Two years ago, Ulf Kristersson led a center-right coalition to a narrow victory in the Swedish national elections. Referred to as the ‘Tidö coalition’ after the old castle where they negotiated their election platform, the four parties have thus far made reasonable progress toward delivering on their promises. Substantive reforms to immigration policy have slowed immigration, though the government’s claim of achieving net outbound migration are a bit premature. Energy policy now includes a return to nuclear power; and a reform to the fuel tax—a contentious issue in the 2022 election campaign—has delivered markedly lower prices at the pump.

Halfway to the 2026 election, Kristersson’s government has now turned its focus to economic policy. The government budget for the 2025 fiscal year offers several adjustments to the tax code, with the aim to stimulate economic growth.

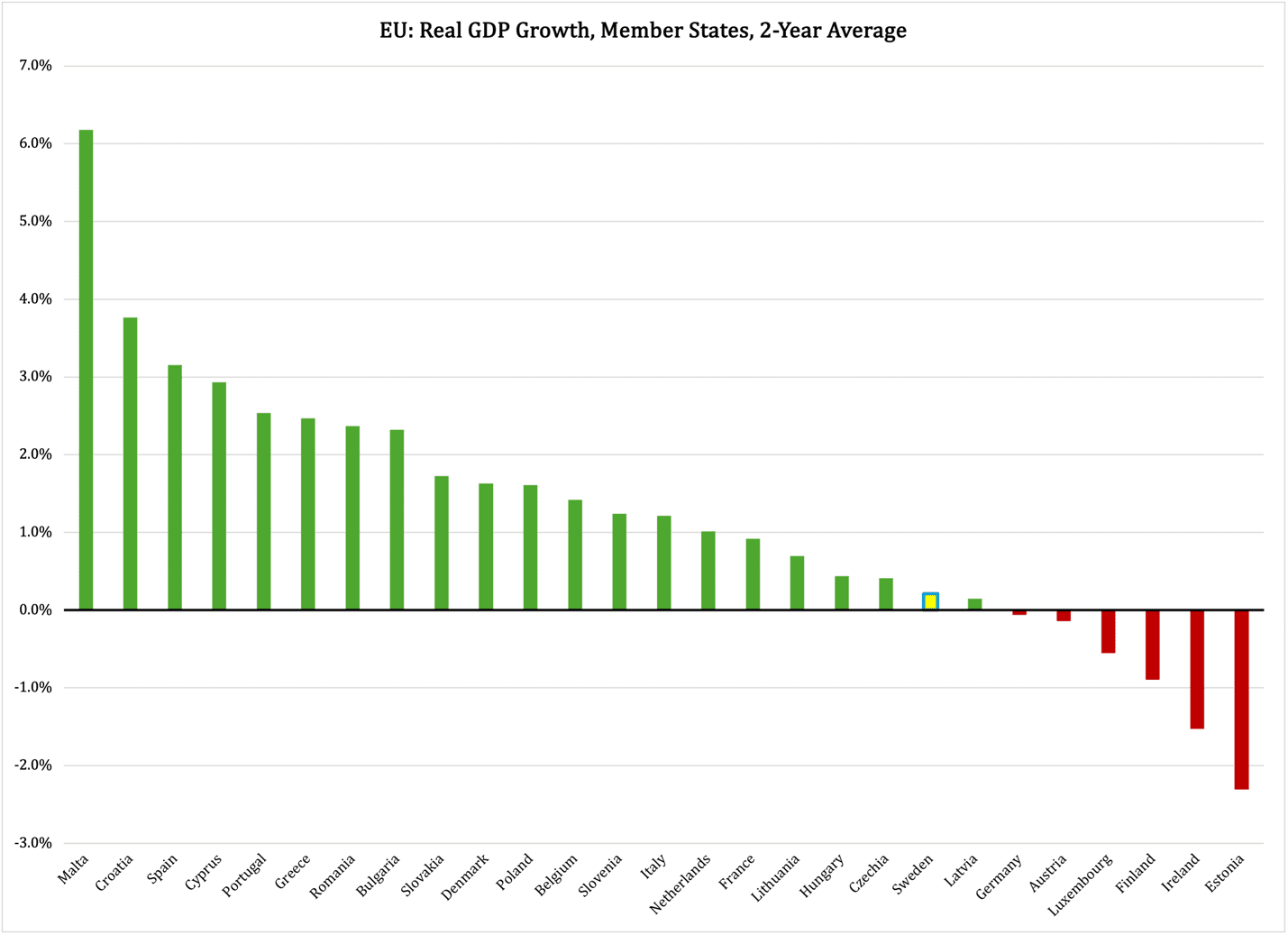

To call it a ‘tax reform’ would be too generous, but the Kristersson government’s ambition behind the tax adjustments is good. The Swedish economy is in poor shape, as explained by the tiny yellow column in Figure 1, which reports the average real annual growth rate in all EU member states over the past two years:

Figure 1

When the Swedish parliament, the Riksdag, recently debated the government’s budget, the left-wing opposition tried to capitalize on the slow growth rate by accusing the Kristersson government of being responsible for it. Statistically, it looks like there is some merit to this criticism: the Swedish GDP managed to grow by an average of 0.2% per year over the past two years, but over the past year the average is -0.1%.

