The recent turmoil on the world’s leading stock markets caused widespread speculation about a pending economic disaster. In the three weeks from July 16th to August 6th, the S&P 500 index of the New York Stock Exchange lost 7.5% of its value. Parallels to the notorious crash of 1929 have flown back and forth across the internet, as they always do when there is a sudden downward movement in the stock market.

Some commentators have perceived the situation as so bad that they want the Federal Reserve to make an emergency rate cut, i.e., not wait until its next scheduled meeting in September.

I have good news for everyone who has been panicking: you can breathe again. There will not be a big economic crash—i.e., a depression. There will be a recession, but unless some government somewhere decides to do something really, really stupid, we are not going to be hurled into an economic depression.

By “really, really stupid” I mean three things:

If our governments in North America, Europe, Japan, and other major economies can avoid doing any of these three things, then all we will have is a recession for 12-18 months and then the economy will start rebounding again. There is a caveat here: Europe is going to experience a more protracted recession with a weaker recovery on the back end, while the United States likely will see a brief, two-quarter slowdown in GDP growth to zero, after which the economic wheels will start spinning again.

The plummeting stock-market values do not indicate that the coming recession will be particularly bad. These things happen, with different variables interacting in different sequences; this time around, there was an interaction between pessimistic U.S. economic data, an unusual interest-rate hike in Japan, and major shareholder sales on both the American and Japanese stock markets.

The point that causes confusion among analysts is that the stock sell-off—which as mentioned has stretched out over three weeks—is nowhere near proportionate to the moderately negative economic news that is being blamed as the original cause. An uptick in U.S. unemployment by 0.1 or 0.2 percentage points does not constitute a reason to panic sell stocks, especially since—as I explained on July 26th—other data for some time now has pointed in the same direction.

To be fair, things can happen quickly if investors, portfolio managers, and analysts come to work one day and are met by a slew of data that, taken in isolation, are not much to worry about but, when compounded, paint a grim picture. But even this approach fails to explain the massive sell-off, especially with U.S. economic data being an important part of the picture. The fact that the Japanese central bank raised its interest rate for the first time in 17 years is, of course, noteworthy, but level-headed people who are responsible for billions of dollars of other people’s money do not go into panic mode even at such an unusual event.

It is also worth noting that the interest-rate hike was small, 0.25 percentage points, and that the Japanese stock market initially responded positively to the rate hike itself.

To make a long story short, the stock-market plunge is an exaggerated reaction to economic news that is negative but nowhere near panic-inducing. But does that mean there was no justification whatsoever for the big stock-market adjustment?

