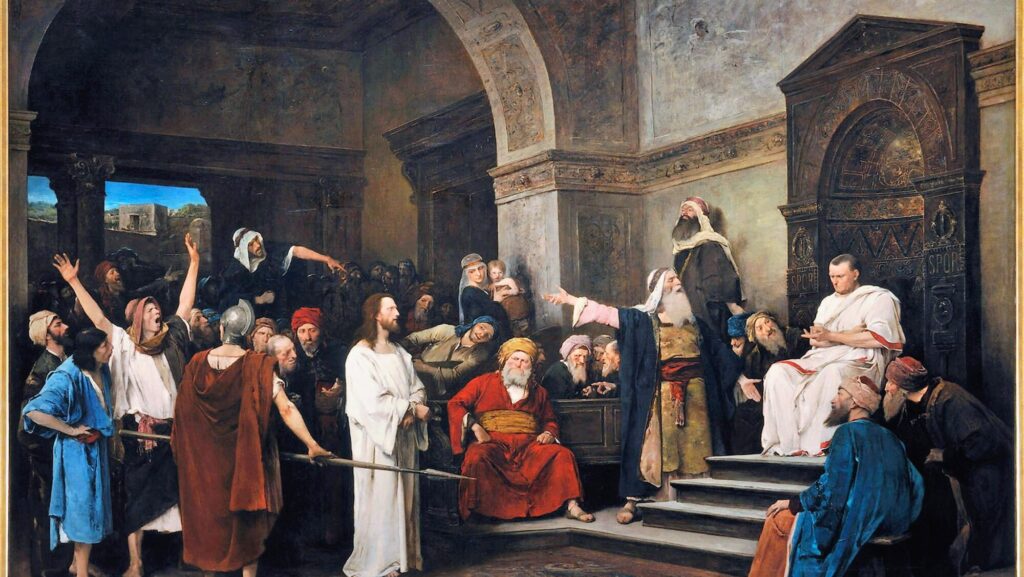

Christ in front of Pilate (1881), a 417 cm x 636 cm oil on canvas by Mihály Munkácsy (1844-1900), located in the Déri Museum in Debrecen, Hungary.

Attempting to expound someone else’s thought is always a high-risk endeavor. But since I recently declared Dalmacio Negro Pavón the most significant political thinker in Spain in recent decades, with all due caution, I will outline what I consider to be some of the interpretive keys to Negro Pavón’s thought.

The work of Dalmacio Negro Pavón reveals that politics cannot be understood without anthropology: the various conceptions of humanity throughout history are not mere theories but paradigms that have shaped the lives of peoples and conditioned political thought.

As the traditions, beliefs, and customs that have upheld our Western societies erode before our very eyes, our pluralist political systems are becoming ever more dysfunctional. Freedom and justice seem ever harder to come by. A dictatorial, intolerant, militantly secularist progressivism forces ever more injustice and unfreedom upon us in manifold spheres of life, disguised behind labels such as ‘social justice’ and ‘the right to choose.’ Words and language are manipulated to distort reality, as in the case of ‘diversity, equity, and inclusion.’ In order to avoid being canceled or shunned, most people feel forced to use these dishonest terms in everyday conversation. Christians, traditionalists, and other people of faith are accused of being bigots because they do not support the delusional ideologies behind identity politics, death with dignity, gender fluidity, and the other novelties of an age in which, in their rage against reality, people live in fictions created according to their own desires.

Not surprisingly, this political and social dysfunction brings with it instability; the two phenomena exacerbate each other in a vicious circle. In the U.S., it is no longer considered rhetorical hyperbole to claim that the survival of American democracy depends on the outcome of Trump v. Biden. In Europe, the political establishment remains stubbornly deaf and dumb amid a rising wave of populism that might well result, sooner or later, in the end of the elites’ ‘European Dream’ of world peace via EU-style supranational governance.

