Europeans commonly believe that America does not have a welfare state. Many American conservatives share that belief, and those who do recognize that we have one, firmly believe that it is not socialist.

They are all wrong: America has a big welfare state, and it is distinctly socialist in nature. It is based on the very same ideology that underpins the Swedish welfare state.

Its foundation was laid by President Lyndon Johnson in 1964 with his so-called ‘war on poverty.’ Since then, almost every president has helped the welfare state grow.

Today, there are more similarities than differences between America’s and Europe’s welfare states. We in the U.S. do not yet have single-payer health care, and our income-security systems are not as sprawling as they are in Europe. However, the long list of social benefits that we do have operates on a socialist ideological basis: they elevate the standard of living of the gainfully employed with lower incomes, and have better-off citizens pay for it.

In everyday parlance, we call this ‘economic redistribution,’ which is used to fight ‘income inequality.’

More recently, much political effort has gone toward ending our successful private health care system. As of 2021, government programs pay for 49% of all health care in America, up from 45% in 2019 and 40% in 2008.

Government is also steadily increasing its presence in the pocketbooks of American families. Social benefits equal 10% of household income, almost double the 5.5% share from 20 years ago.

Currently, welfare state spending accounts for two thirds of the federal government’s budget. From 2000-2010, that share was about 60%. In the 1980s, it was just below 50%.

In the early 1960s, before Lyndon Johnson’s war on poverty, welfare-state spending was only 25% of the federal budget.

This is just spending by the federal government. States and local governments dole out about 40% as much as the federal government does; added together, in 2021, all these levels of government spent 35% of the U.S. economy.

This share is low compared to European countries where the share is usually in the 40-50% bracket. However, it is high for the American economy, and if the forecasts from the Office of Management and Budget are correct, this share will only continue to rise.

The exact pace at which government spending will continue to grow depends on how successful the American Left is at expanding the welfare state. They keep trying: every Democrat presidential candidate since at least Michael Dukakis in 1988 has expressed support, in one form or another, for a complete government takeover of health care. Proposals are aplenty for expanded tax-paid childcare and new income-security programs, including paid sick leave and paid family leave.

For the most part, Congress grows the welfare state by means of ‘mission creep:’ they relentlessly expand existing programs, small steps at a time. Many entitlement programs got major infusions of new money during the 2020 pandemic, and although some of that spending has expired, ‘pandemic relief’ spending reinforced the mission-creepy nature of the welfare state.

If Congress eventually manages to transform America into a Scandinavian welfare state, it would be bad not just for America, but for the world. The welfare state is more than a threat to the economy. When government usurps a monopoly on our children’s care and education, our health care, and financial security, it forces us to adjust our lives to the ideological dictates that define all these entitlement programs.

On the cost side, welfare-state taxes make it costly for a family to live on one income, forcing parents into a two-income life. As a result, they are forced to become dependent on government-provided benefits and to put their children in government-run daycare.

On the benefits side, we are at the mercy of tax-paid bureaucrats. In a government-run health care system, fiscal scrooges will decide what patients get what treatment, and when. Young patients are put ahead of middle-aged or elderly patients because the government estimates that once cured, young people will pay more in taxes over their remaining life span than older people will.

The latest fashion trend in government-run health care is to tell elderly patients that their lives are no longer worth the expense of medical services. Patients are offered euthanasia.

In Europe, it has become second nature to accept that lives are shaped by taxes and government spending to such a degree that it is not even considered unnatural.

Americans are not yet accustomed to this way of life. They maintain a higher degree of independence in their life choices, but the differences may soon be gone.

Would this be bad, though? Is not the reduction of income inequalities a noble goal to strive for?

It is tempting to answer these questions with a question: In which Korea would you rather live as poor—North or South? The north has eliminated all economic differences; the south allows them to flourish. In the north, individual citizens are banned from trying to improve their own economic conditions; in the south, they have opportunities to build a career, start a business, and determine the course of their own lives.