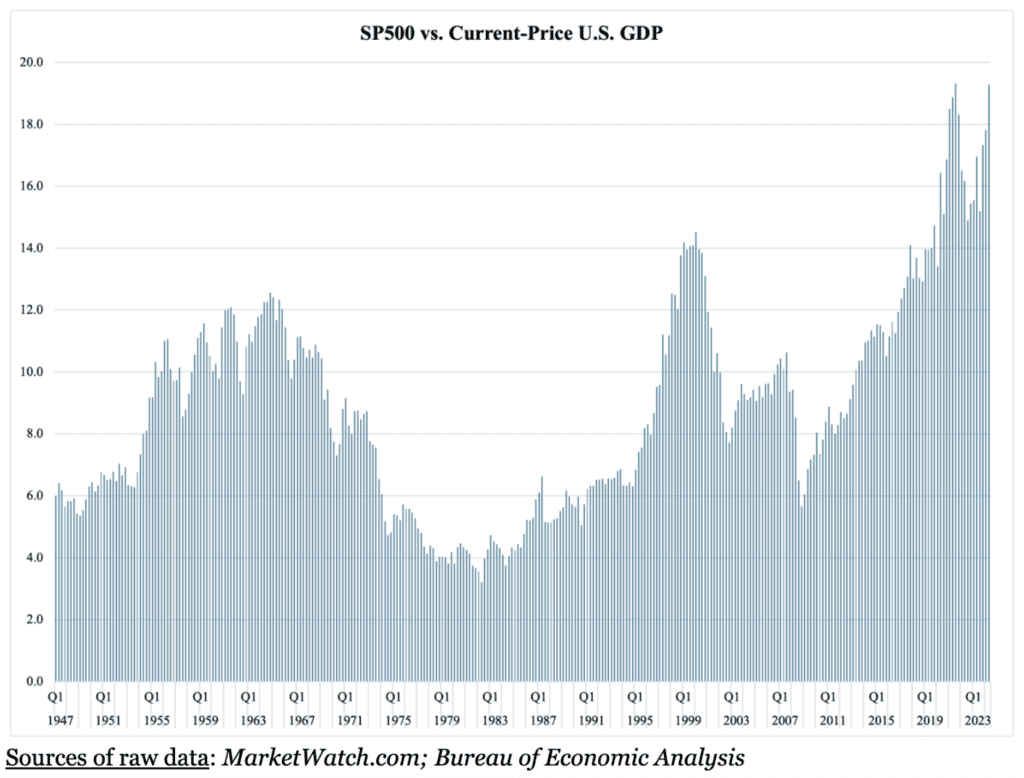

No, that would be the wrong conclusion. There was indeed a reason for a major downward adjustment on our stock markets. Taken generally, stocks are massively over-valued, not just in America, and they have been so for a long time. Figure 1 exemplifies with the U.S. stock market’s S&P500 index. The index value represents the weighted prices of all the stocks included in the index, which means that when the index rises, we witness a rise in the prices—values—of the stocks.

The S&P500 index is currently ‘valued’ around in the 5,000-5,500 range. These numbers do not mean anything in themselves, but when we compare them to the same index 10, 30, or 50 years ago, we get a good idea of how the total value of the stocks in the index has evolved.

Stock values are founded in the performance and, ultimately, profitability, of a corporation. The performance is illustrated by the value and the trends in production; since GDP is the broadest possible measure of economic production that we have, we can use it as a proxy for the total production of all the corporations included in the S&P500 index.

We now have a ratio: the index number to GDP. For simplicity, in Figure 1, this ratio is multiplied by 100 (or else we would operate only with fractions). A sound stock market would, over time, value its stocks in a constant ratio to the production value, i.e., GDP. In other words, in Figure 1 we should see the columns remain about the same height over time.

That is not the case:

Figure 1

In the 1950s, the stocks under the S&P500 increased in value faster than the U.S. GDP did. This was corrected for by the stock market in the 1960s and 1970s. After a period of calm in the 1980s, a protracted but volatile trend began where stock values outperformed GDP. In other words, a gap opened up between market stock values and the economically defensible value that would evolve on par with GDP.

The value gap has grown with particular ferocity since 2007. Today, it represents 47.6% of the total value of the S&P500, which means that out of every $100 that the stocks in the index are worth according to the stock market, $47.60 has no foundation in economic performance.

It is important to remember that this value gap varies significantly between stocks; my number is an aggregate that applies to the entire ‘portfolio’ of S&P500 stocks. But given that we accept GDP as the final arbiter of the S&P500’s real value, there are two compelling pieces of information embedded in this value gap:

When viewed from this perspective, the stock-market value plunges in the last couple of weeks take on a new meaning: investors who are aware of the significant speculative value in the stocks they hold suddenly became afraid that he hot air that fuels speculation would stop flowing into the stock market. They decided to adjust their portfolios by selling off stocks that they perceived as having been the most inflated by speculation.

In conclusion: fear not the stock market drama; fear politicians who use it as a pretext to do stupid things to the economy. With that said, though, Figure 1 explains why we need a long period of slowly declining stock-market values. That would suck the speculative air out of the market and restore long-term solidity as the foundation for pricing and trading corporate shares.