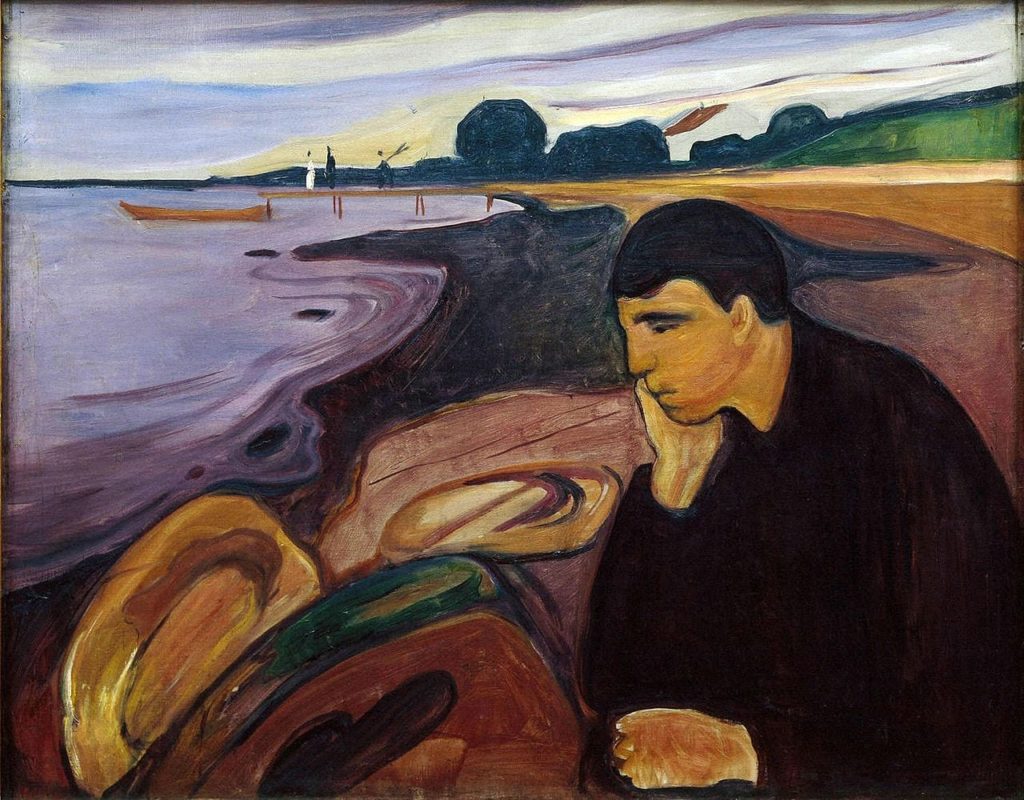

“Melancholy” (1891), a 81 x 100.5 cm oil on canvas by Edvard Munch (1863-1944), one of several variations on the theme painted by the artist during the period 1891-1893. Located in the Bergen Kunstmuseum.

Recently, whilst soaking up the rural idyll of a six-month sojourn in Provence with my wife, I read a forgotten but profound early1962 work by philosopher and psychoanalyst Eugene Gendlin titled Experiencing and the Creation of Meaning. The book is a rigorous and scientific attempt to locate our emotional impulses within the general process of experience—and thereby to expand our grasp of reality beyond what traditional materialistic empiricism allows. While the topic might initially appear arcane, it is extremely helpful for understanding the West’s many grand political blunders of the last twenty years, and it even suggests the beginnings of a possible solution to these errors.

Gendlin divides experience into five broad categories: things said, things thought, things felt, things lived, and the things that fall outside of the first four. Reading this backwards gives us what I believe is the general flow of the transmission of experience from the external world to our interior selves.

According to Gendlin, emotional processes are ontologically prior to rational processes. Look, for example, at the most basic of appetites: the gastrointestinal system. The body needs food, the stomach rumbles, and only then does a thought enter the mind that it would be worthwhile to check the fridge for something to eat. The physical effects of hunger are felt prior to our conscious acknowledgement that we have a problem that needs solving.

It does not take much to realise that the place of feeling in this flow is prior to the place of thought. One important aspect of Gendlin’s account is the idea that something is lost in the process of moving from immediate experience to speech. The author, in one of his most majestic pronouncements, puts it like this: “We think more than we can say, we feel more than we can think, we live more than we can feel, and there is much else besides.”

If Gendlin is right, then, emotion is prior to conscious thought. This means that the current global paradigm—particularly in the West—is wrong. This paradigm consists of a technocratic liberalism for which the only real things are those that can be verbalised and quantified at what, for Gendlin, is the final layer of this flow of experience. This is a fundamental misunderstanding of life and of experience generally, and it seems to me to be at the root of why our world so often appears mechanical and opaque rather than organic and alive.

This seemingly arcane philosophical error is at the root of the series of bad decisions made by politically liberal countries in the twenty years since 9/11. It is at the root of the constant culture wars. It is at the root of the bureaucratic ugliness that filters through all layers of our lives. It is at the root of our belief in graphs and data over the things that we see with our own eyes. By it, we were all perfectly primed to be bamboozled by experts and scientific theory when the COVID-19 crisis reached the shores of the western world in early 2020, a crisis from which we have still to extricate ourselves (and for which we have only suggested technical solutions for escaping).

Emotion in and of itself cannot deliver us from our strange modern situation. Both anti-lockdown marchers and those who support lockdowns at all costs are enacting emotional arguments, and tempers are high on both sides. Emotion was also on both sides of the debates on the Iraq War: well-meaning people emotionally felt that Saddam Hussein was evil and should face the wrath of the free world’s judgement, while millions emotionally marched against any form of intervention. The anti-interventionists have been proven right by history, but at the time there was very little separating the two.

