I predicted this. Back in August, when Fitch Ratings downgraded the U.S. government’s credit status, I warned that there would be more to come. I noted that President Biden, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, and Congress were all unwilling to respond responsibly to the downgrade. Therefore, I predicted:

Based on the reactions to the downgrade from America’s political leadership—deafening silence of defiant denial—we should expect more downgrades in the next 6-12 months.

That was three months ago. On Friday, November 11th, credit rating agency Moody’s made a ‘downgrade pending’ announcement. They explained that they have put the U.S. government on a negative credit outlook, which means that unless they see explicit reasons not to downgrade the U.S. government, they will do it.

Their report, which is available with free registration, opens with political dynamite in the form of a serious warning:

The key driver of the outlook change to negative is Moody’s assessment that the downside risks to the US’ fiscal strength have increased and may no longer be fully offset by the sovereign’s unique credit strengths.

These words should put both Congress and President Biden on full alert. The message is blunt:

If this warning came from some generic media commentator, it would not carry much weight. But Moody’s is nothing of the sort. They are one of the world’s most established credit rating agencies. When they speak, investors take note; one need look no further than at the European debt crisis a decade ago to see what weight credit-rating agencies carry.

Analysts have generally failed to pick up on the gravity of the Moody’s report, probably because it is not a formal downgrade. This is a mistake: the negative outlook is a shift in their default credit-rating assessment: so long as the rating remains stable, they need explicit reasons to change it; once the rating is shifted to negative, they need explicit reasons not to change the credit rating itself.

The default shift—from ‘no downgrade’ to ‘downgrade’—will have material consequences for the United States Treasury as it continues to borrow money. At the top of the list of those consequences is a new risk premium: this warning from Moody’s explicitly says that the U.S. government is no longer a risk-free borrower on the market for sovereign debt. Therefore, the Treasury will have to add an interest rate premium when it sells new debt at its regular auctions. Even as interest rates decline for other reasons—one being that inflation has fallen to less-abnormal levels—the Treasury will only be able to sell new debt if it marks up its bills, notes, and bonds to account for the rising credit risk that Moody’s points to.

Never before in the history of modern sovereign debt markets has the United States government been forced to pay a risk premium to borrow money.

Furthermore, the message that a formal credit downgrade is coming by default, is a troubling assessment of the institutional status of the United States government. There is a widespread idea among American politicians, as well as among many experts at think tanks, research institutions, and even in academia, that ‘we’ are impervious to the normal credit-market rules that apply to other countries. The reason often given is that the U.S. dollar enjoys the special status of global reserve currency.

It is correct that the dollar has functioned as the reserve currency since the days of the Bretton-Woods system. However, as I have explained in previous articles, the BRICS group is hard at work to de-dollarize the global economy, and they can use the U.S. indebtedness as leverage to weaken the dollar. Now, for the first time, a credit rating agency makes explicit the connection between the debt and the status of the dollar. Explains Moody’s:

For a reserve currency country like the US, debt affordability—more than the debt burden—determines fiscal strength. As a result, in the absence of measures that limit the size of fiscal deficits, fiscal strength will increasingly weigh on the US’ credit profile.

In other words, as the reserve currency status erodes, that “fiscal strength” weakens rapidly. It does not take a complete abandonment of the dollar on the global scene to make this happen—far from it. The reserve currency foundation of the U.S. government’s credit reliability is lost when there has been a ‘sufficient’ erosion of the reserve status of the dollar.

At this point, nobody can reliably predict at what point that status is lost; there is no precedent in history to build forecasting upon. However, this only makes the current situation all the more tenuous: while we cannot say when the decline in the reserve currency status will increase the risk premium on U.S. debt, we do know that when it happens, American interest rates will rise sharply, rapidly, and painfully.

From a political viewpoint, the most apparent consequence of the Moody’s report is that the United States government is now gradually losing its fiscal sovereignty. It is increasingly likely that 2024 will be the year of the fiscal crisis—one that this country has never before experienced. I warned about this already back in July; we are now in the preamble to a fiscal crisis: gradually, the authority of Congress to determine taxes and spending will be transferred to institutional actors on the sovereign debt market.

