Through the Church Year with Thomas Aquinas

The theology of St. Thomas Aquinas is suitable for leading today’s secular and increasingly godless world back to the salvation of the Gospel.

The theology of St. Thomas Aquinas is suitable for leading today’s secular and increasingly godless world back to the salvation of the Gospel.

Dante’s La Vita Nuova is indisputably the work of a young man, a man whose passions (and poetic compositions) are still discovering the place they ought to have in the world. Thankfully, though, Dante’s ‘immature’ juvenilia is far greater and more penetrating a work than most poets can ever compose in the entire course of their lives.

An apt but uncharitable description of Medea’s incongruities might paraphrase Woody Allen’s description of a monster as a being with the body of a crab and the head of a social worker to say that Cherubini’s work sounds like a Mozart opera with a Beethoven overture.

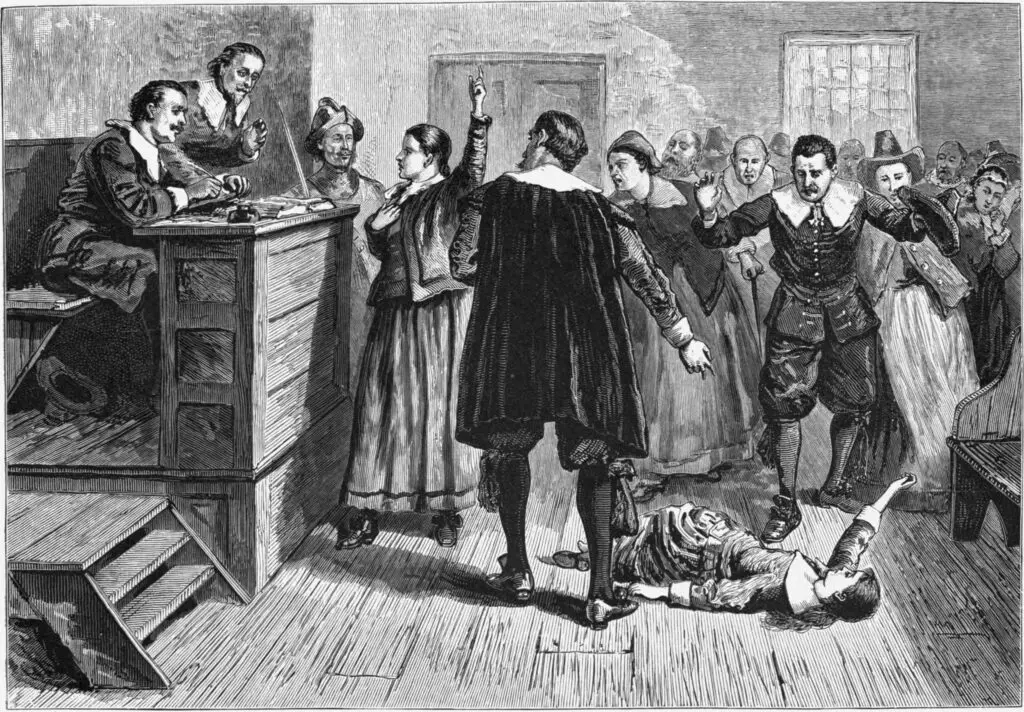

Social justice activism is a religion in that it provides a set of beliefs. These beliefs are to be accepted unquestioningly, and a common language develops between the people involved by which they may identify one another and interrogate and expel heretics.

Pell’s Prison Journal provides an inspiring example of how to endure attacks while loving our persecutors. Perhaps his serene approach can show our post-Christian civilization the beauty of Christian love and forgiveness.

Alain de Botton’s book tells us that we can and should regain hope about the future of our homes and cities. Architecture has been in a sad state in the West for many decades, but there are also glimmers of promise.

Scholdt pays tribute to both the aesthetic achievements and the courage of writers who were persecuted and ostracized during the Nazi era. He also considers the significance of their resistance in the Nazi years for our own tumultuous times.

Through scarcely credible naïveté, Robinson seems to believe that he has disposed of Bryant’s ethical pretensions. His hubris calls to mind those self-destructive British Labour parliamentarians who elicited the jibe that, when granted a choice of weapons, they always selected boomerangs.

Nothing seems wrong with a discerning use of Netflix. But the company’s final goals, Chanot wishes to remind us, are anything but harmless and are bound to destroy the virtues we care to preserve within our families.

The film does a manful job depicting conditions from which few people escape alive, and no soul remains unscarred.

