The world is full of bad theories of why we must socially and economically re-engineer human society. What they all have in common is that they advocate some kind of government takeover of the lives of individual citizens. There are varying motives behind such efforts to socialize people’s lives, but a common theme is that humanity is faced with some complex, abstract problem that can only be solved by a revolutionary transformation of our society.

These theories are not new to our century. They made a terrifying footprint in the last century, when classical Marxism was put to work in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe.

History knows the devastating results, but those experiences have not kept other re-engineering theories from gaining ground. One of them is known as ‘degrowth’:

Advocates of “degrowth” say that addressing climate change requires nothing less than a fundamental rejection of the whole principle of continuous economic growth as a policy objective. Their concerns have, slowly but surely, moved from the fringes of Europe’s policy debate to at least being granted a hearing in the EU institutions.

There is no other word for this line of thought than delusion. However, that does not prevent the ‘degrowth’ ideas from taking seemingly rational form. A ‘degrowth’ proposing article in Nature in December 2022 opened with a bombastic statement:

The global economy is structured around growth—the idea that firms, industries and nations must increase production every year, regardless of whether it is needed. This dynamic is driving climate change and ecological breakdown. High-income economies … are mainly responsible for this problem and consume energy and materials at unsustainable rates.

The authors of the article also claim that

Wealthy economies should abandon growth of gross domestic product (GDP) as a goal, scale down destructive and unnecessary forms of production to reduce energy and material use, and focus economic activity around securing human needs and well-being.

We should all welcome opportunities to use less resources to satisfy more human needs. However, this cannot be accomplished through economic commands, especially not those that are associated with the ‘degrowth’ theory. The reason is found in three analytical errors that this theory is guilty of:

Let us start with the last error. Implicit in the idea of a policy to “focus economic activity around securing human needs” is the premise that not all human needs are being met today, but that they can be met by government. This in turn suggests a desire to redistribute economic resources so as to reduce differences in the standard of living. In short: fight income inequality.

Regardless of the moral status of such a project, the economic thinking behind it is entirely wrong. The only way we could concentrate our economic policy on “securing human needs” instead of growing the economy is if we agree to provide for fewer human needs than we provide for today.

Degrowth advocates do not understand this, simply because they do not understand the concept of the gross domestic product, GDP. It is nothing more complicated than the sum total of all economic transactions that take place in a country, in a given period of time (normally a year). We measure these activities in three different ways: in terms of how economic resources are used; in terms of what is being produced; and in terms of what incomes these activities generate.

The use of economic resources is divided into five categories: private consumption, capital formation (or business investments), government spending, exports, and imports. By tallying up the activities in all these five categories (and technically subtracting imports from exports), we get the sum total of GDP in our country.

We can also measure GDP from the production side. Here, we do it by calculating the value added at every step of production. When a product is sold to its final user, we have the full value that it adds to the economy; when we add up the value of every product produced in or imported into the economy, we have GDP.

At every step where there is value added, there is also income generated. Just like with the other two ways to measure GDP, we add up the individual components—incomes—and get GDP.

All three ways to calculate GDP always add up to exactly the same number. That, however, is not the main point here: what matters is that the degrowth proponents are wrong when they believe that a shrinking GDP can help feed, clothe, house, heal, and educate more people. That is not at all the case: the more economic activity we have, the more resources we will have available to satisfy human needs of all kinds.

This creates a problem for those who advocate a welfare state—for the purposes of satisfying human needs on the basis of equality—and at the same time want to see a smaller economy. When the economy shrinks, the tax base shrinks with it. When the tax base shrinks, the maximum amount that government can extract from the economy will inevitably shrink as well.

It is not hard to see how economic stagnation, i.e., slow or no growth, leads to rationing in the welfare state’s entitlement systems. There are plenty of examples of this, primarily from Europe over the past 40 years.

In addition to the myth that a shrinking economy is better than a growing economy, people who look at GDP without any training in economics tend to think that it is all material production and consumption. That is not the case: in America and in most advanced economies, two thirds of what is produced and consumed are services. These services consist of anything from a haircut at the local barber shop or a ride with local transit to the surgeon that separates conjoined twins at the local hospital.

Over the past 60 years, roughly, the modern industrialized economies have gradually become dominated by services. This is also reflected in a relative—and in some cases absolute—reduction in the use of natural resources. There are more reasons why we are becoming more and more economically efficient: for one, we steadily make technological progress.

