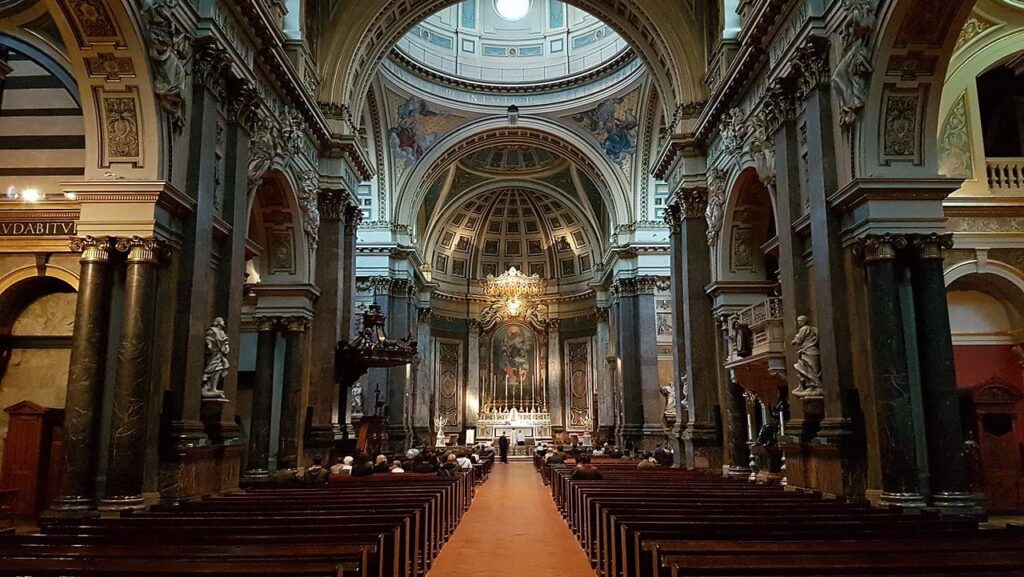

Brompton Oratory, South Kensington, London, UK. Photo by Kleon 3 / CC BY-SA 4.0 Deed

The work of Dalmacio Negro Pavón reveals that politics cannot be understood without anthropology: the various conceptions of humanity throughout history are not mere theories but paradigms that have shaped the lives of peoples and conditioned political thought.

Attempting to expound someone else’s thought is always a high-risk endeavor. But since I recently declared Dalmacio Negro Pavón the most significant political thinker in Spain in recent decades, with all due caution, I will outline what I consider to be some of the interpretive keys to Negro Pavón’s thought.

Last summer, I flew to London in late July to visit two of my grandchildren, as I do twice a year. After awakening on Sunday morning at my favorite hotel in Paddington, I decided, in a burst of summer energy, to strut my way across Hyde Park and attend Mass at the London Oratory on Brompton Road, in South Kensington.

This British Catholic landmark, founded in 1849 by St. John Henry Newman and Frederick Faber, celebrates the Mass in both its modern and “extraordinary” forms. I had been to the Brompton Oratory before but had never attended the Solemn High Mass, celebrated there every Sunday at 11 a.m. I arrived a few minutes early, took a seat near the front, and admired the golden replicas of the menorahs from the temple in Jerusalem located near the communion rail. I wasn’t prepared for what I was about to experience.

It turns out that the Solemn High Mass at the Oratory, complete with a choir singing Gregorian Chant, is celebrated pretty much in the same way John Henry Newman would have offered Mass. I had the odd feeling of traveling back in time—and was astonished at what I saw, heard, and smelled there. Anyone who has attended a Solemn High Mass knows what I’m talking about.

The liturgical experience there is that of a sacred, very intense ritual in which everyone is focused on the high altar and the priestly offering to God unfolding before the congregation, through the consecrated bread and wine that has become the Eucharist and the sacrifice of Christ on the Cross.

Catholics understand the meaning of Christ’s death in a different way from that of many Protestants. Christ didn’t appease an angry deity by suffering in our place the punishment due us for our sins, as Calvin taught. God did not punish Jesus. Rather, Christ’s voluntary act of sacrifice on the Cross was the culmination of an entire life lived in accordance with God’s will. During the Mass, a Catholic priest, acting in the person of Christ, offers to God on our behalf the unique act of self-sacrifice that Jesus endured for our sake and that redeemed mankind and opened up the path of salvation.

As a result, during the Latin Mass every movement of the priest, deacons, and servers is carefully orchestrated, carried out with precision and reverence. There is an overwhelming sense that you really are kneeling in the presence of Almighty God. No one fidgets. During the silent moments, as waves of incense pass over the congregation, you can hear the movements of people sitting a hundred feet away.

I was overwhelmed—and quite shocked at my own reaction. The fact is, I have attended quite a few Latin Masses in the past but this was unlike anything I had experienced before. There was a seriousness of purpose, an intensity, that I had only seen in Orthodox liturgies.

As a cradle Catholic of a certain age, I’ve quite literally spent my entire life living through the debates about the meaning and purpose of Catholic liturgy. When I started Catholic school in first grade, the Mass was still celebrated in Latin. By the time I made my first holy communion, there were already experiments with so-called dialogue Masses (in which the congregation said the responses once said only by the altar servers). My first-grade missal had responses in both Latin and English.