The ‘inequality’ questions are compelling in their suggestion that if we all conform to the life choices mandated or incentivized by the welfare state, everyone will be better off.

The problem is that this is not true: we are not better off by trying to reduce income differences. As the North-South Korean case tells us, egalitarian economies make everyone poor. One reason is that the welfare state is inherently unable to eliminate so-called income inequality.

As I explained in a recent analysis of the British welfare state, the more government tries to reduce income differences, the less successful it is. While the benefits for low-income families have become more and more generous, so-called income inequality in Britain has actually increased.

Yes: there are bigger differences in the standard of living in Britain today than there were 40 years ago, despite the fact that government has expanded its efforts to reduce those differences.

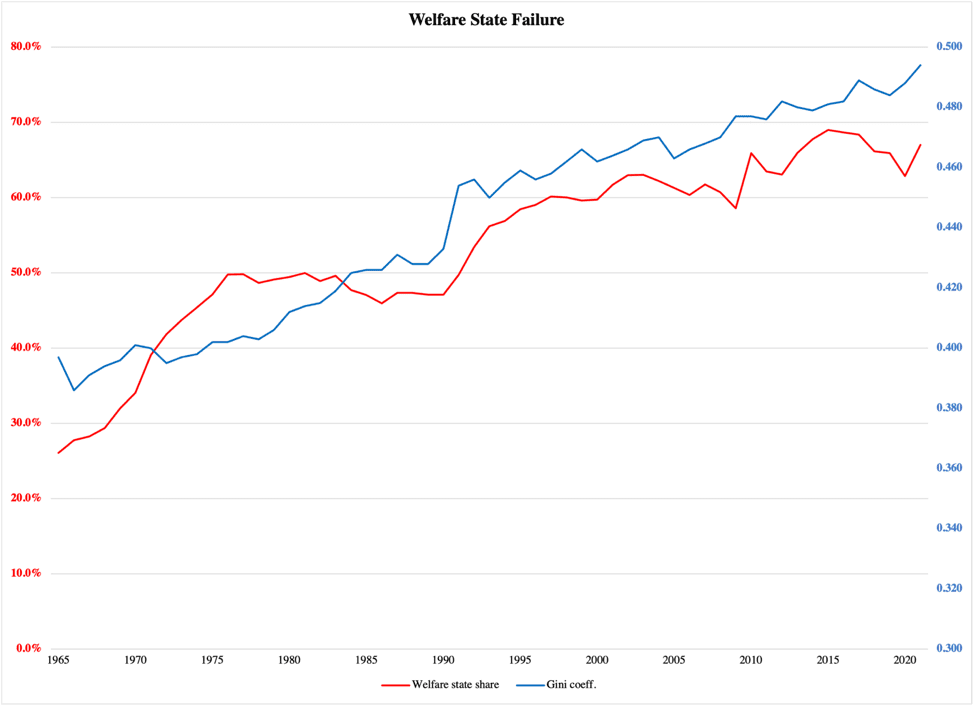

Although America does not have quite the machine of economic redistribution that Europeans have, our welfare state is still sadly inefficient. Figure 1 explains by comparing two sets of data:

The Gini coefficient measures income differences between individual citizens. The coefficient value is low when income differences, or inequalities, are small. In Figure 1, the Gini coefficient rises steadily, meaning that income differences in America have increased since the mid-1960s.

Remarkably, this has happened while the federal government has spent a larger and larger share of its money on reducing those very same differences:

Figure 1

Figure 1 is a damning verdict over half a century of American welfare-state spending. The more politicians try to reconfigure the distribution of income, the less they succeed.