Congress can still prevent this preamble from escalating into a full-fledged fiscal crisis, but their list of options is getting shorter. In the coming weeks and months, one of two scenarios will unfold. They are very different but—at least for now—equally probable; the difference between them illustrates how genuinely uncertain America’s long-term economic future has become.

Under the first scenario, there will be no fiscal crisis. If Congress wants to make this scenario happen, they need to combine the statement from Moody’s about reining in deficits with the following point further down in their report:

At a time of weakening fiscal strength, there is an increased risk that political divisions could further constrain the effectiveness of policymaking by preventing policy action that would slow the deterioration in debt affordability. These risks underscore rising political risk to the US’ fiscal position and overall sovereign debt profile.

After referring to recent events that exemplify legislative stalemate, including the ouster of Speaker Kevin McCarthy, the report suggests that this “political polarization is likely to continue.” For this reason, they explain,

building political consensus around a comprehensive, credible multi-year plan to arrest and reserve widening fiscal deficits through measures that would increase government revenue or reform entitlement spending appears extremely difficult.

The analysts at Moody’s could not have spelled it out any more clearly. This ‘The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Avoiding a Credit Downgrade’ screams to House Speaker Mike Johnson and Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer: ‘Please give us a debt commission.’

As I explained last week, a commission of the kind that Speaker Johnson has mentioned is not going to solve the structural deficit problems in the federal budget. However, that is not what Moody’s wants to see, at least not right now. All they want is the show of bipartisan efforts to avoid a looming fiscal crisis. They ask for activity, not results.

If the House and the Senate moved quickly, they could have a formal proposal for a commission in place before the Federal Reserve’s Federal Open Market Committee, FOMC, holds its next meeting on December 12-13th. At that meeting, the FOMC will consider whether to raise interest rates one last time this year. Back in August, I predicted that the Federal Reserve would make at most one more rate hike this year. With inflation down to moderate levels—the November CPI number is 3.24%—there is less incentive for a rate hike.

The FOMC could raise its funds rate in response to Congressional fiscal irresponsibility; with a debt commission on its way, that motive for a rate hike is gone.