Most of the world operates under some sort of economic system where individual effort is rewarded while individual failure is allowed to cost. In this kind of economic system, those who learn to do more with less, and who can persuade us consumers that their products—whether goods or services—are better, will be duly rewarded by the free market.

In the aggregate, these incentives allow us to satisfy more human needs with relatively fewer resources than we did in the past.

This brings us to the other major error that degrowthers make, namely assuming that economic growth necessitates a linear increase in the use of natural resources. Those who make that claim are ignorant of the cold, hard numbers that show how we, the human race, are gradually reducing our consumption of the planet’s resources—while still increasing our prosperity.

Let us use oil consumption to illustrate this point. But let us start by acknowledging that in absolute numbers, the consumption of oil has indeed increased in recent human history. In absolute numbers, the world uses approximately 40% more crude oil now than it did 50 years ago.

To the crude, oily environmentalist, this is a sign that humanity is increasingly depleting the planet’s resources. This is not at all the case: the increase in oil production is slowing down, and it is doing so according to a promising trend. If we leave the global economy to operate on its own terms, global demand for oil will peak, and then start to decline—while we are growing more prosperous and can take care of more human needs.

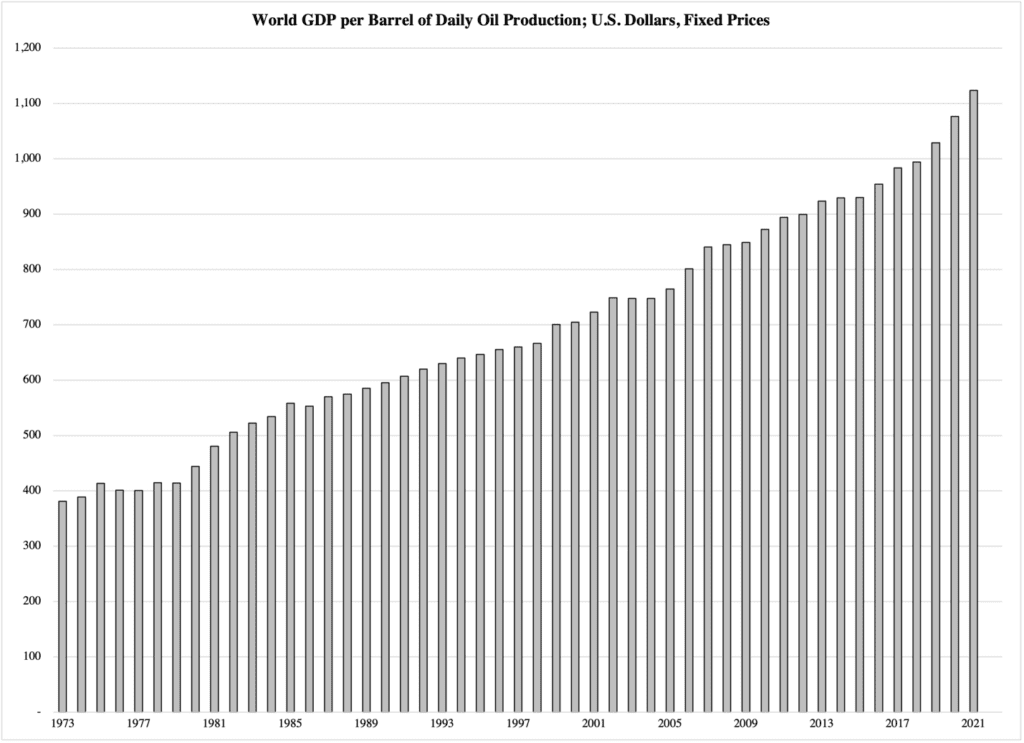

To see how we have grown more efficient over time, Figure 1 reports the remarkable growth in real GDP per barrel of daily oil production.

Figure 1

Sources of raw data: International Energy Agency (oil); United Nations (GDP)

If the degrowthers had been correct in that we are linearly consuming more of the planet’s resources, then the ratio in Figure 1 would be flat. The fact that it is rising over time is, again, evidence that our economic prosperity to a lesser and lesser degree depends on oil.

One reason why people tend to believe that our very livelihood rises and falls with oil production, is that news about oil prices tend to become big news. Most recently, we have been told that oil prices will rise in the near future because the cartel of oil exporters, OPEC,

and their allies are considering further cuts to oil production that could send oil prices soaring. The group, known as OPEC+ to include allies such as Russia, will … discuss another round of cuts to production for member countries, this time as much as 1 million barrels per day.

