Once again, Democratic presidential contender Kamala Harris has declared that she wants to ‘tax the rich’ to pay for her desired expansion of the American welfare state. In a recent interview with CBS 60 Minutes, Harris again beat the drum of economic redistribution, explaining:

One thing that I’m gonna make sure is that the richest among us, who can afford it, pay their fair share in taxes.

The term ‘fair share’ is a rhetorical staple among the Left. It is also the most un-defined concept in the political vocabulary: not one proponent of ‘fair share’ taxes on ‘the rich’ has ever produced a coherent definition of either ‘fair share’ or ‘the rich.’ To her credit, Kamala Harris comes a little bit closer to doing that: alongside her usual socialist rhetoric on economic redistribution, she has proposed a so-called minimum tax on the very wealthy. It would impose a 25% minimum income tax on taxpayers with a wealth of $100 million or more.

This tax apparently defines both ‘fair share’ and ‘the rich’, with the former being the 25% minimum tax and the latter being anyone with assets worth at least $100 million. This leads to an oddity that nobody on the Left has recognized (or perhaps bothers to straighten out): the 25% ‘fair share’ tax applies to income, but the liability to pay the tax is defined in terms of wealth.

Behind the tax lies the implicit premise that people who are worth $1oo million or more make a lot of money. That is a fair assumption, of course, but the correlation between wealth and income is far from certain. Wealthy people rely predominantly on their assets to produce income; wages and salaries account for less than a third of total income for people with $2 million or more in annual income.

When their investments work out as planned, they make good money, i.e., earn a stream of income that consists of stock dividends, interest, capital gains, and business profits. When, on the other hand, times are tough and their investments produce a loss, there is no income to be derived from those assets.

