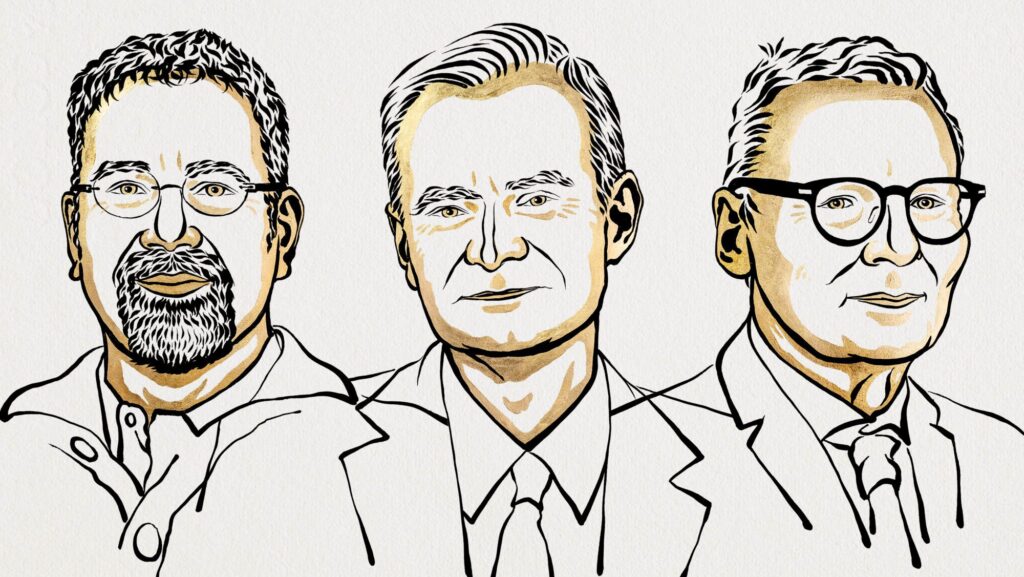

Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James A. Robinson

Image: Niklas Elmehed © Nobel Prize Outreach Person/Organization (Laureate):

The Swedish committee for the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics has announced new laureates. Three American economists win the prize for allegedly proving that colonialism 500 years ago still holds some colonized countries in a grip of poverty and economic stagnation.

Will anyone be surprised if I say that the research rewarded by the committee is empirically weak and methodologically questionable? Probably not. But what is even more troubling is that the prize committee itself opens its statement explaining this year’s choice of laureates with an unabashedly political postulate:

The poorest 50 percent of the global population earns less than a tenth of total income and owns just 2 percent of total wealth. This inequality is primarily driven by disparities between countries, which contribute to approximately two thirds of global income inequality.

In other words, the three economists Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James A. Robinson are awarded this year’s Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics because their research explains why there is “income inequality” in the world. They are not awarded the prize because they have made significant scholarly contributions to the science of economics.

The four members of the economics prize committee will adamantly disagree with me here. Their long and admittedly well-written motivation for why Acemoglu et al. get the prize goes to great lengths to provide a scientific backup for the prize. However, as I will explain below, their efforts in this regard are stretched so thin that they become transparent.

Before I delve into this year’s prize, a quick reminder that this year’s blatantly political Nobel Memorial Prize comes as no surprise. In recent years, the prize committee has made a habit of turning its laureate choices into ideological statements. Last year they gave the prize to Claudia Goldin for having dispensed Marxist feminism under the guise of ‘economic science.’

The year before, the prize was handed out on highly questionable scholarly grounds, and the politics of it was somewhat convoluted. However, the fact that former Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke got it, after having monetized the U.S. government’s budget deficits and laid the groundwork for the highest inflation in 40 years, is reason enough to raise concerns regarding the integrity of the economics prize.

It certainly does not help when, as I explained back in June, 16 Nobel Memorial economics laureates enter the presidential campaign “as political errand runners for the incumbent president,” flaunting their Nobel memorial medals as some sort of badge of reputability.

As the aforementioned quote from this year’s prize motivation showed, the Nobel memorial economics committee continues to spread the political contamination of the prize itself. Although the research done by this year’s laureates is in itself interesting, it certainly does not rise to the standards of such prominent economics laureates as Paul Samuelson, Vassily Leontief, Milton Friedman, James Tobin, or Tryggve Haavelmo.