In other words, it looks like the democratic-socialist opposition in Sweden has a point. However, if we examine when the growth in Figure 1 actually happened, it turns out that two-thirds, i.e., 18 of 27 EU member states had a lower GDP growth rate in the past year than they did in the previous year.

Plain and simple, when the social democrat party’s budget spokesperson in the Riksdag debate, Mikael Damberg, claimed that the economy is improving in every other country in Europe, he was simply painting a false picture for the viewers. The simple truth is that economic activity is slowing down in most European countries, and Sweden is part of that trend.

That does not mean Kristersson and his center-right coalition get off the hook. On the contrary, they were slow in taking seriously the deteriorating state of the Swedish economy; the paltry growth rate is now accompanied by Europe’s third-highest unemployment rate, both in total and among young workers.

The budget for the 2025 fiscal year is supposed to compensate for this lack of attention. In order to focus the budget on growth-generating fiscal measures, the Kristersson coalition decided to rely heavily on basic economic theory to explain a series of measures that (mildly but still) reduce the tax burden on the Swedish economy.

In the budget debate, Sweden Democrat economic spokesman Oscar Sjöstedt stated firmly that the one instrument the government has at its disposal to stimulate growth is to cut taxes and make gainful employment financially relatively more attractive than unemployment. To be frank, this is a crude and overly simplistic theory of economic growth, and it is not even a comprehensive explanation of what generates growth.

At the risk of disappointing a number of conservatives, I need to state the facts: Say’s law is false: supply does not create its own demand. Anyone who wants to prove me wrong is welcome to ship 1,000 brand-new Bentleys to Iceland and call me when they have all been sold at a profit.

In the real world, the economy is demand-driven. In healthy, advanced economies, consumer spending is the largest domestic activity, followed by private sector capital formation. The former leads to the latter: when consumers have money to spend, businesses invest in new facilities and new workers to meet that demand.

On this point, Damberg, the social democrat, got it right during the budget debate. However, that does not mean Sjöstedt was wrong: somewhere along the chain of economic activities, the economy needs a sufficiently large workforce to meet all the needs and wants that households and businesses have. For that purpose, the primary economic instrument at the hands of a government is tax policy.

Which brings us to the pig’s breakfast that ended up being served to the Swedish workforce in the 2020 fiscal year government budget. While Sjöstedt did a commendable job explaining both the nature and the virtues of the tax cuts, he and finance minister Elisabeth Svantesson with the Moderate Party carefully avoided any mention of the significant downside of their proposed tax cuts.

Politically, it is understandable—even expected—that a politician tries to promote his party’s policies in the best possible terms. But when the upsides are barely strong enough to outweigh the downsides, stubbornly emphasizing the former while turning a blind eye to the latter does not exactly inspire confidence.

Here is the problem. Superficially, the Swedish income tax code is relatively benign to taxpayers. Most taxpayers only pay a flat, combined local and regional income tax, usually in the 30-35% bracket (the exact rate depends on where you live). Those who make enough to qualify for the supplementary national income tax have to fork over another 20% of their income above a certain threshold.