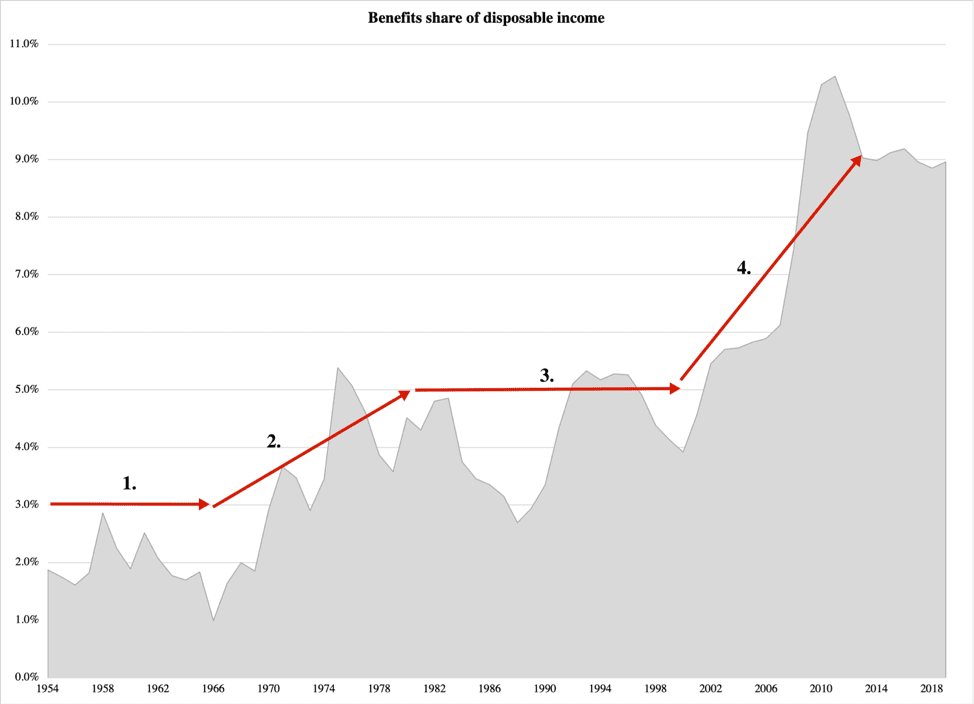

Figure 2 piles on, reporting the share of disposable income that consists of government benefits. In the 1950s and early 1960s, less than 2% of the money that America’s families had at their disposal, came in the form of government handouts. Most of it at that time was Social Security, i.e., retirement and disability benefits.

Then came 1964 and President Lyndon Johnson launched his infamous war on poverty. Let us break down the history of his socialist welfare state into the following phases:

Figure 2

In Phase 1, America had a welfare state, namely the socially conservative one founded under President Franklin Roosevelt. Government programs included Social Security and limited benefits for the poor.

In 1964, Congress created or vastly reconfigured a long list of programs. Benefits were no longer of a last-resort kind, but were made available to gainfully employed, low-income workers.

This was a paradigmatic shift in the role of government, a shift that I summarized in one question in my book The Rise of Big Government (p. 50): “When is government big enough?”

The entitlement-benefit share of disposable household income starts growing in Phase 2. The bulk of the expansion consists of two new health care programs: Medicare for retirees and Medicaid for low-income families.

Other presidents have added to the welfare state. The next big leap came in 1975, when Congress passed a new program for gainfully employed, low-income families. The ‘Earned Income Tax Credit,’ EITC, pays out cash benefits under the guise of refunding taxes paid. In reality, the EITC refunds exceed what most entitled workers pay in taxes, which makes it a traditional social-benefit entitlement program.

From the late 1970s through the mid-1990s (Phase 3), the welfare state made minor progress, with President Reagan signing laws that expanded Medicaid. Phase 4 begins when President Clinton signs SCHIP, a health care program for children, into law. It continues with two leaps in government-paid benefits for households. First, President Bush Jr. signed a massive expansion of Medicare, which brought with it significant growth in Medicaid. Then, in 2010, President Obama got Congress to pass his ‘Obamacare’ reform. It expanded government into the thick of the private health-insurance market, drastically altering pricing and benefits structures of health plans.

With benefits distributed based on household earnings, the program dedicatedly implements the socialist doctrine of economic redistribution.