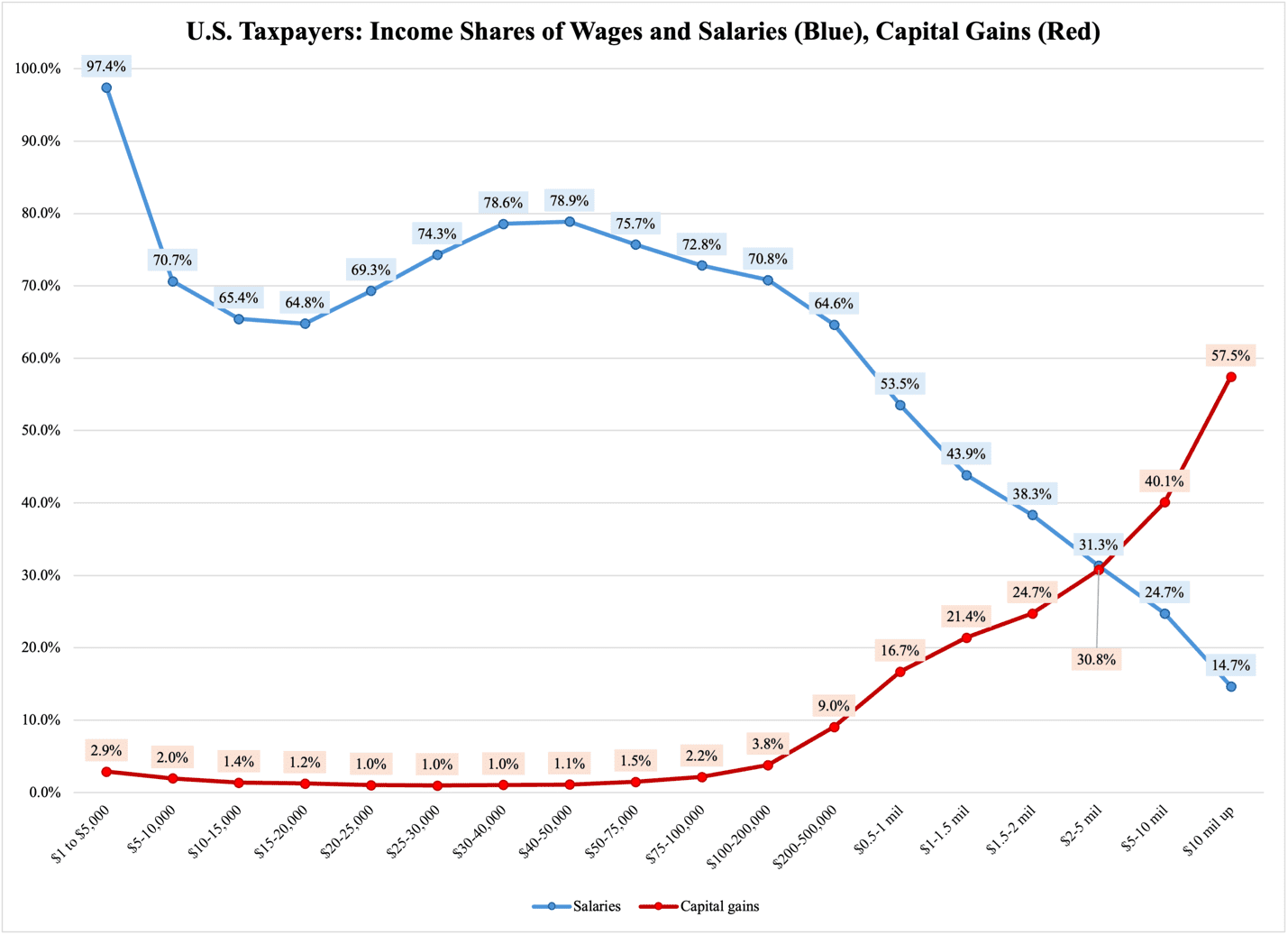

Due to the significant risks associated with reliance on equity for income, that very income is taxed more leniently than wages and salaries are. This gives the impression that the tax system lets ‘the rich’ get off the hook more easily than workers who rely on paychecks to feed their families. Figure 1 helps us see how this works. It reports the shares of total income that come from, on the one hand, wages and salaries (blue line) and, on the other hand, capital gains (red). As one would expect, the wage-and-salary share dominates among households with low-to-middle incomes, while capital gains dominate among taxpayers with high and very high incomes:

Figure 1

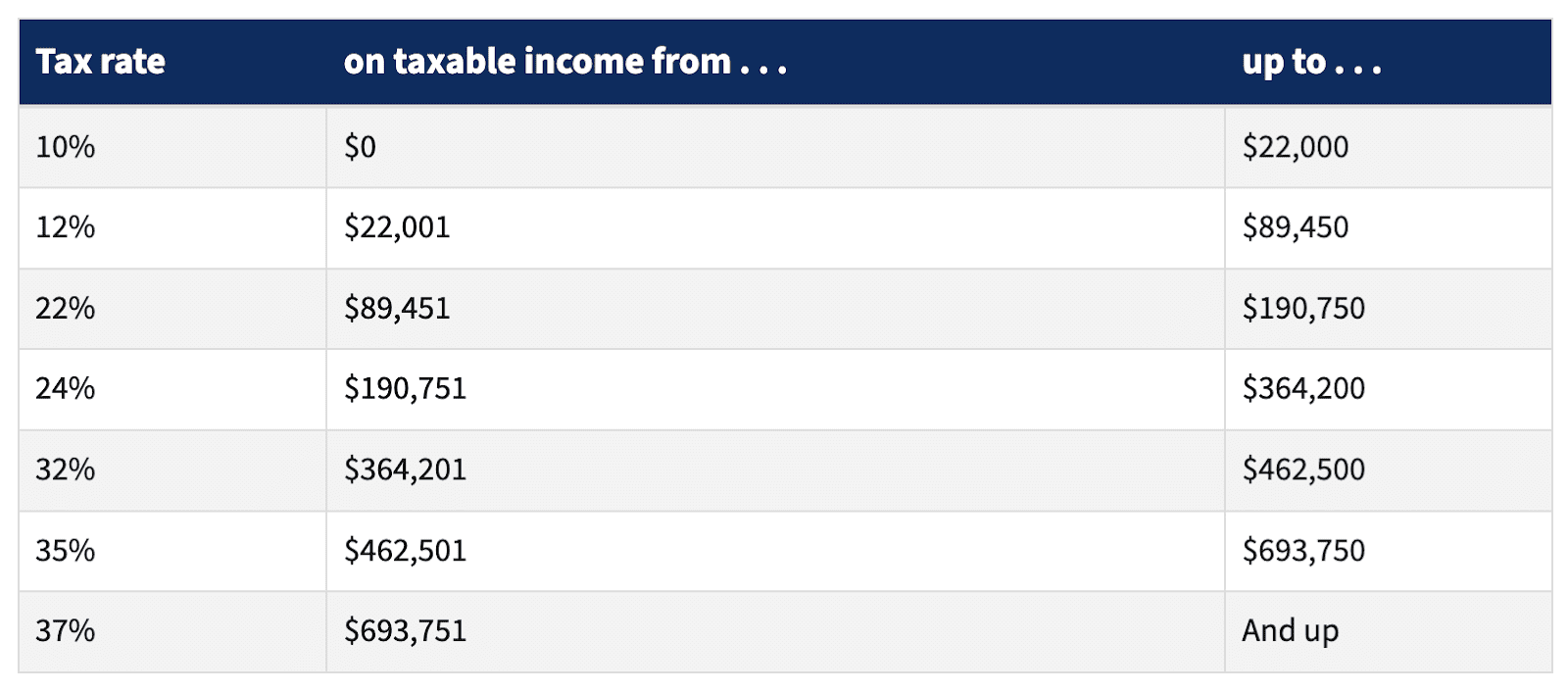

Wages and salaries, and other incomes that are classified equally, are taxed as follows in 2024 (assuming the taxpayers are a married couple filing taxes jointly):

Table 1

Suppose the married couple Joe and Jane make $100,000. Before they apply the tax table above, they make the standard deduction that every individual taxpayer is eligible for. In the case of a married couple, this amounts to $29,900; once the remaining $70,100 has been sliced up between the various tax brackets in Table 1, the couple ends up owing the IRS $7,948 (payroll taxes not included).

Suppose a wealthy married couple, Tom and Tricia, have $100 million in the bank. They do not work, but rely instead on capital gains. Those gains happen to be $100,000. Due to the more lenient taxation of some equity-based income, their first $94,050 is tax-free; they pay 15% on the remaining $5,950, which is $892.50.

This makes for an average tax on their entire income of 0.89%.

So far, Kamala Harris seems to have a point: Tom and Tricia pay virtually no taxes at all on their income. Therefore, let us add the 25% minimum tax to Tom’s and Tricia’s tax liability and see what happens.

As mentioned earlier, this tax applies to unrealized capital gains. This fancy term has a perfectly mundane meaning: it is the value increase in assets that you keep over time. However, let us assume for a moment that the 25% tax is applied simply and straightforwardly to Tom’s and Tricia’s $100,000 income. In this case, they now pay about three times as much in taxes as Joe and Jane do—on the same income.

Is this fair? Of course not. All we have done now is put the shoe on the other foot: the two incomes are still taxed differently.

But, says the proponent of ‘fair share’ taxation, the wealthy people can afford to pay a high income tax. After all, they have a lot of money in the bank.

Yes, they do, but that does not mean they can just go ahead and liquidate assets whenever they need to pay taxes. If Tom and Tricia have tied up their assets in a major investment, and the investment is losing money, they cannot just sell it to obtain cash to pay taxes.

So far, our attempt at fair-share taxation has failed, but we also have to recognize that the tax that Kamala Harris proposes is not supposed to work this way. As mentioned earlier, it is supposed to apply to unrealized capital gains, which makes life a whole lot more complicated for Tom and Tricia.

Suppose they have invested their $100 million in the stock market. Over the course of a calendar year, the value of their stock-market portfolio rises by 5%. They do not sell their stocks, just note with satisfaction that they are now worth $105 million, and then go about their daily lives.

Since they have not sold the stocks, they have not realized the $5 million capital gain they made. But Kamala Harris wants them to pay a 25% tax on that unrealized capital gain.

Suddenly, they have to cut a check to the IRS for $1.25 million—and if the stock market had a bad year, their income could very well be no more than $100,000. To meet their tax obligation, Tom and Tricia now have to sell stocks, and do it in a bearish market.

Is this fair? No, it is not. Yes, they are wealthy, but that does not change the fact that they have to sell a significant amount of assets to pay a recurring bill. This violates a host of principles for how to soundly manage a free-market economy.

The problem with Kamala Harris’s idea for a tax on unrealized gains is just that: it is a tax on gains without an equivalent tax deduction when the taxpayer takes losses. This makes long-term investments particularly unattractive, as they are almost always associated with losses in one form or another. At this point, capital will want to move abroad, where the tax climate is more sound and where entrepreneurs can safely start new businesses.

No matter which way we turn, Kamala Harris’s tax on unrealized capital gains is a clumsy, immoral, and economically ineffective tax. It is driven solely by socialist greed: tax the rich, no matter the consequences.