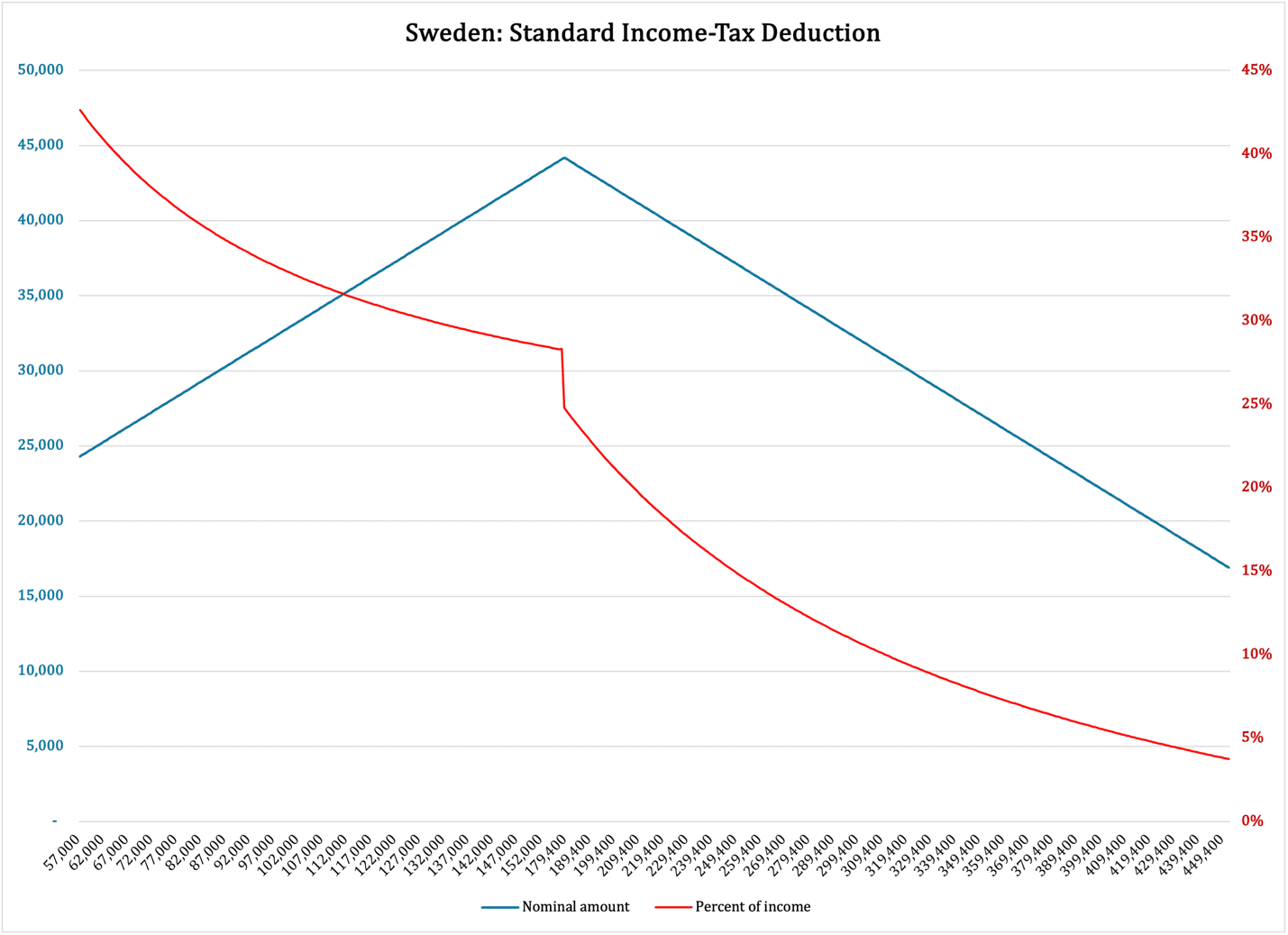

This design of the tax code is a good platform to work from if you are a politician who wants to see more people join the workforce. The problem is that the tax code has a lot more in it than just the aforementioned tax rates. To start with, there is a standard deduction, but it does not work like it does in America, where you simply subtract a fixed amount from your taxable income regardless of how much you make.

While the tax brackets look simple enough, the standard deduction—and other deductions—suddenly makes the tax code a lot more complicated. In place of a simple, equal-for-all amount of money, the Swedish standard deduction varies with your income. The variation is not even linear: as illustrated by the blue line in Figure 2, the amount one can deduct under the standard deduction feature increases early on as you make more money. When it reaches a breaking point, the amount starts to fall.

The red function explains the same thing, but as a percentage of the taxpayer’s income:

Figure 2

The gradual loss of the standard deduction has the nasty, unintended effect of imposing a marginal tax on the taxpayer’s rising income. As a result of the ‘pyramid’ that is the blue function in Figure 2, once the income earner gets on the far side of the top, the income he must pay in taxes suddenly accelerates at frightening speed.

