On June 6th, the Budapest Business Journal reported that György Matolcsy, president of the Hungarian central bank, can see a possible Hungarian accession to the euro zone in 2030, but not earlier than that.

According to Hirado.hu, Matolcsy explained that it would be irresponsible of Hungary to try to join the currency union before that point in time. He pointed to how Greece and Slovakia joined the euro zone “unprepared” and paid a price for it.

The reference to Greece is important. A year ago, when Croatia was being approved for euro-zone membership, I noted that there was no real debate in Croatia over the possibility that the country would walk itself into a Greek fiscal trap. It was easy to get the impression, I explained,

that the Croatian government is trying to fast-track euro membership. This is unfortunate, especially since there does not seem to be much debate in Croatia over how the country can avoid ending up in the Hellish debt trap that Greece found itself in a decade ago.

In other words, Matolcsy’s reference to the macroeconomic disaster in Greece is essential. If Hungary were to join the euro, the country must be in such a position that there is no risk for a similar catastrophe there.

In addition to preparing its government finances—essentially the welfare state—for euro membership, the Hungarian government must also consider how the loss of its own currency can be compensated for in other ways. There are, namely, distinct advantages with keeping the forint.

In the past, these advantages have primarily taken two forms, the first being a slow depreciation of the forint vs. the euro. While there are downsides to a weakening currency, the benefits are clearly visible in the Hungarian economy today.

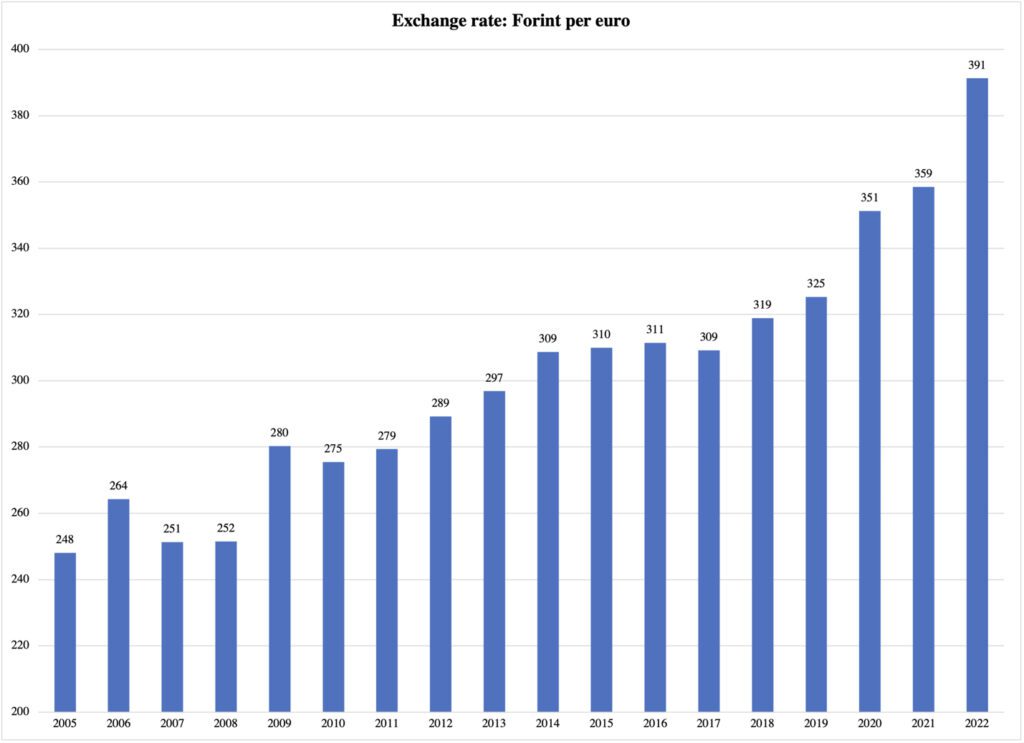

Figure 1 reports the annual average for how many forint it cost to buy €1:

Figure 1

Source: European Central Bank

Since 2005, the forint has depreciated vs. the euro at an average rate of 2.8% per year. This has contributed to the inflation that has plagued the Hungarian economy recently, but it also benefits businesses that export from Hungary to the euro zone.

To see how this works, suppose that in 2005, BMW starts building cars in Hungary. Suppose the cost of producing the car is HUF 2,480,000. This is the revenue that BMW needs in order to pay the costs of manufacturing the car. (We assume for simplicity’s sake that all parts are made in Hungary.) If it sells the vehicle to the euro zone at the average exchange rate for 2005, it can charge a price of €10,000 and still cover the production cost.