Anger and rancor are rising and show few signs of abating. The criminalization of political differences in our Western democracies is widespread and threatening to become the norm. In the United States and Poland, to name just two examples, political disagreement could lead to imprisonment. In the past few years, left-wing violence and marauding youths have transformed many cities in Europe and the U.S. into lawless no-go zones. Most recently, the vicious hatred and sadistic violence of Hamas on October 7 has elicited rampant antisemitism among wide swaths of our populations rather than support for Israel and the Jewish people. At elite universities in the United States and on the streets of Europe and the U.S., we see lawless protests against Israel and in support of terrorists.

Given all of the above, there are questions that I would like to examine: should we as Christians support pluralism; and why do the great majority of traditionalist Christians still believe in political pluralism? After all, most of the chaos that we are experiencing in our pluralistic societies coincides both with the accelerating loss of the Christian faith in the West and also with the resulting waning of our foundational Judeo-Christian values. It is undeniable that the madness of secularist progressivism has infected all of our political institutions, and that a major reason for this is the absence of a strong and leading religious presence in the public square.

Furthermore, as Christians, we believe in truth, and we believe we know the truth. We believe that this knowledge of the truth saves us and enables us to act with greater wisdom and virtue. In opposition, the commonly heard, thoughtless, and shallow celebration of pluralism for its own sake—the kind of thing we often hear from politicians or read in official declarations—arises instead out of a moral relativism that is ultimately irreconcilable with Christianity. Why should Christians parrot the politically, socially, and culturally correct bromides about the virtues of democracy, diversity, and pluralism, and thereby grant political power to people who are decidedly opposed to the Christian faith? To me, the answer is clear, in spite of all the apparent counterevidence: we Christians must support political pluralism because of our faith and our experience.

Our faith does not teach us that we are better than those who do not share our beliefs. To paraphrase Martin Luther, though we are saints, we remain sinners at the same time. We are not exempt from the corruption, foolishness, and arrogance from which arises the lust for power. In The Gulag Archipelago, the great Christian novelist and social critic Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn wrote that “the line separating good and evil passes not through states, nor between classes, nor between political parties … but right through every human heart—and through all human hearts.” Unrestrained power cannot but have deleterious effects and lead to the abuse of power for selfish ends—usually, for the purpose of maintaining and increasing one’s power over others.

This is true especially for Christians, because in seeking unrestrained earthly power, we are directly disobeying the command of Christ to follow him and to be humble as he is humble. Though an equal with God, he “did not count equality with God a thing to be grasped, but emptied himself, by taking the form of a servant, being born in the likeness of men. And being found in human form, he humbled himself by becoming obedient to the point of death, even death on a cross.”

The Bible is filled with passionate denunciations of the corruption of religious leaders. These were not pagans but leaders who claimed to serve the one true God. Speaking through the Old Testament prophets, God himself cursed the brutal and greedy leaders of his people. For example, God commanded the prophet Ezekiel to announce:

This is what the Sovereign Lord says: Woe to you shepherds of Israel who only take care of yourselves! Should not shepherds take care of the flock? You eat the curds, clothe yourselves with the wool and slaughter the choice animals, but you do not take care of the flock. You have not strengthened the weak or healed the sick or bound up the injured. You have not brought back the strays or searched for the lost. You have ruled them harshly and brutally.

In the New Testament, Jesus spent his entire ministry bewailing the hypocrisy of power-hungry religious leaders. In the Gospel of Matthew, he cries out:

Woe to you, teachers of the law and Pharisees, you hypocrites! You are like whitewashed tombs, which look beautiful on the outside but on the inside are full of the bones of the dead and everything unclean. In the same way, on the outside you appear to people as righteous but on the inside you are full of hypocrisy and wickedness.

Similar imprecations are found throughout the Bible, from Genesis to Revelation. The fact that Christians are not called to exercise unrestrained power is also borne out by history. Think, for example, of the situation in medieval Europe when the West thought of itself as Christendom—the Christian world with Church and State both claiming loyalty to the one true God. Throughout the more than 600 pages of A Distant Mirror, her history of the 14th century in Europe, Barbara Tuchman argues that society failed to live up to its Christian ideals:

The gap between medieval Christianity’s ruling principle and everyday life is the great pitfall of the Middle Ages. … Chivalry, the dominant political idea of the [Christian] ruling class … left as great a gap between idea and practice as religion. … [Members of the ruling class] were supposed … to serve as defenders of the Faith, upholders of justice, champions of the oppressed. In practice, they were themselves the oppressors.

