Based on the public narrative about Hungary, you would think the country was some kind of semi-totalitarian mess, adrift in chaos and despair. Reality is a galaxy away from this myth: Hungary is one of Europe’s most solid democracies, and has one of the strongest, best functioning economies in the EU.

For reasons I shall not comment on, the Hungarian economic success story has been completely ignored in the public discourse. That is unfortunate, to say the least: many countries in Europe (and beyond, frankly) have a great deal to learn from Hungary.

In its latest news release on economic growth, Eurostat reports that Hungary is one of eight EU member states with a growth rate above 4% per year. At 4.1% in the third quarter, the country is leaps and bounds ahead of Europe’s two largest economies, Germany (1.3%) and France (1.0%). This is nothing new: for the past decade, the Hungarian economy has consistently placed itself among the top 5 in Europe, being an attractive destination for foreign direct investment, and having a tax code that promotes both private consumption and capital formation.

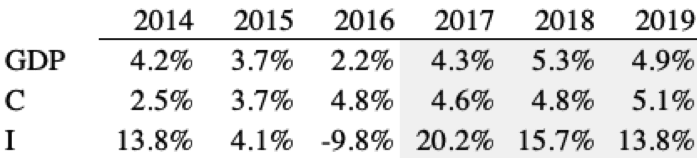

The best way to understand the thought leadership behind Hungary’s economic success is to examine the 2016 tax reform. It had a strong impact on an already well-performing economy, stimulating higher growth rates in gross domestic product (GDP), private consumption (C), and business investments (I). Post-reform numbers are shaded in Table 1:

Table 1

Reflecting these Europe-leading numbers, the labor market is remarkably strong. The rate of the population that holds a job was below 45% prior to the tax reform. It was increasing, but also showing signs of flattening out.

After the 2016 reform, the rate continued to rise strongly. It passed 47% in 2018 and 48% in 2021. So far in 2022, it stands at 48.5%.

This ratio is not one of the highest in Europe, but the purpose behind the reform was not to maximize employment at all costs. The idea was instead to give families more flexibility in the choice between workforce participation and family life. That is why the Hungarian workforce participation ratio is lower than in socialist welfare states like Sweden, Finland, and Denmark, where the tax system prioritizes workforce participation at the expense of family life.

One of the most intriguing features of the tax reform was the KATA (Hungarian acronym) tax on small businesses. It came out of the reform with three essential components:

This is quite possibly the simplest small-business tax in the world. The lump-sum feature is ingenious: since it is independent of the revenue of the business (up to the income cap), its share of total revenue declines with rising income. This gives the business owner an incentive to work more and earn more. Its simplicity also relieves the business owner of almost all paperwork.

Making KATA-eligible businesses VAT exempt is a real blessing. If there is one tax that comes with an abundance of red tape, it is the VAT. Not having to pay it is a major cost saving for small businesses.

Needless to say, the KATA tax has made it easy to start, operate, and grow a business. In the year when the parliament in Budapest passed the tax reform, 7.2% of all working Hungarians were self-employed. In 2022, that share is 9.3%. From 2016 through 2022, self-employment has accounted for 48% of all new jobs created in Hungary.

This is without comparison the highest rate in Europe. Estonia, which comes in second, can only attribute 23% of all new jobs in the same period to self-employment. In ten EU states, the number of self-employed individuals actually declined.

It deserves to be mentioned that the self-employment status is not automatically identical to KATA eligibility, but given the architecture of the tax, it is reasonable to assume that the two categories overlap substantially.

In addition to the world-class small business tax, the Hungarian tax reform also lowered the overall tax burden on the economy. It raised the ceiling for tax-exempt business assets and raised the threshold for when a business must begin to pay the VAT. The reform also simplified the income-based health care tax, while exempting dividends and capital gains. A tax break for investments was introduced, limited in scope but designed to be particularly helpful for small businesses.

The results of the reform are visible in Eurostat’s public-finance statistics in the form of a declining total tax burden:

In addition to easing the burden of government on the economy, the tax reform also accelerated the tax-revenue growth rate. In 2012-2016, the five years preceding the implementation of the reform, total tax revenue grew by 5.5% on average; in 2017-2021, the first five years after the tax reform, that growth rate was 7%.

Since these are current-price numbers, it could be said that the higher rate was the result of higher inflation in the second period: 3.3% per year compared to 1.6% per year in the first period. However, since the tax reform actually lowered the tax burden, inflation cannot be the cause of the higher revenue growth rate.