In 2006, the exchange rate was 264 forint per euro. Suppose that it still costs HUF 2,480,000 to build the same BMW. If they export it to the euro zone at the same price as the year before, the sales revenue is still €10,000. However, since the forint is weaker they get HUF 2,640,000 when they exchange that revenue. This is a 6.5% increase in sales revenue, or a 6.5% profit margin.

With a 2.8% average annual exchange-rate depreciation, Hungary makes a good case for itself as a manufacturing hub for euro-zone oriented companies. As I reported back in January, this advantage has manifested itself in an almost uninterrupted, two-decades long streak of surpluses in the flow of foreign direct investment capital. In practice, foreigners have invested more money in Hungary than Hungarians have invested abroad.

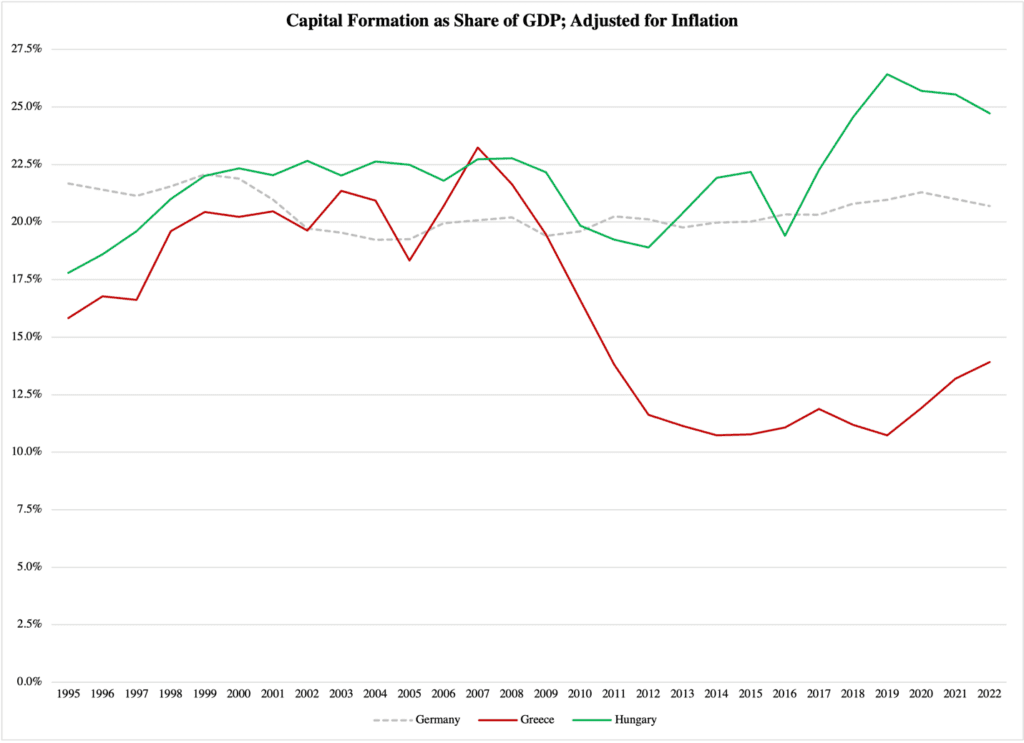

For the past 20 years, strong foreign investment has helped make capital formation, i.e., business investments, a bigger part of the Hungarian economy than in many other countries, including Germany. Figure 2 compares the investment-to-GDP ratio for Hungary, Germany and Greece. Since the turn of the millennium, capital formation has accounted for more than 20% of the Hungarian GDP:

Figure 2

Source of raw data: Eurostat

The strong trend of capital formation is tied to the slow currency depreciation:

In other words, during the period with more rapid currency depreciation, there was even higher growth of productive capacity in the Hungarian economy.

Normally, a country that attracts large amounts of foreign investments would see its currency appreciate. This has not been the case with Hungary (again limiting the comparison to the euro). There can only be one reason for this: the Hungarian central bank has run an accommodating monetary policy in order to avoid the growth-stifling effects of a currency appreciation.

When Greece plummeted into its fiscal crisis in 2009-2010, its central bank had no accommodating measures at hand. Its status as a mere branch of the ECB precluded any monetary response to the crisis.

As Figure 2 reports, the Greek crisis took some very tragic forms. One of them was the implosion of capital formation, which since 2010 has contributed only about 12% to the country’s GDP. This is of course very bad for the future of the Greek economy; since the start of the austerity crisis, Greece has gone backwards economically, including losing one-quarter of its GDP.

The catastrophe in Greece was made possible by its euro zone membership: sharing its currency with Germany, Greece effectively got Berlin as a co-signer on its government debt. As a result, they took on far more debt than their economy could pay for. All it took to make the unsustainability of the debt surface was for an economic downturn to tank tax revenue.

