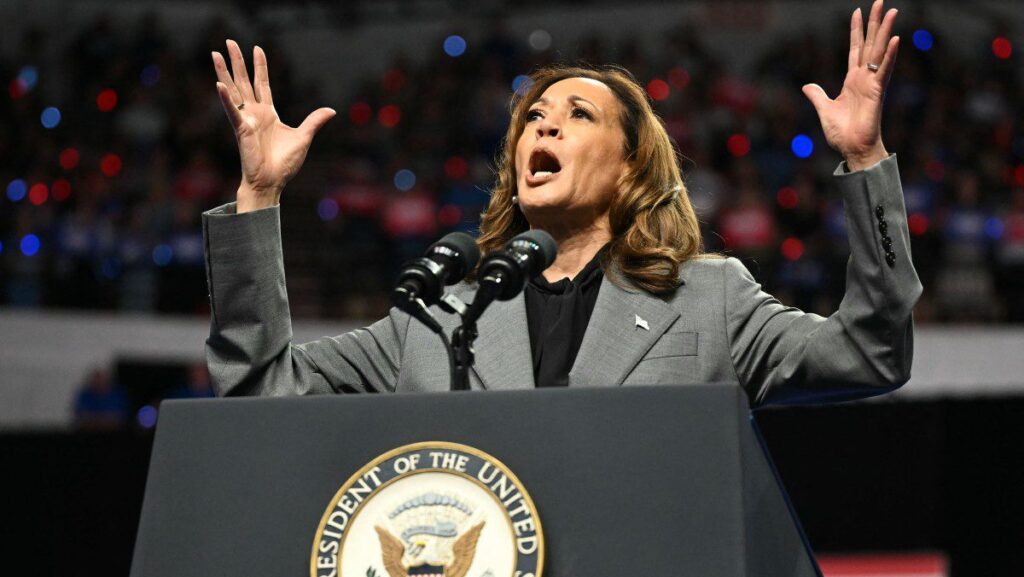

U.S. Vice President and Democratic presidential candidate Kamala Harris speaks at a campaign event at Alliant Energy Center in Madison, Wisconsin, on September 20, 2024.

Photo: Mandel NGAN / AFP

Two weeks ago, Democrat presidential candidate Kamala Harris finally released a list of policy issues that she said she would fight for if elected president. One does not have to read much about her policy proposals to see that she is no longer hiding her hard-line leftist ideological ambitions.

It is easy to criticize left-leaning policies on their ideological merits, but it is just as necessary—if not more—to pinpoint the flawed economics that goes into something so blatantly ideological as Harris’s policy platform.

She has centered her economic policy ideas around the concept of “opportunity economy.” As is usually the case in politics when candidates merrily employ ill-defined slogans, it is impossible to find any publication—by Kamala Harris or her campaign—that nails down what an “opportunity economy” actually is.

Or, to be more precise: she has thus far failed to explain how her opportunity-based economy is different from the opportunity-based economy that currently exists in America.

Since the Harris campaign does not define the term, our only hope to rein it in semantically is to comb through the actual policy proposals on the “Issues” page of her campaign website. Since the “opportunity economy” is prominently mentioned there, we can safely assume that those policy proposals are in some way meant to give content to her lead policy slogan.

Unfortunately, a review of her policy ideas brings us no closer to a workable definition of the opportunity economy. Most of what it contains could easily be sorted under America’s already existing welfare state. Just like it, Harris’s policy ideas want to take America further in the leftist direction.

A representative example is the return to the $3,600 child tax credit—almost twice the current level—that was handed out by Congress during the 2020 and 2021 pandemic. There is also the proposal for a supplemental child tax credit of $6,000 “to families with newborn children.”

Both of these would ostensibly come with the same kind of eligibility structure that the current child tax credit does. This means that a family cannot qualify for them unless their taxable income is below a certain level. Since that level happens to be $200,000, very few families will fail to qualify for it. Therefore, from a structural viewpoint, the two child-tax credit ideas that Kamala Harris has proposed would de facto work like universal benefits.

Another item on Harris’s wish list is an expansion of the so-called Earned Income Tax Credit, EITC. It is unclear exactly by how much she would expand it, but some news outlets suggest $1,500 per eligible household.

From an ideological perspective, Kamala Harris’s proposal to expand the EITC is significantly more contentious than her child tax credit ideas. The EITC is the quintessential socialist welfare state benefit program: it explicitly benefits some citizens at the expense of others, and the sole criterion for separating the two groups is how much money they make.

The best way to illustrate how the EITC is economically redistributive is to look at how the program benefits are paid out. This benefits program, which was created under President Nixon half a century ago, is a so-called refundable tax credit; in practice, it is a traditional cash-benefits program.

Aimed at providing a cash boost to working families, the EITC is designed to pay out lower benefits the more the family makes. This has two consequences, one intended and one unintended.

The intended consequence is that the EITC leaves the lowest-earning households with more money than they would have if they relied solely on their work-based income. Let us wait a moment with the unintended consequence.

Figure 1 illustrates the benefits from the EITC (green) for a family of two working adults with two children. As the income rises (gray columns), the family pays more in income taxes (red) and loses EITC benefits:

Figure 1

Now for the unintended consequence of the EITC.

The combination of a rising income tax and declining EITC benefits leads to a significant tax wedge between the family’s nominal income (as illustrated by the gray columns in Figure 1) and the income after taxes. Figure 2 combines the taxes and benefits from Figure 1 and deducts them from the pre-tax earnings. The net result is reported by the blue function:

Figure 2

The income tax rate remains unchanged throughout the income bracket in this example. This was not the case when I presented a similar analysis in my book The Rise of Big Government (Routledge, 2018); the numbers I used then were from the U.S. tax code as they looked before the Trump tax cuts. Back then, I pointed out that the interaction between EITC benefits and the federal income tax created a de facto marginal income tax of 36%:

To pay a marginal tax higher than 36 percent they would, by 2016 tax rates, have to make $467,000.

With the Trump tax reform, the de facto marginal tax on EITC-eligible households has fallen to 33.1%. To pay that much on their last earned dollar, they now would have to earn just over $693,000.

Again, these marginal tax effects are from the EITC alone; no other benefits programs are included. With that said, though, the marginal tax effect on personal income is not to be taken lightly, especially at such low incomes as in the EITC example. Consider a family with two incomes adding up to $30,000 per year. Thanks to the EITC benefits they get, their net income is $33,040—just over 10% more than what they earn from work.

Suppose one of the parents is offered a promotion at work. The added income would take their total family earnings to $55,000. As the benefits taper off and the income tax bill rises, the $55,000 turns into an income after tax of $49,775. What started out as an 83% rise in their pre-tax, pre-benefits earnings ends up being a rise of just above 50%.

That is still a sizable boost in income, and the parent offered the new job will probably take it. However, as mentioned, the EITC is far from the only benefits program offered by the U.S. government to low-income families. The same demographic is eligible for Medicaid—a tax-funded health insurance program—as well as SNAP, which provides grocery-buying assistance. There is also a federal energy assistance program for the payment of electrical bills and an ‘affordable’ housing program, just to mention a few.

We do not know at this point what income thresholds Kamala Harris wants with her other benefits proposals, such as giving $25,000 as assistance to first-time homebuyers. She also wants to expand tax-paid assistance to people buying health insurance, again without any eligibility details attached.

At the end of the day, all that seems to fit under the “opportunity economy” moniker is a row of traditional socialist ideas for economic redistribution.