It has become fashionable among so-called ‘freedom conservatives’ to attack us national conservatives. Back in September, I delineated between this new strain of conservatism and the one I support, namely national conservatism.

Since then, the freedom conservatives have continued to show a need to attack national conservatism. Apparently, since we are taking flak, we are over the target; national conservatism has substance to offer, and the FreeCon movement is acknowledging the solidity of our ideas by focusing their criticism on us.

We from the national conservative camp are always interested in dialogue with anyone and everyone. We also value substance over rhetoric, which brings us to the latest FreeCon attempt on us. It comes from Steve Moore, an economist who splits his time between FreedomWorks and the Heritage Foundation.

On November 13th, Moore opined in the Washington Times that we national conservatives are more or less indistinguishable from the radical left. He also explained, creatively, that we are unfairly talking down the American economy—a character trait we apparently share with the left. But, he said, we national conservatives take our argument

a step further and maintain that this squeeze on the middle class, blue-collar Americans predates “Bidenomics” and America has experienced a 40-year secular decline that entails disappearing factories, income inequality, the decline of union power and shrinking wages.

In case it wasn’t spelled out in Moore’s op-ed, this is meant as an attack on national conservatism for being aligned with the left. It is easy to get confused reading his op-ed since Moore does not offer any quotes of any national conservatives making these points. The closest he gets is to refer in the next paragraph to two Republican U.S. Senators, Marco Rubio of Florida and J.D. Vance of Ohio. According to Moore, they have “dabbed in this movement.”

Continuing to proclaim what national conservatism is all about, Moore tells us that we:

want more restraints on “big business” (such as through antitrust enforcement and price controls), more protectionist trade policies, tax policies that provide credits and deductions for having more children, restrictions on legal immigration, and even higher taxes on the right. They are seeking a more activist role of government for the supposed failures of the free market.

At this point in Moore’s article, it is difficult to tell whether or not he pins all these opinions on Senators Rubio and Vance, or national conservatives in general. But just for the sake of the argument, let us put the rhetorical precision scalpel aside for a moment and take a look at Moore’s list of all things national conservative that he does not like. It gives us an idea of what he thinks national conservatism is all about—but also, perhaps inadvertently, a glimpse of what the FreeCon camp wants.

Here are the key points that Steve Moore wants to hang around our necks:

Enforcement of antitrust legislation. America has laws against undue industrial monopolization, dating back to the Sherman Act of 1890. By criticizing us for liking the enforcement of antitrust laws, Moore gives away that he wants to let corporations pursue profits even if it means complete monopolization of every market. As I pointed out back in September, as well as in June last year, capitalism is a superior economic system, but it also needs moral sideboards, or else it becomes its own worst enemy. Enforcement of antitrust legislation is one of those sideboards.

Price controls and higher taxes on the rich. Quite frankly, on these points, Steve Moore is more than welcome to present examples of when national conservatives have advocated them.

Protectionist trade policies. This is an idea that President Trump put to work. It has its origin in the fact that China has a well-earned reputation for using currency manipulation and other means to promote its exports and discourage imports. Simply put: you cannot have free trade with a country that does not engage in free trade. I am surprised that Steve Moore disagrees with us on this point.

Pro-family tax policies. This is indeed an idea that national conservatives embrace. It has been put to work successfully in Hungary, and it would be nice to see more of it in the U.S. federal tax code. I doubt that Steve Moore and the FreeCons are opposed to encouraging people to get married and have lots of kids; they likely oppose this idea because they want to do away with the federal income tax altogether. Part II of this article will discuss that idea in more detail.

Restrictions on legal immigration. As a legal immigrant turned American citizen, I wholeheartedly support such restrictions. Anyone with love for his country should do the same. By the way, Moore criticizes us national conservatives for wanting restrictions on immigration, while at the same time criticizing President Biden for having left the southern border “out of control.”

Moore then goes on to take issue with the points that some national conservatives have made about the economic struggle of America’s middle class. Moore disagrees with the notion “that middle-class America has fallen behind over the last 40 years.” He also accuses us of erroneously believing that “all of the economic gains have gone to the richest Americans” over that period of time.

Moore then goes on to take issue with the points that some national conservatives have made about the economic struggle of America’s middle class. Moore disagrees with the notion “that middle-class America has fallen behind over the last 40 years.” He also accuses us of erroneously believing that “all of the economic gains have gone to the richest Americans” over that period of time.

To prove that we are wrong and that the American economy is in great shape, Moore offers the following numbers:

Yearly median family income reached $78,000 in 2020, which is $20,000 higher than it was in 1983. That’s about a 35% after-inflation increase over the period.

Since Moore does not provide a source for his numbers, I will simply assume that he used the Census Bureau. Table A-4a from their income-and-poverty database shows a 39.1% inflation-adjusted increase in median household income over the period Moore refers to. If we stretch out the period to 2022, the increase is only 35.1% over 1983.