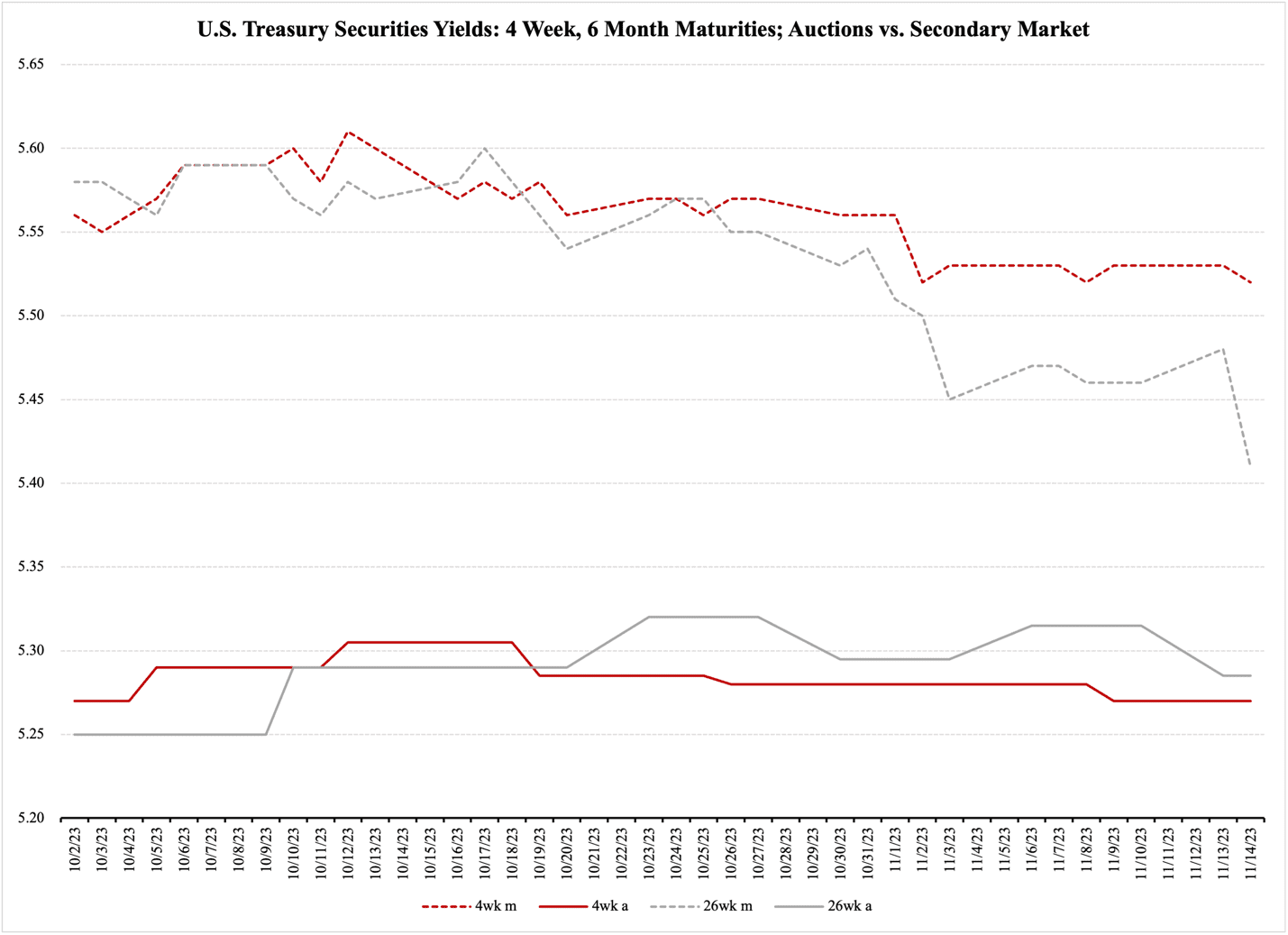

If the Federal Reserve keeps its interest rate unchanged, market rates will continue the gentle decline they began in October. As a sample, Figure 1 reports the yields on the 4-week (red) and the 6-month (gray) Treasury bills. The dashed lines represent yields in the secondary market, where investors can sell their bills before they expire. The solid lines represent yields at auctions where the U.S. Treasury sells new debt. Market rates began nudging downward in mid-October; as is commonly the case, auction yields are lagging a bit behind:

Figure 1

It is worth noting that as of Tuesday, November 14th, market yields had not responded negatively to the Moody’s report from November 10th. This shows that investors were expecting this, but also that they hope that Congress will respond constructively to the credit outlook change.

The slow decline in interest rates since mid-October cuts cut across the entire maturity spectrum, from one-month bills to 30-year bonds. Under the scenario where Congress creates a debt commission, this decline would continue, though not very far. There is a floor to how low the rates can go, and that floor is normally set by the Federal Reserve and its funds rate. If the Fed does not raise its rate in December, it will be a signal of marginally lower rates to come, a signal that will be welcomed by debt-market investors.

Overall, this scenario will preserve a somewhat tense stability in U.S. financial markets, but that stability will come at a price. Treasury yields will stay elevated over the winter and into the spring. Per Moody’s prediction, the 10-year note will yield 4.5% next year and 4% beyond that. With a debt commission in place, this forecast is marginally on the pessimistic side for 2024.

Under the contrasting scenario where Congress fails to create a debt commission, the FOMC chooses to raise its federal funds rate at its December meeting. Conventionally, the increase would be 0.25 percentage points, but it could be as little as 0.1 percentage points. Regardless of the size of the rate hike, the purpose behind it would be to signal that the Federal Reserve is worried about the complete lack of Congressional fiscal leadership.

As mentioned, this rate hike—if it comes—would have little if anything to do with inflation. It would be motivated by the growing threat of a fiscal crisis, and as such, a first for the Federal Reserve. This shift in policy motivation would send two signals to investors:

The last point is crucial: again, Moody’s explains its negative outlook on the U.S. government’s creditworthiness with the real risk that the dollar will lose its status as the global reserve currency.

Under this scenario, interest rates in the secondary market—the dashed lines in Figure 1—would quickly creep upward. Auction rates would follow right behind them, forcing the Treasury to pay more for new debt. For this reason, the Fed’s rate hike will be met with considerable political pushback.

All in all, the scenario where there is no response from Congress and a rate hike by the Fed would open up a completely new episode in American politics and the American economy. We have good reasons to worry about how Congress and the president would handle the crisis it would lead to; the experience from countries that have been through these episodes is not exactly a source of hope.