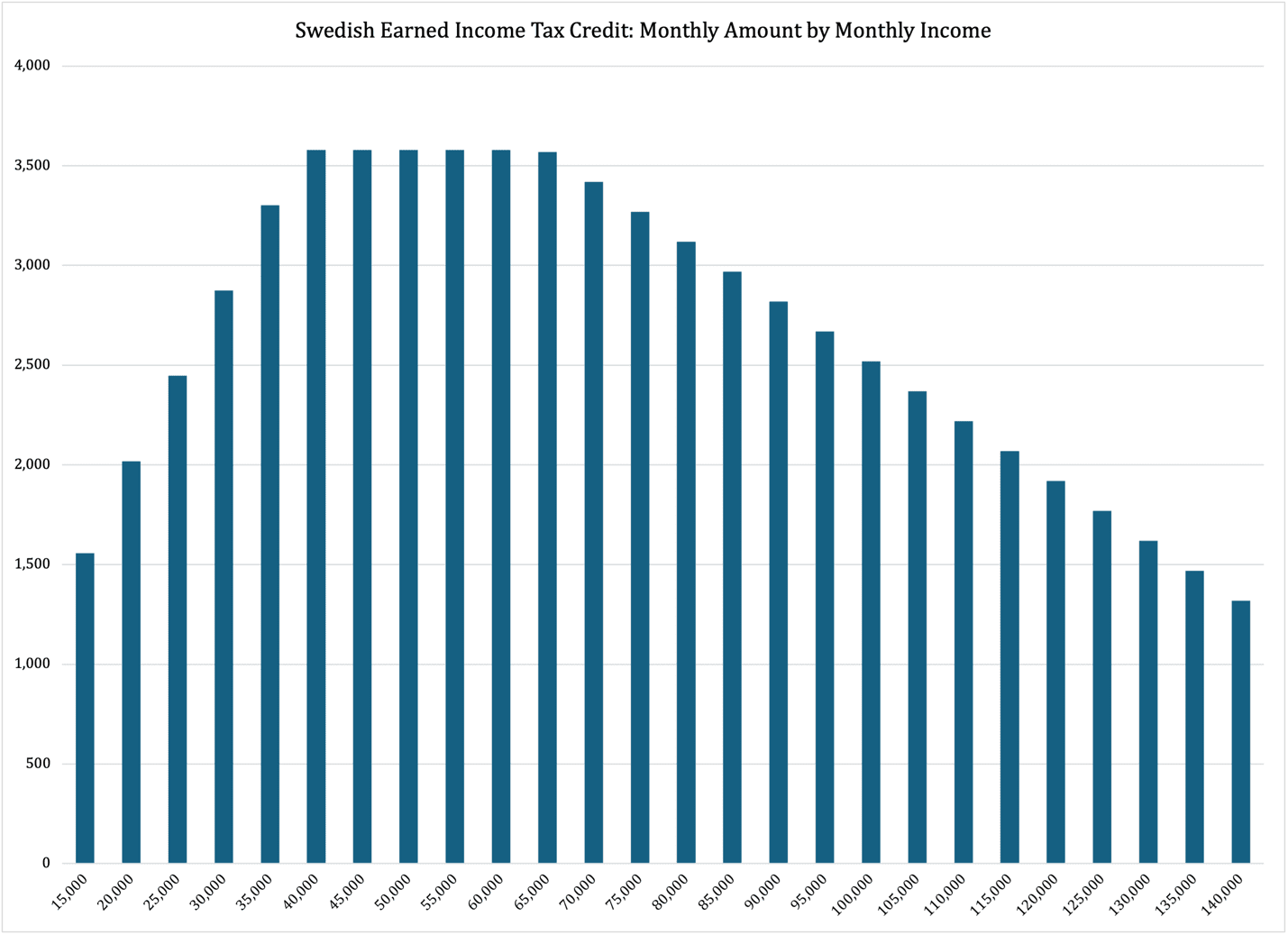

For reasons that can only be found in the pile of intellectual misfires, back in its term in office from 2006-2010, the center-right government under Prime Minister Reinfeldt created a Swedish version of the American Earned Income Tax Credit. As Figure 3 shows, this tax deduction has the same effect on the taxes owed: first, the credit expands quickly, then it turns nominally flat as income grows, followed by a third phase where the tax credit declines.

Figure 3; 1,000 SEK equal approximately €88

The combination of the earned income tax credit and the loss of the standard deduction add up to a clearly noticeable marginal tax effect. Together with other features of the tax code (the payroll tax and minor, miscellaneous adjustments), the standard and earned-income deductions impose a significant marginal income tax on Swedish income earners:

At some point, this marginal effect on a person’s efforts to make more money will backfire. By using the earned income credit to encourage people to do just that, the incumbent center-right government actually throws hurdles in front of itself by reinforcing the high marginal tax effects illustrated here.

It is possible that the tax credit adjustments included in the Kristersson government’s budget will, on the margin, increase labor supply at the lowest income end of the workforce. But given that they simultaneously increase the marginal tax effects that discourage people from working more, they squander a significant opportunity to genuinely make more work more attractive.

Could the Kristersson government have done anything differently? Yes, they could indeed have made better choices. Next week, we will take a look at a couple of alternatives.