Since the end of Phase 4 in 2010, the welfare state has been digesting its expansion, but that does not mean that America’s political elite has been resting on its laurels. Its latest tax reform, passed in 2017 under President Trump, solidified the federal income tax system as a tool for economic redistribution.

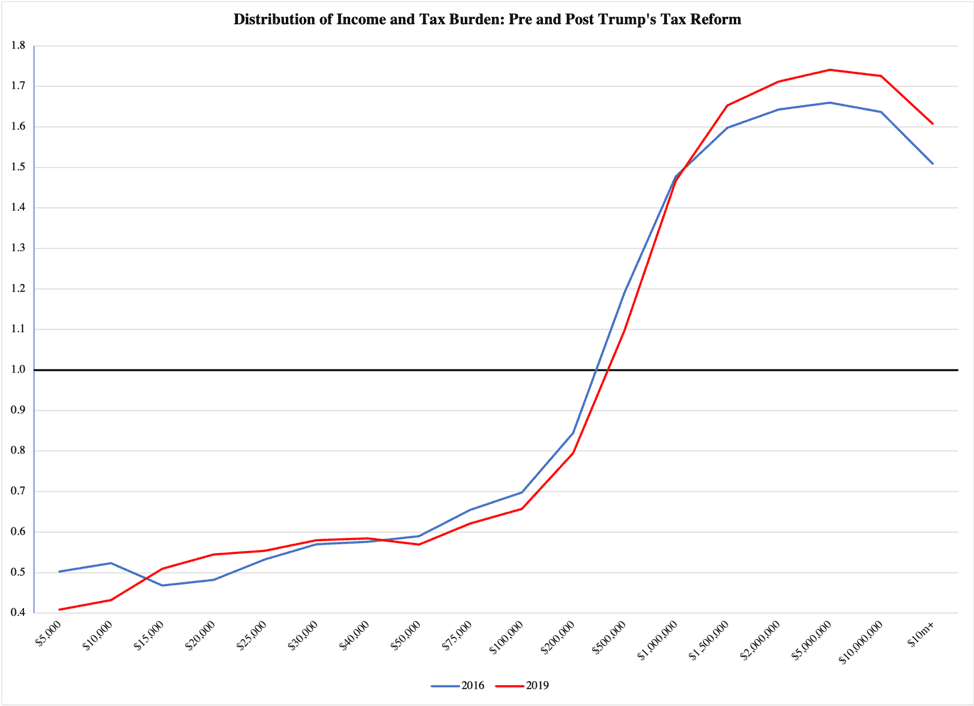

The federal income-tax system currently has seven brackets with rates ranging from 10% to 37%. Six percent of all taxpayers make more than $200,000 per year. In total, this group makes 48% of all taxable income, yet they pay 65% of all personal federal income taxes.

The often-vilified 1% top earners, the ones who make more than $500,000 per year, pay 43% of all personal federal income taxes, but they only make 28% of the taxable income.

By contrast, 72% of all taxpayers, who make less than $75,000 per year, earn 16% of all taxable income but only pay 9% of the taxes.

The ratios between these percentages tell us how much more, or less, taxpayers of different incomes pay in taxes. They should be:

Figure 3 reports these tax-share scores by income group. It also compares those numbers for 2019, two years after the Trump tax reform, with the same numbers for 2016, the year before his reform. Behold—the often-vilified Trump reform made the rich pay an even higher share of the federal taxes:

Figure 3

In conclusion, the American welfare state is highly socialist in nature. It faithfully benefits lower-income families and faithfully pays their benefits by taking almost all its taxes from those with higher incomes.

While doing this, the welfare state is also sordidly inefficient. It leaves the country worse off in terms of income differences than it would have been without any welfare state. Meanwhile, economic growth is sluggish and most household incomes are stagnant (except during the first three years of the Trump administration).

The American welfare state, like most of its European counterparts, has failed to deliver on its ideological promise. Perhaps it is time to rethink it and try some conservative ideas. Here are some, for starters.