Their crisis was caused by unsustainable debt levels, brought about by the euro membership. As a result, when the crisis began, the Greek parliament had to focus all its fiscal resources on reducing its budget deficit. Called ‘austerity,’ this type of policy aims to reduce the budget deficit by repeatedly raising taxes or cutting government spending, or both. It was terribly bad for the Greek economy.

If Greece had never been part of the euro zone but had retained its own currency, it would have had the potential for succeeding economically in the same way that Hungary has. There is a good chance that Greece would have avoided its fiscal crisis altogether.

In fairness, even if Hungary joined the euro today, there would be no acute risk for a fiscal crisis. As I explained in December last year, the consolidated Hungarian government has consistently run budget deficits since at least the mid-1900s, without ever falling into the chasm of a fiscal crisis. As of the second quarter last year their government debt amounted to 77% of GDP. It is higher than what is permitted under the (basically toothless) EU Stability and Growth Pact, but not as high as it was in Greece, Italy, Portugal, Spain, France, and Belgium. They all had deficits above 100% of GDP.

However, if a crisis were to happen, Hungary would be at the mercy of the European Union and the ECB. This aspect of the euro membership brings us to the second reason why Hungary should maintain its own currency. Over the past 15-20 years, by virtue of its currency independence, the country has been able to depreciate the value of its government debt vs. foreign investors. This has, so to speak, made the debt look smaller than it really is, and postponed the point where investors potentially judge the debt as unsustainable.

One reason why there has not been a runaway debt crisis in Hungary is the persistently strong growth of the economy. By operating at or near full employment, and by—as mentioned—attracting significant amounts of foreign direct investments, Hungary has continuously grown its tax base. Government revenue has nearly kept up with government spending.

One downside of the depreciating currency is that investments in Hungarian treasury securities have lost value to foreign investors by the rate of annual currency depreciation. The Hungarian government has countered this with an innovative program to motivate its own people to invest in government debt.

Hungary has been able to achieve enormous economic success in the past 10-12 years, thanks in part to their currency independence. Judging from the comments by central bank president György Matolcsy, Hungary could possibly join the euro in 2030 or soon thereafter. Would such a membership be good for Hungary?

No, it would not, for three reasons.

1. The loss of economic policy independence

What many euro advocates do not realize is that with the loss of monetary independence comes loss of fiscal policy independence as well. As demonstrated by the austerity crisis a decade ago, which I analyzed in detail in my book Industrial Poverty, the euro zone’s integrity depends on its member states maintaining a cohesive fiscal policy. If some member states continuously exceed the limits of the Stability and Growth Pact, others have to be more fiscally responsible to compensate.

The practical consequence of this is that all member states are forced to concentrate their fiscal policy on reducing, or at least containing, their budget deficits. They cannot do what the Hungarian government has done for over a decade now: use fiscal policy to stimulate economic growth.

Bluntly speaking: under the euro, the government in Budapest will be demoted from leading their nation economically to stewarding its fiscal accounts. This will bring Hungarian economic prowess down to levels more in tune with lackluster European averages.

2. The decline of business friendliness

When the currency advantage is gone, Hungary can still be a magnet for foreign investors by keeping business regulations at a minimum, by maintaining its low taxes on corporate income, and by continuing to invest in its already strong workforce. However, when the room to use fiscal policy for business-friendly spending shrinks (as per point 1 above), Hungary has to rely more closely on its other business-friendly measures.

This in turn raises the risk that these measures run out at some point; you can only deregulate so far. The room for tax cuts is, of course, limited by the need to keep the government budget in good shape.

3. Political blackmail

When Hungary loses some of its advantages vs. other countries, competition for business investments will get stiffer. The government in Budapest will become the ‘buyer’ of foreign direct investment in a ‘seller’s’ market. Businesses interested in investing abroad can then make demands on their tentative host country that they cannot make today; given the trend of corporate political activism, this opens the door for the Hungarian government to be pressured into changing some of its non-economic policies in order to attract new investments.

The European Union could also gain a position to exercise political blackmail toward Budapest. While Hungary does not currently have a problem with runaway government debt, that situation is more likely under the currency union. If a fiscal crisis happens, Hungary has to seek help from the EU and the ECB in order to avoid a run on its debt.

It is almost a certainty that in such a situation, Brussels would subject Hungary to blackmail over Hungarian laws and policy practices that are not to the EU’s liking.

One need only study the austerity packages that the EU, the ECB, and the IMF forced upon Greece, and see what political concessions those three entities extorted from Athens in order to provide debt-crisis mitigation funds.

Hungary has done exceptionally well for itself outside of the euro. It would be unfortunate if the government in Budapest chose to jeopardize all its accomplishments by joining the currency union.