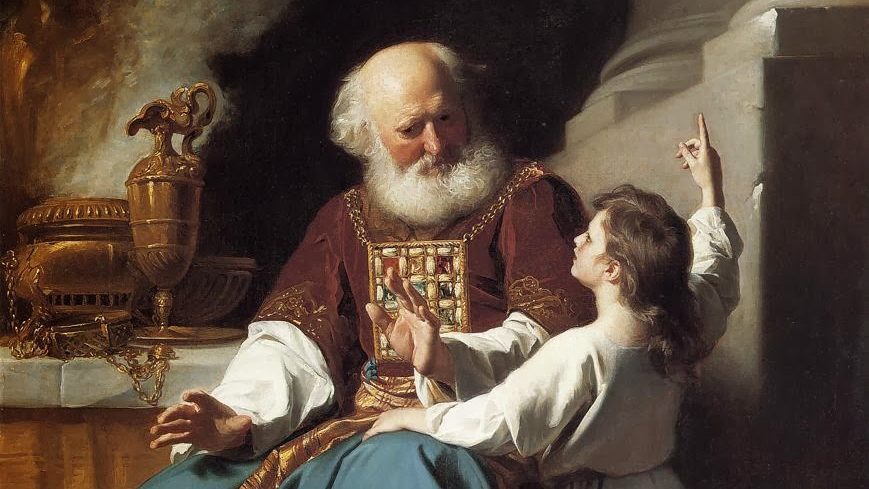

Christ’s parables, such as “The Laborers in the Vineyard,” “The Sower,” and “The Hidden Treasure” serve as a basis for Fr. Sirico’s advice on investing, enterprise, and the value of hard work.

Lewis wants his readers to re-examine our presumptions about everything from modern education and science to ‘the West’ and contraception. Recognizing this can help us understand why the novel has so divided readers.

Isabel Leonard’s portrayal of Carmen was commendably human in a world that often also demands some kind of ideology to peer out from the character.

The geezer is self-assured because he is humble. He believes in moderation in all aspects of his behaviour without feeling entitled or engaging in excessive introspection.

Director Robert Eggers ventures into the world of Norse legends, blending the borders between myth and meticulously recreated reality. Spoilers ahead!

It is hard to imagine a more complex piece than Korngold’s Violin Concerto. It stands on the cusp of classical music’s transformation from an art form confined to the concert hall, into a multimedia concept.

One figure worthy of rediscovery, especially for those of a conservative or religious inclination, is the French soldier and writer Ernest Psichari who converted during his time as a soldier between 1909 and 1912, in what is today Mauritania.

While I agree with the aims and even admire the methods of the protesters of 2019 to 2020, it is likely that when China does assume full control of the Hong Kong territory, they will have made things worse.

Whereas much science fiction simply sidesteps the theological questions a Christian would raise on discovering rational life on other planets, C.S. Lewis asks us to wrestle with them.

Today, the cultural warfare is nothing if not asymmetric. History and culture are important enough to merit a lively debate, but the one-sided onslaught on everything from Western art to our national heroes, thunders Murray, should not be indulged for a moment longer.

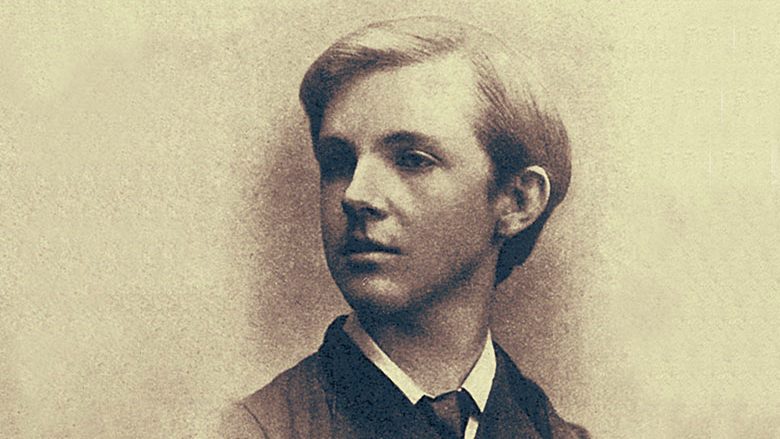

What Lionel Johnson awaited was a biographer who shared both his deep Faith and his soaring erudition in order to convey his work both in its true significance to its author, and on its own terms. With Robert Asch, Johnson has at last found him.

In this massive study, Gregory Collins is able to smoothly blend Burke’s economic thought with his thoughts on politics and human nature.