Fox Business adds that President Biden worries about this. Together with political leaders in other Western countries, the Biden administration claims that already implemented production cuts “have sent energy prices soaring.” They also lament that OPEC countries “have taken the side of Russia” over the war in Ukraine.

The long trend toward less oil dependency suggests that for every year, we become a little bit less exposed to radical swings in the oil price. That is not to say the oil price is insignificant: it is not. However, the main problem with the oil price is that it is volatile over time. As Figure 2 reports, courtesy of Macrotrends.com, the spikes in the oil prices that the world experienced in the 1970s, while new at the time, are in retrospect not unique. Oil has been expensive recently—in particular in the first 15 years after the turn of the millennium—but more than the higher price level, the oil market has been plagued by increased price volatility. In general, price volatility is a bigger problem than high, stable prices, simply because volatility makes it harder to predict the future.

The one problem we have currently is that high price volatility is combined with a long-term trend of rising prices. This trend has been ongoing for approximately a decade now:

Figure 2

Source: Macrotrends.com

There is no doubt that our economy is affected by both rising and volatile oil prices. The point, again, is that our exposure to oil and its price fluctuations becomes less pronounced over time. The American economy’s dependence on oil is lower than it has been in a century and continues to decline.

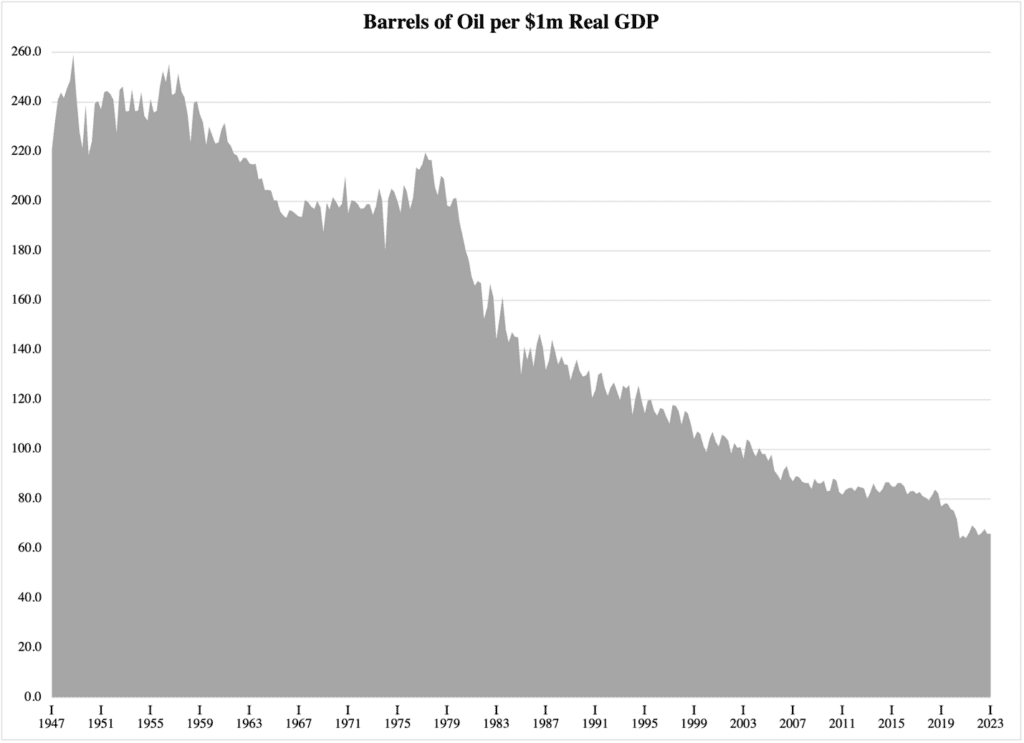

Figure 3 reports the same relationship between GDP and oil consumption as Figure 1, but this time it calculates the barrels of oil needed to produce $1 million worth of GDP. Its message is compelling: the U.S. economy needs less and less oil. The amount of crude oil needed to produce $1 million worth of inflation-adjusted GDP, has fallen by 75% since World War II.

Figure 3

Sources of raw data:

Energy Information Administration (Oil); Bureau of Economic Analysis (GDP)

This increased efficiency is not isolated to oil. It cuts across all resources we use. Instead of throwing wrenches into the prosperity machine that is the free-market capitalist economy, and instead of trying to force it into using less resources, we should give ourselves and our ingenuity a chance to continue to improve our lives.

Instead of trying to do less with less, let us continue to do more with less. That is how we elevate more people out of misery, poverty, starvation, and famine. And save the planet in the bargain.