This was a so-called supply-side tax reform, designed to stimulate economic growth. Such reforms are often criticized for causing higher deficits (see, e.g., David Stockman’s well-written The Great Deformation and my own e-book Tax Cuts Don’t Work). The American tax reform in 2001 and 2003, under President George W. Bush, took several years to deliver a reduction in deficits, and the 2017 reform under President Trump never showed any sign of a shrinking deficit.

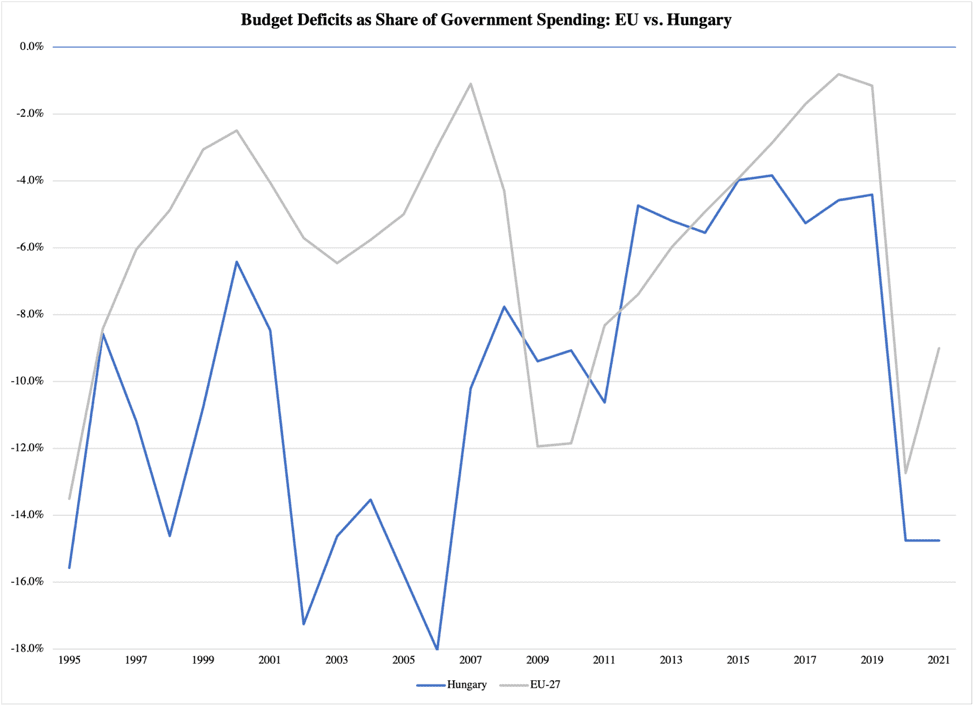

By contrast, the Hungarian tax reform substantially improved public finances. Figure 1 reports the budget deficit in Hungary (blue line), compared to the deficit in the EU as a whole (gray), as percent of total government spending. It is striking how Hungary, before the Great Recession of 2009-2011, had considerably worse public finances than the EU-27 countries, and how the budget balance began improving under Prime Minister Orbán (please note that the scale is negative, as it reports budget deficits):

Figure 1

Notably, there was no increase in the deficit at all after the 2016 tax reform. The steep rise in 2020 and 2021 is the result of the artificial economic shutdown during the pandemic and has nothing to do with fiscal policy.

It is a valid point of concern that Hungary still has budget deficits, but no more so than for any other country where government borrows money on a regular basis. If anything, the Hungarian budget deficit is less of a problem to the country’s economy than deficits in other countries. As I noted back in August, Hungary has an economic-growth provision attached to its fiscal-policy framework which states that

when parliament passes the annual budget, it does so based on a forecast of GDP growth that is written into the appropriations bill. If the economy grows in excess of the budget forecast, all tax revenue derived from that extra growth will go toward paying down the budget deficit.

There is also a policy in place to spread ownership of the government debt among Hungarian families. This increases public engagement in government affairs and provides a safe savings opportunity alongside such long-term equity builders as home ownership.

