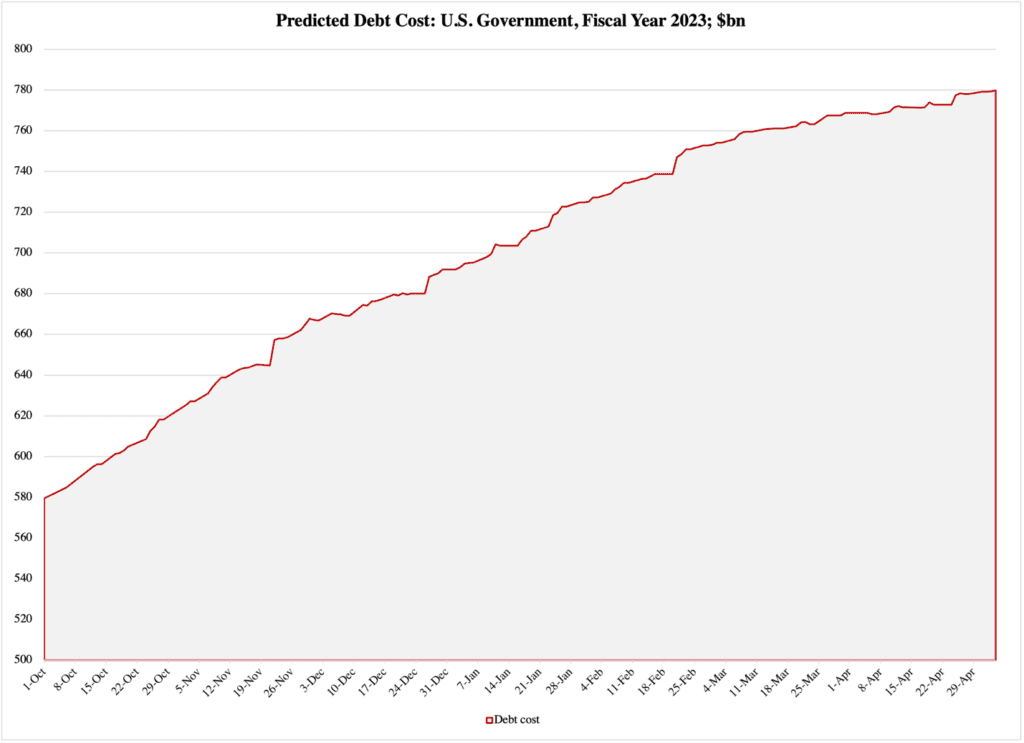

One key factor in predicting a U.S. fiscal crisis is the annual cost of the government debt. It eats up more and more of the federal budget, currently rising toward $800 billion for the year. Figure 1 shows how the predicted annual cost of the debt for fiscal year 2023 (Oct. 1, 2022 to Sept. 30, 2023) increases as the year unfolds:

Figure 1

Source of raw data: U.S. Treasury. Estimate made with fiscal forecast model developed by the author.

Technically, the cost trend is tapering off, giving the impression that it is going to flatten out somewhere between $780bn and $800bn for the whole fiscal year (which ends on September 30th). In practice, we can expect a sharp rise in the cost as soon as an agreement is in place for the debt ceiling. The current ceiling, namely, allows for a debt of $31,381.5bn. As of May 5th, the official debt of the U.S. government was $31,459.3bn; the difference, less than 0.025% of the total debt, is permitted under the law that defines the debt ceiling.

Once the debt ceiling is lifted, borrowing will once again take off. The current Republican proposal for a debt-ceiling increase of $1.5 trillion opens for more borrowing through March next year; a plausible outcome of the fledgling Congressional negotiations is that the ceiling increase is extended farther, and raised further. It is reasonable to assume that neither the Republicans nor the Democrats want the new agreement to end in 2024, at least not before the elections in November of that year. If it did, it would turn the entire election into fiscal fireworks, and if managed by level-headed leaders, neither party will want to take it that far.

The problem is that the farther they extend the debt ceiling, the higher they must raise it. When they raise it, they risk adding stress to an already distressed market for U.S. debt: again, there comes a point when Congress—regardless of its short-term debt ceiling deals—is facing such high costs for its debt that not even the most optimistic investors can continue to expect the U.S. Treasury to meet all its debt-cost obligations on time.