So why mount a defence of emotion? On its own, emotion is not enough to guide us towards the truth. But taking its rightful place in the chain of experience, it is an incredibly valuable resource for understanding our real selves. If Gendlin is right, emotion lies at a much deeper level of our being than our thoughts and certainly at a far deeper level than our explicit speech. If we better understood the fundamental part our emotions play in the daily running of our lives, from our responses to the most important moral dilemmas through to what we choose to eat for dinner, we would begin to understand many things that otherwise appear incomprehensible within the framework of the dominant technocratic and scientific worldview. And by understanding our emotions, we can become more human, more whole, more complete in our understanding of who and what we are and how to live with each other in the world.

Let me give an example. What is the difference between a business report and a poem? Both are mediums of written communication, using the range of vocabulary within their respective language’s framework. I’m unlikely only speaking for myself when I say that business reports cause my eyes to glaze over after the first paragraph whereas poetry—if it is good poetry at least—grips me by my very soul. Why is this? What is happening inside of us that makes Shakespeare more compelling than the NatWest 2021 shareholders report?

The shareholders report is dealing with an abstraction of a technical abstraction; it only engages with the top two layers of our experience, our verbal and thought-based cognitive faculties. Shakespeare, on the other hand, uses language—itself a technical abstraction—to move beyond an exclusive focus on these first two higher cortical functions and to direct its power towards the level of the emotions, a level with a much deeper instantiation of meaning and truth. T.S. Eliot, in his seminal work of literary criticism The Sacred Wood, writes, “Poetry certainly has something to do with morals, and with religion, and even with politics perhaps, though we cannot say what.” The truth of the relationship between poetry and morality, religion, and politics lies beyond language—but not beyond emotions.

The same is true of music and song. There is some suggestion that the first human speech patterns were not made up of functional statements—’Put this here,’ ‘Put that there,’ ‘Enemy over the hill’—but instead group chanting and singing. If so, in prehistory our first verbalisations were at least partially aimed at explaining our interior lives so that others understood. Music and song speak to a deeper layer of ourselves than our thoughts and our speech (it may also be noted that the best orators often are masters of tone, cadence, the silent pause—some of the essential ingredients that also go into making good music).

We have all had the experience of feeling, deep down in our bones, that something is true, but not being able to explain exactly what it is that we feel and what it is that we mean by feeling it. Our emotional self is deeper than and prior to the ‘self’ expressed in the higher cortical functions. When we are afraid, angry, elated, sad, abstract thought slips away to a clearer, more authentic ‘I’ than in periods when we are engaged in the process of thought. If that is true, then thought, as useful and brilliant—even at times sublime—as it can be, represents a shallower layer in the flow of experience than that provided by the immediacy of the emotions.

These emotions that we all possess in some greater or lesser degree are often truer than many of the well-verbalised castles constructed by reason. But the language available to us struggles to cover the range of our interior lives, and so these emotional truths remain ultimately inexpressible.

Interestingly, many ill-meaning people are aware of the primacy of emotion over thought in the way we behave, and they use this to their financial and political advantage. Gambling companies hijack our limbic systems to make us place more bets; social media designs algorithms around our jealousy and lust; and governments engineer our responses to policy proposals through a form of choice architecture—‘nudging,’ as they benignly call it. They attempt to mask what they are doing as appealing to free choice and rationality, but in reality they are playing with a much deeper part of our humanity: one that lies beyond words, and even, in some profound way, beyond reason.

By understanding our emotions as a more primary part of ourselves, we can begin to respond to the deep surging of our emotions as meaningful, and also as something we need not be dominated by. At the same time, we have a chance at last to put an end to the stupidity that has been unleashed by ideologies that function on an emotional level but masquerade as rational. For example, if we can show that patriotism in its unthinking and natural form is truer than any of intellectual sandcastles built either to oppose it or to sanction it into virulent nationalism, we can quickly move beyond from our violently divided politics to another kind altogether: one that validates our emotions and works to put them in an appropriate relationship with rationality. This transition, besides sweeping away a distasteful cottage industry of professional racists and race baiters, would have real-world benefits in the way we relate to each other, both as individuals and as nations. We would be able to develop a much deeper understanding of how patriotism works and how to harness its power for altruistic domestic purposes.

None of this is to take away from the value and power of words and of reason: all great works of literature, all philosophy, all sacred scriptures have been handed down to us in words and (except perhaps the last) are the product of the thoughts and words of particularly excellent human minds. But there is a limit to their capabilities to reveal the full truth about the world and the best way to live in it.

Emotion has a special part to play in how we live, particularly if we want to live well; if we want to understand ourselves and to keep our bearings in the world and our relationship with it (perhaps even our obligations to it). The mind itself is not divorced from this experience of bodily emotion—in fact it is intimately interrelated with it—but there is a part of the brain (conclusively shown by Professor Iain McGilchrist to be the left hemisphere of this bicameral organ) that is unrooted from mere physical reality and tied to abstraction, particularly through language.

Accepting that this is in fact a limiting factor rather than the just arbitration of the truth may help us see where our emotions are more in sync with reality than the technical projections with which we bedazzle ourselves. We may begin to grasp that reality is in fact tied to concepts—so often distorted by acolytes of both right and left—like family, nation, and home, concepts that we respond to with our emotions, first and foremost, which normal people are often belittled for failing to justify intellectually, even though we all know the truth of them in the depths of our hearts.