For the sake of fairness, let me begin by recognizing the respectable, even to some degree impressive work by Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James A. Robinson. It consists of the development of a methodology for defining and tracking economic and political institutions over time. An institution in this context is a structure of laws, regulations, rules, habits, or similar formalized human behavior that sets a framework for economic activity.

The property right is a commonly quoted example: by regulating the terms on which someone can own an asset, the institution of the property allows property owners to use their assets in predictable ways. Land can be used for agriculture; a house can be used as a workshop or a store; money can be loaned out for productive projects.

Studying the evolution of economic and political institutions in countries colonized by Europeans, Acemoglu et al. conclude that some colonized countries have become prosperous because the Europeans allowed them to. Those that became prosperous did so because the institutions that the colonizers created benefited everyone; by contrast, former colonies that are now poor were given institutions that solely benefited the Europeans.

There are several methodological flaws in the studies produced by the laureate trio; most notably, they do not distinguish between the institutional traditions from which the European colonizers came. Instead, they lump together German, Portuguese, French, Italian, and British efforts in their overseas territories. We do not have to delve very deeply into history to realize what a major error lies in this; it should suffice to do a brief review of the forms of government, the historic status of individual rights, and the levels of economic and individual freedom in these countries.

Although some of the contributions by the laureates differentiate between pathways of institutional development, those pathways are not conditioned on traditions that originate in the colonizing countries.

Another methodological flaw is the lack of analysis of factors outside the institutions. In the case of the United States of America, the British colonial institutions strongly opposed the formation of an independent government based on Enlightenment values. If anything, the tremendous economic success of the United States over the past 250 years is a refutation of the case that the three Nobel Memorial laureates try to make.

With all this said, there is one overarching methodological flaw that I find particularly hard to disregard. While the laureates want to study the role of institutions in shaping the economic evolution of a country, they narrow their focus to former European colonies around the world. In doing so, they disregard Europe itself, the most obvious—and for economists most attractive—full-scale laboratory for comparative institutional research.

Perhaps the most low-hanging fruit here is Germany. After having been united in the 19th century and functioning as one country until the end of World War II, the country was split into two parts with institutional structures of very different quality.

If this year’s economics laureates had wanted to toss out all other factors that risk complicating their empirical research, they could have made the two Germanys the core of their study. From there, they could have sprawled out and included other former Warsaw Pact members and compared their institutional structure before, during, and after the Cold War, to the corresponding structures in Western countries. These two institutional traditions—for lack of a better term—could then easily have been related to the economic evolution of these countries.

By instead taking the route through colonization, the three economics laureates have implied—not very subtly—that poverty around the world is the fault of the Europeans who traveled the world to establish colonies 500 years ago.

This focus explains why the economics prize committee was drawn to this body of research. Their own agenda, spelled out above as a deep lamentation of international economic differences, is thereby confirmed and reinforced by the research they have rewarded.

One question remains: why is the Swedish committee for the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics so politically invested in the reduction of “income inequality” around the world? The only rational explanation is that the chairman of the committee, Jakob Svensson, has devoted his career to research on poor, developing countries—with a particular affinity for Uganda.

It is not far-fetched to suggest that Svensson’s own research is morally motivated: he simply does not like the fact that there are poor countries in the world. That is a totally respectable position to take, and—frankly—one that most of us can subscribe to. At the same time, such personal moral preferences have no place in work that is aimed at rewarding substantial contributions to the science of economics.

I have long criticized the concept of a Nobel-style prize in economics. Mostly, my criticism has been based in the field of theory of science: as a social science, economics is by its very nature an open discipline influenced by human moral considerations. Therefore, it is an inherently flawed project to award a prize on the same terms as one does in closed-system natural sciences.

Recently, though, my criticism has been reinforced by what seems to be a deepening political contamination of the prize. This year’s and last year’s prizes are cases in point. They are particularly concerning given what has happened to the (real) Nobel Prizes in Peace and Literature. There, we have seen highly problematic examples of politicized laureate picking.

Eventually, a rising degree of politicized decision-making in the selection of economics laureates can detrimentally affect the status of the (real) prizes in, e.g., Physics. I hope that the Nobel Foundation takes this threat seriously enough to either have a long talk with the Economics Prize committee—or, preferably, simply sever its ties with the prize.