That is the point where sovereign-debt investors will want to rapidly, and significantly, reduce their holdings of U.S. debt.

At that point, panic sets in and throws rational policy thinking out the window. Members of both parties in Washington are well advised to try to avoid a situation like that. The sooner they start talks about structural spending reform, the better. The goal of such talks would be to close the deficit, in other words, to simply stop increasing the debt.

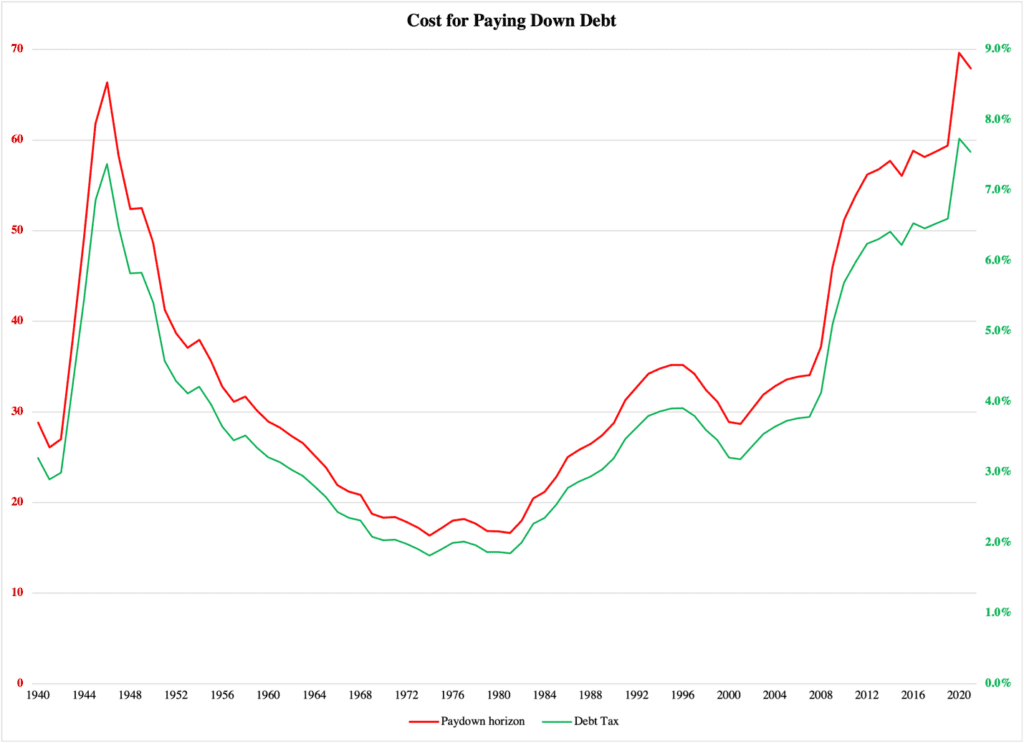

To expect talks in the foreseeable future about how to pay off the debt is to expect the impossible. We can all agree that this is unfortunate because the current debt is of such proportions that it is already difficult to pay back. Figure 2 illustrates the problem. The red line illustrates how many years it would take to pay back the government debt as it is today if America’s entire workforce paid a 3% debt paydown tax on their employee compensation. In the 1970s, the pay-off horizon was shorter than 20 years; in the 1990s it peaked at around 35 years; after the 2010s, just before the 2020 pandemic, the pay-off horizon was almost 60 years.

If we started today, it would take 70 years to pay off the debt with the 3% debt tax.

The green function tells us what the employee-compensation tax would have to be if we fixed the payoff horizon at 30 years. A tax that was less than 2% in the 1970s would have to be 8% today:

Figure 2

Source of raw data: Bureau of Economic Analysis

The calculations reported in Figure 2 are based on static assumptions, i.e., assuming that both the debt and employee compensation are frozen. However, even if we assume that total employee compensation in the U.S. economy from hereon were to increase by 4% per year (the average annual growth rate in the last decade), and take 3% from every employed person, it would still take 36 years, to 2059, to pay off the debt as it stands today.

So far, business as usual dominates the fiscal policy conversation here in America. It will be business as usual for some time still, but the point at which the usual is overshadowed by the unprecedented is coming closer every day.