In 1970, when I was 13 and an altar boy myself, the myriad changes that marked the post-conciliar liturgy were already in place. The entire text of the Mass was now in the vernacular, a freestanding altar was placed near the central aisle, the priest faced the people, and the sung Gregorian chant was replaced by the saccharine melodies of the St. Louis Jesuits and Dan Schutte. Yes, I really did sing “Kumbayah, My Lord.”

When I arrived at my Jesuit high school in the 1970s, things got even weirder. The priest in charge of school liturgies was an enthusiastic member of the Charismatic Renewal, a Pentecostal-style movement within the Catholic Church, who regularly spoke in tongues.

I wasn’t bothered by any of this until I got to the Jesuit university I attended. By then, the weirdness of 1970s liturgies had begun to grate on me, even then, and I wrote a series of articles in my school newspaper questioning whether the liturgical reform may have gone too far. Even at 19, I could sense that the Mass of my childhood and the liturgies celebrated in the Jesuit liturgical center were not the same. I did my best to understand what had happened, reading liberal authors such as Tad Guzie and Bernard Cooke and conservative authors such as Louis Boyer, James Hitchcock, and Anne Roche Muggeridge.

In the 1980s, things calmed down a bit. The clown Masses and women ‘priests’ were suppressed, and even the Jesuits were forced to adopt a modicum of dignity. Pope St. John Paul II was a rock star, and it seemed as though everything would turn out okay. As my wife and I were raising five children in the 1990s, parish life rebounded. My affluent parish, having lived through not one but three sexual abuse crises, all involving heterosexual affairs, had the good fortune of getting a magnificent pastor who saw my children through their formative years.

This priest was everything the Vatican II Church had hoped for and promised—charming, funny, a charismatic preacher, a masculine man who rode and repaired motorcycles in his spare time, someone who used to be a football coach and had a natural way with teenagers. He would one day be groomed to be a bishop, only discovering that he disliked administrative work and wanted to return to being a pastor.

Over the years, working as a journalist, I would occasionally write about the dimly remembered Latin Mass of my childhood and the odd groups that continued to insist on its celebration. I wrote about the Society of St. Pius X, the breakaway organization that established its own seminary in Switzerland and ordained its own bishops. But I also investigated and wrote about other, stranger groups, like the one led by Francis Schuckardt of Mount St. Michael’s in Spokane, Washington, a former Jesuit novitiate, and the Society of St. Pius V on Long Island. I spent long hours talking to sedevacantists, people who believe the See of Peter is vacant and the pope a heretic.

I was mostly sympathetic to their liturgical complaints. But the Latin Masses to which they invited me, often celebrated in hotel ballrooms or tiny chapels, didn’t seem like the future. There was something a bit cult-like about the whole thing. Oftentimes the women dressed in Little House on the Prairie dresses, complete with kerchiefs. Plus, as a Catholic I’ve always accepted that it is through the teaching of the bishops in communion with the pope that the authentic faith of the apostles is received—and our bishop (and pope) celebrate Mass facing the people, in the vernacular, handing out communion in the hand.

At the same time, one of my brothers married into a traditionalist family in Wisconsin and kept sending me updates on the TLM (the traditional Latin Mass). I would occasionally attend Latin Masses with him. I was intrigued but not convinced. I knew the Church had lost something, perhaps a lot, in switching from the solemn, reverent Masses of my childhood to what came after. But I hadn’t really realized just how much it had lost, not until I began experiencing the Solemn High Mass at the Oratory—the “whole enchilada,” if you will.

Now, in my older years, I find myself drawn to the traditional Mass precisely to see what I personally have missed out on. (At the Oratory in London, the 11 a.m. Mass is technically the Novus Ordo celebrated in Latin and ad orientem, that is, with the priest facing the tabernacle and the crucifix; the 9 a.m. low Mass, however, is traditional, being celebrated according to the 1962 Missal.)

Naturally, right when I am feeling this pull, Pope Francis, in his wisdom, has decided to stamp it all out by force—rather like the character played by Martin Sheen in the 1973 film adaptation of Brian Moore’s novel, Catholics. In this prescient satire of our times, Sheen plays a modern Catholic priest after “Vatican IV,” someone who meditates in the full lotus position and dresses like a layman in an old Army fatigue jacket. He is sent to an isolated island monastery off the coast of Ireland to demand that the abbot there, played with craggy world weariness by Trevor Howard, cease celebrating the traditional Latin Mass, which is gaining a larger and larger following among ordinary people. Both the film and the book end with the abbot sadly promising to obey the Vatican decree to eliminate the traditional Latin Mass, despite the angry opposition of his brother monks.

The truth is, I long ago gave up following the politics of the liturgy. I find the debates of liturgists tedious in the extreme. As a busy father and now grandfather, I have too much on my plate to read books accusing the architects of the liturgical reforms of being freemasons. All I want is to worship God in peace, with dignity, preferably with the ancient rites of my Catholic ancestors—whom I trace back to defiant recusants in northern Yorkshire. Right now, I attend a very dignified Novus Ordo Sunday Mass at a local basilica, and once a month drive out to a magnificent new monastery that celebrates the Novus Ordo in Latin, facing the people, with incense and chant.

But it’s not quite the same. Experiencing the Solemn High Mass, almost indistinguishable from how it was in its heyday, with the entire congregation holding their breath as the words of consecration were whispered at the high altar, and the priest holding up the host in an offering to God, revealed to me just how much we have lost.

Just when Pope Francis appears determined to suppress forever this ancient rite, which dates back at least 1,500 years, many of us now wonder if it may be the only thing that can restore sanity, and a living awareness of God’s presence, to his foundering Church.