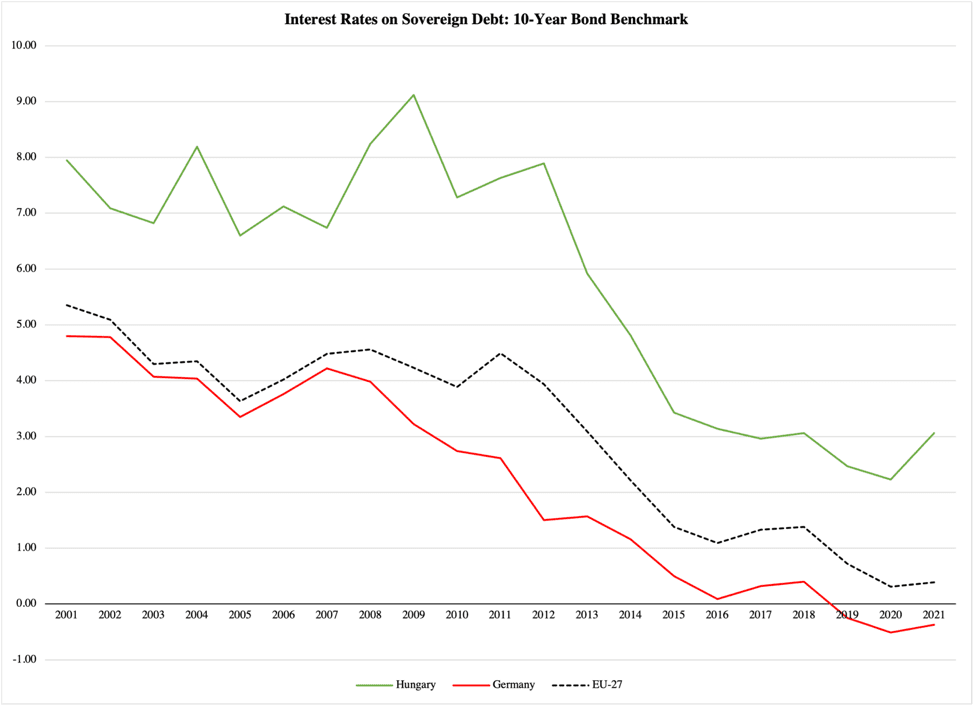

As mentioned, international investors have shown confidence in the Hungarian economy, with strong foreign direct investments. This confidence is also visible in declining interest rates on the country’s sovereign debt. Figure 2 reports the rates on 10-year government securities (harmonized according to Maastricht standards) for Hungary and the 27-member EU. Germany is thrown in for comparison, as it is often seen as a public-finance benchmark:

Figure 2

With all this in mind, not everything is perfect in Hungary. Inflation is high, exceeding 20% in October, and in August, the Standard & Poor credit-rating firm added a negative outlook to Hungary’s rating. Furthermore, this summer the Hungarian parliament changed the KATA tax law to limit its applicability.

None of these problems pose any serious threat to the Hungarian economy. If inflation was coupled with high and rising unemployment rates, there would be cause for alarm, but this is not the case in Hungary. Its labor market remains strong, with few signs of weakness in coming months. Given the nature of inflation, it is safe to predict that it will subside over the winter months, possibly sooner than that. Other European countries have much bigger reasons to worry about inflation, among them Sweden, with one of Europe’s highest unemployment rates and a major real-estate bubble about to burst.

Frankly, it is a bit puzzling to see Standard & Poor’s pessimistic credit outlook for Hungary. It simply does not match up with the facts on the ground in the economy. Overall, Budapest has done a phenomenal job of combining three difficult economic-policy goals: promoting economic growth and full employment, funding a welfare state, and avoiding excessive budget deficits. Europe is littered with evidence of how hard it is to herd these three cats at once, but Budapest has managed to do it.

The changes to the KATA tax are a bit more problematic. As explained earlier, the tax clearly helped give the Hungarian economy a growth boost, and it has been instrumental in growing entrepreneurship as well as providing important liquidity on the margin in the pockets of Hungarian households. With its recent changes, the parliament in Budapest took the risk of possibly weakening a strong feature in one of Europe’s best entrepreneurial economies.

At the same time, the Hungarian government makes a valid point in motivating the reform:

According to the Hungarian Ministry of Finance, the new amended rules are necessary as certain employers were forcing their employees into a KATA tax status. It was discovered that some employers were not registering workers and paying the required tax and duties on their wages.

In other words, the intention is to return the KATA tax to its original purpose. It is also understandable if the reform aims to increase tax revenue at a time when the effects of the 2020 pandemic are still lingering in public finances.

The reform may turn out to be beneficial in the long term, especially since the government has taken additional steps to mitigate the negative consequences of the KATA reform. As of now, though, Budapest has to walk a fine line, especially in terms of tax policy and business-related regulations. The best advice for the Hungarian government is to work on reinforcing confidence among entrepreneurs that taxes and regulations are going to be predictable and simple going forward and to avoid other measures that can contribute to increased economic uncertainty.

I have a feeling that these pieces of advice will turn out to be redundant. Hungary is blessed with competent leadership. Currently, things may look a bit tough here and there, but if the government in Budapest has shown anything in the past decade, it is that they possess a remarkable sense of resiliency and that they know how to govern with focus on the country’s long-term path to prosperity.