A few centuries later, Christendom imploded in the religio-political cataclysm of the Protestant Reformation. It is a widespread myth that the Reformation was principally about doctrine. As much as or more than doctrine, the Reformation was about the greed and the political and spiritual abuses of a church corrupted by unrestrained power. Luther’s treatise of 1520, An Open Letter to the Christian Nobility of the German Nation Concerning the Reform of the Christian Estate was a call for the secular powers to assert their authority over the church in order to curb the abuses of church authorities who claimed unlimited power for themselves.

After the Reformation, the Protestants committed major abuses of power in their own right. Luther was a virulent antisemite, urging in On the Jews and Their Lies that Jewish synagogues and schools be set on fire, that safe conduct on highways be denied to the Jews, and that cash, silver, and gold be taken from them. Thomas Müntzer, a Reformer far more radical than Luther, urged the peasants to engage in the bloody German Peasants’ War of 1525. He believed the uprising would usher in a new age—the advent of the apocalypse, in which God would correct all the evil in the world. He arrogated to himself the status of God’s servant against the godless, thereby playing a lead role in a revolt that resulted in the deaths of thousands of peasants.

In recent decades up to the present day, scandals of abuse in the church have again proliferated. For decades, there were many cases in many countries in which Catholic clergy committed abuse against innocent parishioners. Often, church authorities, rather than seeking justice, engaged in cover-ups. Reports of widespread abuse in the Southern Baptist Convention, the largest Protestant denomination in the United States, revealed years of cover-ups in a culture that protected the powerful at the expense of the weak and vulnerable.

One of the biggest current sensations in American Christian circles is Michael J. Kruger’s Bully Pulpit: Confronting the Problem of Spiritual Abuse in the Church (2022). The book describes the devastating effects of spiritual abuse by pastors and other church leaders, abuse that generally goes unopposed by elders or others called to hold corrupt leaders accountable. In fact, often those who come forward are treated in ways chillingly reminiscent of how corrupt governments treat whistleblowers. Church authorities tend toward the same circle-the-wagons mentality as secular political leaders. In order to realize the overriding objective of protecting the institution, church leaders often discredit or even destroy those who come forward. This all has to do with power: Kruger defines spiritual abuse as occurring when a religious leader wields “his position of spiritual authority in such a way that he manipulates, domineers, bullies, and intimidates those under him as a means of maintaining his own power and control, even if he is convinced he is seeking biblical and kingdom-related goals.” The book resonated with Christian readers because so many Christians have experienced this kind of behavior.

Clearly, Christians, just like all other human beings, remain subject to pride, lust for power, and abuse of authority. Even in today’s dire circumstances, we are not to aspire to unrestrained political power or, indeed, to the abolition of pluralism and the revival of a ‘Christian’ state. To paraphrase the great Christian martyr Dietrich Bonhoeffer, our ultimate loyalty belongs to God, not to political power. In seeking to gain unrestrained political power, we put ourselves in grave danger of lording it over others and thereby rejecting Christ and his example of humility. And, as so many Christians who have succumbed to the siren song of power have done in the past, we would rationalize our actions by distorting the faith we claim to believe in.

A final word: Christians should, of course, not be reluctant to serve as unapologetically Christian voices in the public square. We Christians should engage politically out of our Christian faith. We should firmly oppose the evil being done by secularist progressivism and fight for a society deeply influenced by the truths of the Christian faith. But we must do so with personal humility and with a healthy awareness of the limits—and the limited importance—of politics. Furthermore, we must take to heart the dignity of all persons, regardless of their beliefs, as God’s image-bearers. We must pair that with a sober recognition of our own weaknesses, flaws, and tendency toward corruption, regardless of our beliefs. We are in a dire situation in the post-Christian West. Let us remember that we have been put in this situation not to seek power, but to serve God and our fellow man. And to do so with profound and genuine humility.