But let us not belabor details. The real point that Moore is trying to make here is that all households in America, regardless of income, have done very well over the past 40 years. To drive home this point, he pulls a statistical stunt that I have not seen before: he refers to the median income for all Americans.

This is like standing still to prove you can walk.

From an ideological viewpoint, Steve Moore is correct: income inequality is not a matter for government policy. As I will explain in detail in Part II of this article, we can and we must redesign the welfare state, both in America and in Europe, so that its purpose is no longer to reduce income inequality (a term I have examined in the past). However, this is not the point Steve Moore is making: he is trying to prove that income inequality has not gotten worse over the past 40 years.

And he does it by using only one household income statistic. Normally, when we want to show differences, we compare at least two numbers over a period of time.

The problem for Steve Moore is that income differences have in fact grown, and that we cannot completely ignore this. From a practical policy viewpoint, it does matter whether or not income stratification increases or decreases.

Here is the problem. If our economy only, or even primarily, benefits the wealthiest among us, we will inevitably create social tensions. Those tensions will sooner or later erupt, especially if those who are not experiencing much economic gain believe that they are being ‘left behind’ because the wealthy are doing better. That is almost never the case in real life, but history has unfortunately proven that the very perception of this causal relationship behind income stratification can easily become political dynamite.

A capitalist economy with proper moral sideboards is the best guarantee that nobody is ‘left behind’ economically. The question we should be discussing is what those sideboards should look like—and what they do not look like. To the latter point, we do not expect the capitalist system to elevate everyone apace; an organic free-market economy neither can nor should guarantee such growth patterns in personal income.

What matters is instead that our capitalist system elevates everyone at a rate where they can be satisfied with, ideally even proud of, their annual economic progress—regardless of how much better their neighbor is doing.

In short, national conservatives are worried about income stratification for two reasons:

The former point criticizes ‘anarcho-capitalism,’ a term that was popular among hard-core libertarians back in the 1980s and 1990s.

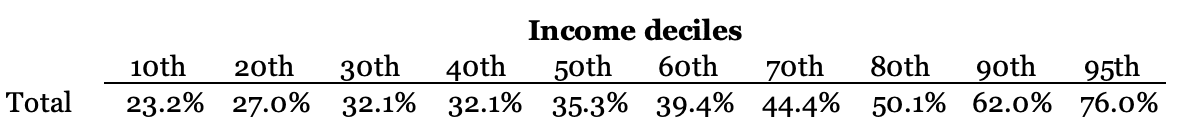

The latter point is actually relevant to the U.S. economy today. As it happens, Steve Moore is wrong about income progress for American households since 1983 (the year that Moore randomly picked in his op-ed). Based on the aforementioned Census table, we find major differences between lower- and upper-income groups. Table 1 reports the total inflation-adjusted gain in income from 1983 to 2022; it is worth noting that the 62% income gain of the wealthiest decile, the 90th, was almost 2.7 times bigger than the 23.2% for the poorest decile:

Table 1

Source of raw data: Census Bureau

In other words, it is indeed fair to make the point that not all American households have benefited the same from the economy over the past 40 years.

Steve Moore spells out in his op-ed that there has been no shift for the worse in the progress of household income. In response to this point, let us divide the period 1983-2022 into two, one from the start to the turn of the millennium and one from that time to today:

Personal income generally follows closely with the ups and downs in GDP.

Going back to our income deciles, we find a startling shift in income growth. To take four examples. Of their total income increases from 1983 to 2022,

In short, the poorest among us have seen virtually no income progress since the turn of the millennium. The wealthiest, on the other hand, have experienced strong continuity in their income growth.

There is one exception: the Trump economy. If we count it as 2017, 2018, and 2019, i.e., if we disregard the artificial economic shutdown in 2020, we find that real income for the 10th decile increased by 3.9% per year. Compare this to the 0.1% average annual income growth they have seen generally since 2000.

For comparison, this very same income group, the poorest decile, experienced an inflation-adjusted 1.3% income growth per year in 1983-1999.

Their real earnings grew 13 times faster back then.

If these numbers tell us anything, it is that the U.S. economy has been suffering systemic ailments over the past two decades. I am surprised to see Steve Moore deny this.

If we conservatives want to be relevant in America, we simply have to recognize that:

a) The American economy suffers from systemic ailments that have visibly weighed down the growth of household income since the turn of the millennium; and

b) These ailments correlate painfully with growing income stratification, which very likely means that the ailments are to blame for the virtually non-existent advance in income for the poorest among us.

In Part II, I will discuss in depth what the systemic ailments are, and what we conservatives can do about them. I will do this while clarifying the national conservative position—and how it differs from the viewpoints put forward by freedom conservatives.

My goal is not to widen the divisions, but to persuade freedom conservatives to cross the line and join us.

We have better ideas—and better cookies.